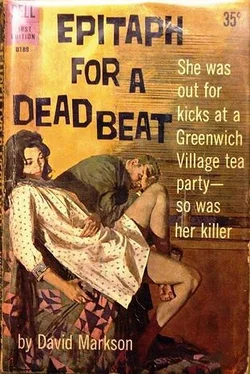

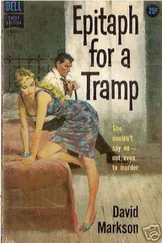

David Markson

Epitaph For A Dead Beat

“They are very Christlike.”

Jack Kerouac

“They are scum”

Somerset Maugham

It is a small, not quite square office behind a smaller reception room on the fourth floor of a Paleozoic brick building on Lexington Avenue. Most of the furnishings have been out of style since Lucky Strikes were green, and in professions where they rate you by such things even the dullest girl in the typing pool would pick a more likely doorway to straighten her seams in. But it contains, such as they are, the tools of my trade as a private cop, and I have been spending the better part of five days a week in the place for seven years.

Probably it is a trivial complaint, but I will always have to wonder why nobody ever seems to need my services until I am out of there for the night.

So I was home undressed when the telephone rang, of course. It was after eleven, and I’d been reading on the couch. Lolita, a sad story about a twelve-year-old girl who couldn’t find anyone her own age to play with.

“—This is Mrs. Skelly. Is this Mr. Fannin? The detective?”

A stranger. Not young, not wealthy, not educated. Probably gray and tarnished, and wearing something cut from shapeless cotton she would call a house dress. There would be a cameo pin.

“This is Harry Fannin.”

“Mr. Lubitch said to call you — the lawyer. You’ll have to bring a gun. It’s about my uncle. There’s so much cash, you see, and—”

“You want me to shoot your uncle for some cash?”

“I beg your—”

There was a pause. “You said there was something Ben Lubitch thought I might be able to help you with, ma’am?”

“Well—”

“I do have a gun — and proper permits. If you need one at this hour I suppose it’s got to do with something you want guarded. Until the banks open?”

“Well, yes, as a matter of fact. It’s Mr. Casey, who just passed on. The poor man was eighty-one, with the railroad for forty-four years. Mr. Lubitch says he’s sure it will all come to us.”

“You’ve found money?”

“In coffee cans, in the closet. Almost four thousand dollars. Mr. Lubitch says you charge sixty dollars a day, but it will be worth it to ease my mind. Especially since he said you would come home and sleep with me, and—”

“Madame?”

“What? Well, really, I certainly didn’t mean—”

“Any old soft chair will do fine, Mrs. Skelly. If you’ll tell me where you are—”

She told me. Grudgingly, but it was me or Jesse James. He’d obviously had an eye on those coffee cans for weeks.

I could have been more enthusiastic. I also could have stopped dreaming that the midnight disturbance, just once, would be a cry of distress from Ava, from Lauren, even from Tallulah. The place was about as far west as you can go in Greenwich Village without driving off a pier, and I said it would take me thirty minutes to get there.

I had to park a block away, on Hudson Street. The building wasn’t quite yet a tenement, although they were already getting interesting effects from the lobby. It was part tile, part chewing gum. The apartment I wanted was 6-B and there wasn’t any elevator.

I made six, puffing, then saw the envelope tacked into the door frame from the length of a dismal corridor away. I put the paper currency into my pocket and scowled at the penciled note:

Dear Mr. Fannin:

I forgot about the police station around the corner. Thank youforyourtrouble,butthemansaidIcouldleavethemoneyin the safe. If you guarded it until 9:30 A.M. that would be tenhours, which is $6 per hour. This $3 is for the time you saidit would take to get here.

Yours truly (Mrs.)

Kate Skelly

PS. Really it would only be 9 A.M. since I would go to the bank as soon as they opened.

I had a smoke before I went down. I wondered if she expected me to leave her a receipt.

It was a nice night, warm for September. On other streets the gears of giant trucks were grinding mournfully, suffering their own version of life’s small abuses, and back on Hudson I patted the Chevy on a fender in sympathy. Fifty yards away a sign which was not entirely unfamiliar said Vinnie’s Place, Beer on Tap, in buzzing red neon. I tried, but I couldn’t think of anyone who would be waiting up for me with a candle in the window. I went in.

It was a mistake, although I could not have known that then. All I had in mind were a few inconsequential drinks.

I thought I could afford it. I’d just picked up all that easy money.

Vinnie’s was a bleak, untinseled cavern about as long as a throw from first base to third, with a bar at the left hand wall and six or seven tables at the right. It had been a sensible longshoreman’s hangout in its day, but since the war the bohemians had been driving out the laboring folk. They had even made something of a shrine out of it, which can happen in the Village. Someone like Edith Sitwell stops a cab one night and trots inside to visit the ladies’ room, and for some people the world is never the same again.

Ten or a dozen stags were scattered along the rail, most of them dressed as if the Kon-Tiki had just discharged passengers at the curb. I found a slot near the back, wondering why my barber hadn’t heard about the strike. Next to me a tall redhead was talking intently to another man I could not see.

“—So like the cat was my best friend, you know? So he sacks out on the sofa for two weeks, and then I can see my wife is giving him the burning glance. So I move out, you know? As long as the cat doesn’t swipe any of my books when he heads back to Frisco—”

“—Touching, man. Like brotherhood.”

A handsome tanned athlete in an open blue button-down set aside a fishing lure with all the care of a museum director situating a mobile, then asked me what it would be. I told him Old Crow and he had to move a paperback called The Way Some People Die to get at the bottle. That made two of us who didn’t belong. I swung around and leaned on one forearm, to get a look at the only girl in there.

She was worth looking at. She was a blonde, with high cheekbones and a delicate face that would not have been out of place on Harper’s Bazaar. It would not have been a calamity on Playboy either, since there was nothing high-fashion about the rest of her. She was wearing jeans and a man’s faded denim work shirt, and after the third button the shirt fell like the sheer drop off a precipice.

She was at a table with two men. One of the men was very young. He had on a tweed jacket with leather patches at the elbows, and he was toying with an unlit pipe. The other one’s back was to me. That one had the same patches on the sleeves of his black turtleneck sweater, and a spiral notebook was jutting out from the hip pocket of his Levis. I got the impression that neither of them would have been chagrined if I got the impression they were writers.

One of them said something and the girl laughed. It was a soft rich furry laugh, like cashmere, and it was wasted in September. In January you could have wrapped it around yourself to keep warm in. Some guy probably did. It made me sad, because the girl reminded me of someone I had been in love with once who died, named Carole Lombard.

I kept staring at her, being ridiculous. She was drinking beer from a bottle, lifting her head and tilting her chair against the wall as a man might. The way she did it would have made it acceptable at a D.A.R. meeting.

She was still sitting back, holding the bottle between her lifted knees, when the front door slammed inward against a table with a sound like a gunshot.

Читать дальше