“Maybe, but I don’t think they liked him.”

“It’s probably better that way,” the lawyer said, heading into the bathroom to brush his teeth. He had known all along that the assistant professor at the teachers’ college would not be the one to find Tarik a bride. He knew Tarik well, and he knew that he was in a tight spot as an Arab-Israeli bachelor in Jerusalem, where there were few matches to be found for those no longer in school, and Tarik had been out of school for five years. Nor was he in the habit of frequenting the humanities department cafeteria, as the lawyer’s wife had advised. Which all explained why, when the lawyer saw that three of the best candidates for the internship in his office were female, he had immediately hoped they were pretty and decided that he’d hire the one who seemed most suitable for Tarik.

“Are you coming to bed?” his wife asked as he left the bathroom. The lawyer was expecting the question, even though he was hoping, on account of his exhaustion and the book that awaited him downstairs, that he would be given an exemption. But it had been two weeks since they’d been together, and the wine she’d drunk during dinner was surely having its effect.

The lawyer shut the bedroom door, fearing that their daughter would wake up and stumble in, and then slid under the covers beside his wife. He knew that she was embarrassed about her body and that even on the hottest summer nights she preferred to conceal it beneath the blankets. They kissed quickly and without passion, and the lawyer set himself to the task at hand.

It would be wrong to say that the lawyer did not enjoy sex, but there was something about it that always bothered him. He found the whole thing to be more of a burden than a pleasure, a situation he knew to be perverse.

He recalled the early days after their marriage, during their honeymoon. He had been twenty-five but it was the first time he had come into physical contact with a woman. He remembered the feeling of shame at the speed with which it had all happened. He knew that something was wrong, and that his wife had not been fully satisfied. She never mentioned it, never said a word about it, but he knew that this was not how it was supposed to be. He remembered his apprehension at the time, the articles he had combed through, the sex-advice columns. After thoroughly researching the matter of premature ejaculation, he had tried to put the techniques to use, relaxing his muscles, pulling his testicles back, dulling his senses with alcohol, even smoking marijuana before coming to bed, but none of it helped. In some articles it said that sexual partners had to learn one another, give their bodies time to get acquainted, to achieve a natural harmony, but the lawyer blamed himself. After a few months of failed attempts, he tried to increase his endurance by summoning sad images from his youth. This worked, and he could tell by his wife’s moaning that some progress had been made. It didn’t happen all at once but he felt, at last, that he was moving in the right direction.

The first time he was sure that his wife had been fully satisfied was after he had screened the footage of his grandfather’s funeral in his mind. The lawyer was eight years old when he saw his grandfather’s dead body. Years later, he lay on top of his wife, thrusting gently, eyes wide open, trying not to be distracted by the sounds of her pleasure. He recalled how the entire family had shown up at his parents’ house and how the body had arrived on the back of an orange pickup truck. He recalled how he had stood off to the side while the adults washed his grandfather’s corpse, which lay prone on an elevated wooden plank. He thought about the prayers the sheikh had intoned and the way the men had shaved the pallid body. And he remembered his grandfather’s wrinkled, flaccid penis and the white sheets with which the men wrapped him as they called out “Allahu Akbar.” He saw himself running in order to keep up with the brisk pace of the funeral procession, saw them raise the coffin up in the air, saw the opening on one side and the way it was tilted down till his grandfather’s white-robed body slid into the grave. He recalled the sound the body had made upon impact, and realized that he had just given his wife her first orgasm. She clawed his back and planted warm kisses on his face while he remained above the grave, aware that he would never again be the boy he had been.

LETTER

In his office, the lawyer found a pack of cigarettes. He lit one just as the baby began to wail. His wife’s measured steps moved toward the crib. The crying subsided. He took a few long drags, then ground the cigarette out in the ashtray and, after a moment’s hesitation, poured water over the blackened stub. Satisfied that no gust of wind would come through the open window and breathe life into the dead ashes, he took a long gulp of water, picked up The Kreutzer Sonata, and left the room.

The lawyer didn’t like getting out of bed once he was settled for the night, which was why he went to the bathroom even though he didn’t have to, and tried, without success, to urinate. Then he went to his daughter’s room, stacked two pillows up against the headboard, turned on the pink bunny lamp, and lay down in her bed, cradling the book.

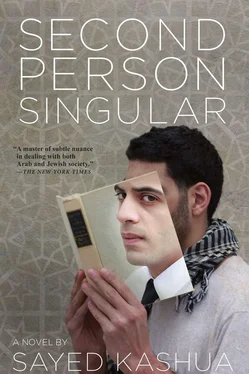

Although it was a used copy and had likely been passed from hand to hand, the book was in good condition, practically new. This, the lawyer felt, spoke to the character of its previous owners. Clearly they valued it, protected it. The lawyer also knew how to care for a book. He never dog-eared a page, never wrote in the margins, never broke the spine. He looked at the rather ugly cover. Two thick black lines dissected it into three unequal parts. The uppermost part was yellow and bore the author’s name, Tolstoy. The lower, green section was home to the title, The Kreutzer Sonata, and the middle one featured an ugly pastel illustration. On the right side of the drawing there was a man with fiery eyes, a hooked nose, and a set mouth. His hand was balled around the handle of a dagger. On the other side of the drawing was a faceless woman whose body was curled and indistinct, her hand feebly raised before the murderer. Had he not known who the author was, the lawyer thought to himself, he would never have bought this book.

He flipped to the front page, where the author’s full name was written, Leo Nikolayevich Tolstoy. He went over the name several times, embarrassed that he hadn’t known it, imagining himself as a contestant on a game show, “What are the first and middle names of the famous Russian author Tolstoy?”

On the contents page, he was pleasantly surprised to find that the book consisted of four stories and not just one, as the cover seemed to imply. Other than the first story, “The Kreutzer Sonata,” there was also “The Devil,” “The Forged Coupon,” and “After the Ball.” The lawyer had an aversion to long books, both because he didn’t have time and because he liked to check off the boxes on the long list of books he felt he should read.

In the upper left corner of the page he saw the name Yonatan, delicately printed in blue ink. The previous owner’s handwriting gave the lawyer pause. Many used books had someone’s name printed on the inside flap but for some reason this name, or rather this man’s handwriting, soft and feminine, begging for help, almost like the cowering woman on the cover, caught his attention. Never mind, he said to himself, start reading. He knew he didn’t have much time. The guests had kept him up late and the wine was taking its toll.

The lawyer read the quote on the first page of the book. “But I say unto you, That whosoever looketh on a woman to lust after her hath committed adultery with her already in his heart.” (Matthew 5:28) He chuckled to himself. If that was the case, he was the undisputed king of adulterers, even though he hadn’t had sex with anyone besides the woman whose bed he had just left. The quote took him elsewhere. He hadn’t even started to read the book and already he found himself transported. He was back in the café on King George Street, reviewing all the women he had seen — young, old, secular, religious, Ashkenazi, Sephardic, Arab, and Jewish. He recalled how he had looked the women up and down, the ones coming toward him, the ones beside him, and the ones in front of him, how he had sized up their behinds, evaluated them in pants and in skirts, how he had examined their thighs, imagined their precise shape, and how he had known that no one was onto him, that he was not the kind of person who got caught ogling — he was quick about it, and yet none of the details evaded him. In a few split seconds he could attain all of the pertinent information. His eyes were trained to spot cleavage, panty lines, bra straps. He registered the way they walked, the way they moved their bottoms, the size and sway of their breasts. The lawyer had no intention of acting on this information. More than anything else, he was trying to figure out his own taste. He knew that his wife, widely considered to be a good-looking woman, did not attract him the way he would have liked, and this he attributed to the shape of her body, her stout thighs, and the stretch marks along her abdomen, which had appeared once their son was born. At times the lawyer felt he was attracted to all women aside from the one he was married to. And at times, while walking behind a woman on King George Street, watching her and lusting for her, he realized that her body was remarkably similar to his wife’s.

Читать дальше