The lawyer shook his head free of these thoughts. He tried to go back to the book, but knew that his eyes would not stay open for more than a few minutes. No sense in starting, he decided. He was too tired. It would be better to begin reading the next day. Before turning off the light, he checked to see how long the title story was. He flipped through the pages, taking pleasure in the gentle breeze and the familiar scent they produced. He reached page 102, where the story ended, and just as he was about to shut the book a small white note fell from the pages. The lawyer started to smile as he read the note, written in his wife’s hand, in Arabic. I waited for you, but you didn’t come. I hope everything’s all right. I wanted to thank you for last night. It was wonderful. Call me tomorrow?

KNIFE

The lawyer leaped out of his daughter’s bed to kill his wife. He’d stab the bitch, cut her throat, gouge out her eyes, butcher her body. Or maybe he’d strangle her. He’d sit on her stomach, straddle her, pin her to the bed, and wrap his fingers around her throat, thumbs pushing deep into the flesh. He saw her writhing, gasping, her eyes popping out of her head, and saw himself staring at her, meeting her pleading and fear with furious derision. He’d throttle her while she tried to resist him, her fingers scratching at his arms as he clamped down on her windpipe, squeezing even harder, puncturing the skin of her neck, soaking his fingers with her blood, keeping up the pressure long after her body had gone slack.

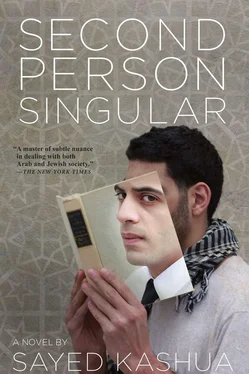

He bounded up the stairs. A fog moved through his mind. He saw an image of his wife, stark naked, laughing uproariously beside a strange, faceless man — a lowlife, the lawyer was sure, a petty criminal, perhaps the man on the cover of the book, the one with the dagger. In his mind’s eye, he saw her as he had never seen her before, moaning, kneading her own suddenly shapely thighs, clinging to the stranger, who lay on top of her, his face filled with scorn and malicious mirth, maybe it was someone he knew after all. His wife’s eyes shone with a passion he had never seen, scratching the man’s back with nails she didn’t have and whispering words of love as she arched up toward him.

The lawyer felt like he was choking. Pain ripped through his head. His heart thumped. His breath was short. Quick. He could not draw enough air. He’d kill her. He’d wake her up without saying a word and he’d kill her, or maybe he’d wake her up, tell her that he knew everything, and then kill her. He turned toward the kitchen, opened a drawer, and looked for the right knife. He grabbed the biggest one, wrapped his right hand around the handle, and headed for the bedroom.

His wife lay on her stomach, a thin summer blanket covering one leg, the other stretched diagonally across the length of the bed, completely bare. She looked at ease, her breathing rhythmic and calm. She was wearing green panties and a simple white tank top. Her face was turned to the right, covered by her hair, which fell across her ear and cheek. This was not the woman he wanted to murder. This was a different woman, one who had a one-year-old baby by her side.

The lawyer’s muscles relaxed. The hand that wielded the knife fell to his side, his head slumped forward, and he began to sob softly at the foot of the bed, realizing that his wife would not have dared were she not so certain of his cowardice.

He moved the pillow that his wife had placed alongside the baby. He’d told her a thousand times to stop doing that. The pillow would not stop the baby from falling out of bed if he rolled over in his sleep. On ordinary nights, when the lawyer woke up in a terror and raced to see that his children were safe, he would pick the baby up and carry him over to his crib, but on this night he was scared of rousing him. He placed another pillow on the floor, where he imagined his son’s head might strike if he fell out of bed. Then he tucked his son back in. His son? A flash of pain surged through his chest.

What would he do now? Wake her quietly so that the baby would stay asleep and tell her to come downstairs, where he’d confront her with the note? Shove it in her face and demand an explanation? What would he do if she said the handwriting wasn’t hers? And maybe she’d be right, maybe it really wasn’t. The lawyer tried to cling to his former life. Of course it was her hand that had written the note. He knew it was. And anyway, what was he expecting, that his wife, who up until a few minutes ago had seemed faithful, almost foolishly so, would just burst into tears and come clean? After all, he reminded himself, he had no idea who she really was. They’d been living together for years and only now did he realize that he did not know her. What if she did admit her guilt? Would she cry, accept responsibility, beg for her life? Promise that she’d melt away without so much as a single demand? The whore.

And what would he do? The coward. The despicable coward. If only he could do the deed. But what about the kids? He couldn’t live with the notion that his kids would see their mother’s lifeless body sprawled before them. He’d get them out of the house. He’d kill her when they were away. Then he’d call the police. And what about him? What would he do? Sit in jail? Commit suicide? He should have killed her right away. He should have done it before he started thinking. But how would he do it? And what about the kids? They’d grow up with no mother and a father behind bars, living with his parents, maybe hers? Oh, God, what had she done?

No matter what, he’d be the laughingstock of his peers and his village. Even if he killed her. He winced at the thought of being ridiculed behind his back. He imagined his friends, including the ones who had been over for dinner, smirking at him, the fancy lawyer laid low. He saw the man to whom his wife had written the note, imagined him sitting with his buddies and regaling them with the tales. Oh, God, what had she done? The bitch. She’d trampled him. Made him a character in one of those stories he was constantly hearing from his clients, about naive husbands who let their wives run rampant. Again he saw clusters of men convulsing with laughter. The lowlife that his wife had taken to bed was sitting with his buddies and telling, precisely, what she had been like, detailing all the things she had done to him, things that far exceeded what the lawyer had thought his wife was capable. It was clear that the fornicator did not hold his newest conquest in high esteem. Or did he? Maybe they were in love? Maybe they planned to live together? How old was the guy anyway? Did he know him? And how long had this been going on?

The lawyer left the bedroom. Once a coward, always a coward he thought. He put the knife back in the kitchen drawer and went to his daughter. She’d tossed off her blanket but he didn’t cover her. It wasn’t cold. It was hot. Stifling. Sweat beaded up over his body.

He went downstairs, looked for the note in the bed, and didn’t find it. He searched furiously through the folds in the blanket. For a second he entertained the notion that he had been mistaken, that he had imagined the whole thing, that fatigue had authored the note. He flipped through the book again, thinking that perhaps he had tucked it back where he had found it, but it wasn’t there.

Then he saw it beside the bed. He picked it up, wedged it deep inside the pages of the book, and took the evidence to his study. He eased the door closed behind him, lit a cigarette, and tried to organize his thoughts. He took a long drag, then exhaled slowly. He might be a coward, but a chump was something he had never been. And he definitely did not plan on being her chump. Who the hell did she think she was? He didn’t even know her. That had to be the basis of his plan, that he did not know her. In the end he would kill her, that much was clear. Maybe not with his own hands, because he had no intention of paying the price for her crimes, but he would bring about her death, of that there was no doubt. At the end of the day, the husband was not responsible for the wife’s honor. Her family members—father, brothers, cousins — were the keepers of the family’s honor; it was their blood, and it was on them alone that the dishonor would rest if they did not take it upon themselves to obliterate it. Not on him, not by any means.

Читать дальше