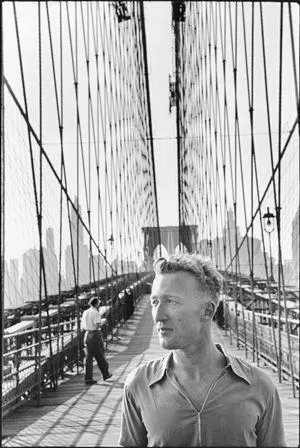

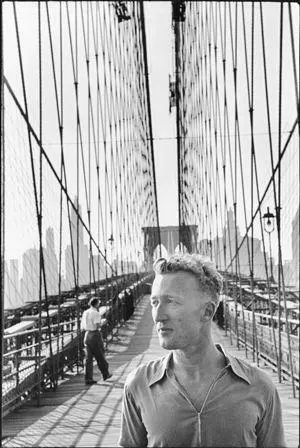

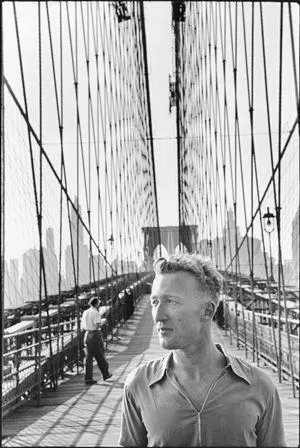

Although I knew it wouldn’t last, as I walked back to Brooklyn from Alena’s apartment across the Manhattan Bridge, everything my eye alighted on seemed totaled in the best sense: complete in extent or degree; absolute; unqualified; whole. It was still fully afternoon, but it felt like magic hour, when light appears immanent to the lit. Whenever I walked across the Manhattan Bridge, I remembered myself as having crossed the Brooklyn Bridge. This is because you can see the latter from the former, and because the latter is more beautiful. I looked back over my shoulder at lower Manhattan and saw the gleaming, rippled steel of the new Frank Gehry building, saw it as a standing wave; I looked down at the water to see a small boat slowly pass; the craquelure of its wake merged with the clouds reflected there and I briefly saw the vessel as a plane. But by the time I arrived in Brooklyn to meet Alex, I was starting to misremember crossing in the third person, as if I had somehow watched myself walking beneath the Brooklyn Bridge’s Aeolian cables.

Our world

The world to come

I wandered on Henry Street through Brooklyn Heights. Alex and I were meeting for a drink at a place just across Atlantic, although Alex wasn’t drinking. She had started a new job for which she was radically overqualified and underpaid; she was basically tutoring kids at an after-school program in Carroll Gardens, but she felt it would be best to apply for other jobs while employed and she wanted the structure and welcomed whatever money. I ordered something with bourbon and mint and a sparkling water for Alex and took our drinks to one of the wooden booths. The carefully selected ephemera on the walls dated from before the Civil War; there seemed to be a competition among hip bars to see who could travel back in time the furthest. We sipped our drinks under Edison bulb sconces.

“Are we going to talk about your very clumsy effort to seduce me?” I’d written Alex an e-mail about my semen analysis but we hadn’t really talked about my trying to do it all. She wanted us to go in and talk to the fertility specialist in detail about the results.

“I was amazed you could resist my charms — I even recited poetry.”

“I’m serious.”

“It was stupid and I’m sorry. I was, as you know, very drunk.”

“That was the problem. That’s what you should be sorry for.”

“Okay. But why?”

“Because if we’re going to try to make a baby, however we try to make one, I don’t want it to be one of the things you get to deny you wanted or deny ever happened.”

“What do you mean?”

“‘It was the only kind of first date he could bring himself to go on, the kind you could deny after the fact had been a date at all.’”

“That’s fiction and we’re not talking about a first date.”

“What about the part about smoothing my hair in the cab? The part that’s based on the night of the storm. The alcohol is a way of hedging. So that whatever happens only kind of happened.” I made myself not take a drink.

“Okay, but your whole plan only kind of involves me — my level of involvement to be determined, whether I’m a donor or a father. You’re asking me to be a flickering presence. I give reproductive cells and then the rest we figure out as we go along.”

“Yes, but that’s because it’s up to you. As I’ve said since the beginning, if you want to fully coparent, whatever that would mean, I would do that with you. I wouldn’t have asked you otherwise. I would prefer to do that with you, in fact. If you want to try to have sex as part of a reproduction strategy”—I involuntarily raised my eyebrows at the phrase “reproduction strategy”—“or whatever you want to call it, I’m open to that, too. We’d have to talk more about it. You would have to stop sleeping with Alena, at least during that time. That would be too strange.”

I drained my glass. “What, we’d be a couple? Are you proposing?”

“No. People do this. It would be like we were … amicably divorced.” We both laughed. We had no idea how it would work. But I knew how we could pay for it: I told her I’d sent off the proposal, described my plan to expand the story.

She was quiet for half a minute, then: “I don’t know.” I’d expected her to say it sounded brilliant, which was what she normally said whenever I ran a literary idea by her — an adjective she’d never applied to any of my nonliterary ideas.

“What don’t you know?”

“I don’t want what we’re doing to just end up as notes for a novel.”

“Nobody is going to give me strong six figures for a poem.”

“Especially a novel about deception. And it sounds morbid to me. I feel like you don’t need to write about falsifying the past. You should be finding a way to inhabit the present.” I remembered the sensation in my chest when I’d sent off the proposal, as if that way of dilating the story was linked to the dilation of my aorta. “And anyway, you shouldn’t be writing about medical stuff.”

“Why?”

“Because you believe, even though you’ll deny it, that writing has some kind of magical power. And you’re probably crazy enough to make your fiction come true somehow.”

“I don’t believe that.”

“How often have you worried you have a brain tumor?”

“Not once,” I laughed, lying.

“Liar. Remember what happened with your novel and your mom.”

In my novel the protagonist tells people his mother is dead, when she’s alive and well. Halfway through writing the book, my mom was diagnosed with breast cancer and I felt, however insanely, that the novel was in part responsible, that having even a fictionalized version of myself producing bad karma around parental health was in some unspecifiable way to blame for the diagnosis. I stopped work on the novel and was resolved to trash it until my mom — who was doing perfectly well after a mastectomy and who, thankfully, hadn’t had to do chemo — convinced me over the course of a couple of months to finish the book.

“Do you know what I realized the other day,” I said, “while being interviewed by somebody from the Netherlands over Skype about that novel, which just came out in Dutch? I realized how the lie about his mom is really about my dad.”

“How?”

“Or about my dad’s mother, my grandma, whom I never met; she died when he was twenty. I don’t know if you want to hear a story about mothers and cancer right now.”

“I would like to hear the story.”

“My dad told me all of this when I flew home from Providence for Daniel’s funeral my freshman year of college. He picked me up at the airport and we started driving back to Topeka and I was so upset I could barely speak. I remember we were moving slowly because there was a light but freezing rain. The first part of the story I’d already heard: the day his mother died from breast cancer—‘cancer’ was never said in the family, but everybody knew, even the kids — he called up his girlfriend, Rachel, who was soon to become his first wife, a marriage that lasted all of a year, and before he could say anything, he realized that she was crying and that he could hear weeping, no, wailing in the background. Before he could share the news about his own mom, before he could even ask what happened, Rachel said: My father died. Rachel’s father, a well-known businessman in D.C., where my dad lived and was now in college, had been perfectly healthy, as far as anybody knew. But on the same morning my dad’s mom died after a multiyear struggle with a terrible illness, he just dropped dead at his office from a coronary.”

Читать дальше