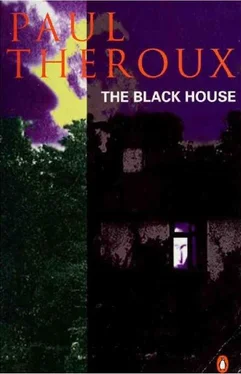

Paul Theroux - The Black House

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Paul Theroux - The Black House» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1996, Издательство: Penguin Books, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Black House

- Автор:

- Издательство:Penguin Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1996

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Black House: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Black House»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Black House — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Black House», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

It gave him a bad dream, of a tall house on a black landscape where the wind had flattened the meadows and the gates in the hedgerows were broken. He was walking towards the house, slowly in the yielding grass, his feet sinking with each step; and up close he saw it was a stone house, like his own, with a black slate roof, but (and this woke him) it had no doors or windows.

7

It came to him, what she had said on their first day at The Yew Tree; he forgot what preceded it or prompted it, but her words “You know nothing” had swiped at him. And he remembered how he had changed the subject, heading her off with, “What do you mean by saying I’m ridiculous?”

He was not defeated then, he knew how she exaggerated, and he did the same—the precise managing of exaggeration, on which was pinned a timid sincerity, was a convention of their marriage. They didn’t say what they meant, but this manner suggested all that was unsaid. It was an English trait which Africa had intensified almost to the point of parody. They had met by chance, and almost resenting the love they called a deep sympathy so as not to feel foolish, they had married late—Munday was forty, Emma two years older (she had money: it had made her shy, nearly kept her single)—so Africa, which Munday studied and Emma endured, was their honeymoon. Their African isolation had thrown them together, like new cellmates who, once solitaries, learn in a confinement where they are robbed of privacy to protect themselves from greater violation. They had come to each other with a single similarity, a perverse kind of courage each saw in the other but not in himself. That, and an irrational thing—though at the time it seemed like conclusive proof of a common vision—their discovery one evening in idle talk of a fascination they shared for that polished Aztec skull of rock crystal in the Ethnography Section of the British Museum. “There’s only one thing in the world I care about,” Emma had said. Munday had almost scoffed, but when she disclosed it he was won over and from that moment he loved her. They had seen it as schoolchildren and returned to it as adults. It hadn’t been moved; it was still in the center of the aisle, in the high glass case, mounted on blue velvet. It was like an image of their common faith, the carved block of crystal in the dustiest room of the museum, the cold beauty of the blue shafts, sparkling behind the square teeth in the density of that death’s head. Emma said that she had whispered to it—Munday didn’t ask what—and that it was so perfect it made her want to cry. Munday said it was the highest art of an advanced people and he told Emma its cultural origins; but he venerated it no less than she.

Later, married and in Africa, they discovered how opposed they were, but this opposition, their differences with their determined sympathy, gave a soundness to their marriage. Munday had a vulgar streak that Emma’s primness sustained and even encouraged. Munday blustered and was rash; in a professional argument with a younger colleague he would tab his finger intimidatingly at the man and say, “I won’t wear it.” Anyone interested in his work he saw as a poacher. His colleagues said he was impossible and shortly he had no colleagues. He had a reputation for arrogance, and very early in his career he had learned an elderly trick of blustering, pressing his lips together and blowing out his cheeks and prefacing an outrageous remark with something offensive, “Damn it, are you too stupid to see—” Marriage only made his anger blind: he had Emma, and if he went too far he did so because he knew how his wife could draw him back. He might rage, but it was her sensibility that he trusted, not his own. He protested loudly but secretly he believed in her strength, and that belief in her timely sarcasm gave him strength. He relied on her in all ways, to pay for his research when his grant was exhausted, to support his temper and defend his opinions. His science he knew was opinion, full of guesses that made him sound crankish, and she mocked him for it. But just as often-and with more sincerity she reassured him. She allowed him to make all the decisions and complained so haplessly her complaints amounted to very little. But this was insignificant to what bound them, for though in conversation he exaggerated his strength and she her weakness, he knew—and the knowledge gnawed at his confidence—how he leaned on her. So many times in those past days he had tried to reveal his fear to her! Emma, gentle, knew at what moment his pride would allow him to be reassured by hen But they had said nothing and now it was too late. She had seen what he loathed and dreaded, she had named his fear, and in that naming, locating the woman at the window, she had dismissed all her strength. Her picture of the fear was his, she had described his mind. Munday was stripped of his defenses; he was alone; there was no one to turn to.

Without knowing it she had defeated him by confirming his fear, and for the first time she was relying on the strength of his doubt, on his assurance that they were quite safe. Munday had repeated what she asked him to, but he had no answer to console her. He had no answer to console himself. He was staggered by the weight of his own and his wife’s fears. He worried about himself; poor health was his egotism: he saw himself collapsing, falling forward dead in the darkest room of the black house. That star of pain which had twinkled on and off now burned ceaselessly like a hot knuckle of decay in the pulp of his heart. His sleep was a kind of stumbling at night, going down in a restless doze and then scrambling to consciousness. Usually he lay awake, rigid in his bed, listening to the slow clock and the ping of the electric fire, his eyes wide open, wanting to wake his wife and talk to her. He envied her slumbering there, her body purring with snores, but he could not divulge his worry and he knew that to tell her his fears would be to have her awake beside him, fretting through the night.

One night, early in December, he slid out of bed to go downstairs for some aspirin. He made no sound. At the bedroom door he heard:

“Where are you going?” Her voice was sharp; its alert panic implored him. It was not the monotone of a person just awakened—it had the resigned clarity of his own when he said he’d be right back. He said nothing more; he imagined that their exchange had been overheard, and when he returned to the bed and Emma embraced him, pulling her nightgown to her waist and fingering his inner thigh, he drew away, whispered “No,” and immediately looked around half-expecting to see a witness, staring in a blue and gray dress.

In the daytime he was tense with fatigue, and though he did not sleep much in his bed he dozed in his chair, nodded over his food, and sometimes out walking he felt he could not go one step further: he wanted to drop to his knees and fall down in the sunlight on a grassy knoll and sleep and sleep. His mind spun, stampeding his thoughts, and his arms and eyes were heavy and wouldn’t work. So the preparation of his lecture took as long as if he was doing a paper for a learned society. He hated every moment of it, making notes, putting his colored slides and tapes in order and labeling the tools and weapons he planned to pass around to the audience.

After lunch, on the day he was due to give his lecture at the church hall, Emma said, “Let’s get some fresh air.”

It was cold and windy and very bright, typical of the weather in its new phase. There were slivers of ice in the stone birdbath that lay in the shadow of the house. They climbed the bank in the back garden and stood in the humming gorse and broom at the edge of the high meadow. Beneath them was the vast green Vale of Marshwood, sunlit and so deep they could take in most of it at a glance, the several village clusters—each marked by smoking chimneys and a square church steeple topped by a glinting gold weathercock—the dark measured hedgerows, the nibbling sheep like rugs of spring snow on the hillsides, the scattered herds of cows, and here and there small wooded areas, islands anchored in the rolling seas of the meadows. Wide gloomy patches of cloud shadow, the shape and speed of devil-fish, glided across the floor of the valley, rippling over trees, swept up the slope, and passed over the Mundays, blocking the sun and putting a chill on them. They continued to look, not humbled by the size, but triumphant; at their vantage point on its very edge, where it began to roll down, they had an easy mastery of it, like people before a contour map on a table. Each house and bam and church was toy-sized and the whole was marred only by the file of tall gray pylons and their spans of underslung wires across the southern end of the valley. At the sea was a ridge of hills, gold and green downs which opened where the low late-autumn sun dazzled on the water. That was as far as they could see. Closer, just under them, blue smoke swirled over a terrace of thatched cottages; a dog barked, three yaps, and there was a tractor whine, a laborious noise drifting up from where the vehicle was turning, at the border of a brown oval of earth in a large field. Miles away there was a short flash, the sun catching a shiny object; they saw the flash but not the man who held it. Around them were their trees, beech and oak, the ones that moaned at night and sang in the day; their limbs were bare, the leaves that had not been knocked off by the rain had been tom off by the gusts of wind. There was no mistaking them for African trees, which were only bare in swampland; these were stripped, and as tall and dark as a row of black-armed gallows.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Black House»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Black House» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Black House» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.