By June Audrey’s found her buyer. She’s ready to go, but where? He says, “Well, we’ve both got some money.”

She says, “Are you serious? I mean is this us talking serious?”

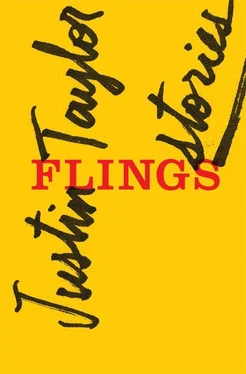

He says, “I moved to this shit-ass city to become a rock star. Instead I’m an office drone and, increasingly, a raving Communist, only the only times I have time to rave I’m too drunk or too sleepy and the people who need raving at aren’t around, or they are but they’re holding my leash. Sometimes when I can’t sleep I search Craigslist for sublets in Canadian cities. Square footage alone has brought me to the verge of weeping joy.” This is the longest monologue he’s ever taken in her company. She throws her arms around his wide neck, tilts her pelvis into his hip.

“I want a new guitar,” he says. “Acoustic.”

Part of the deal for the Grind Shack is Audrey has to help the new owner learn the ropes, so Gregory’s alone in Montreal the first few weeks of July. When they Skype he plunks out “Love Minus Zero/No Limit” and can see her in her little digital box, melting for him. And there he is, in his even smaller box inset in the corner of her box, the Ibanez slung across his belly, his sweaty head agleam. Sometimes they let whole minutes pass in silence; he watches her and he watches himself watching her. Audrey in her New York living room, a pale face afloat before a plain gray wall. He takes epic walks around Montreal, up backstreets, down alleys, wherever. If a parade went by he’d probably join it. In a bar near McGill he finds himself knocking back whiskies with a guy who does research on sleep cycles. Guy’s going on about fruit flies, the never-ending bitchwork of grant proposals, how it’s gonna be when he gets his degree, his own lab, tenure. Guy says he wants to move to New York City. There’s a postdoc at Columbia he’s got an eye on. Gregory starts to tell him about the old loathed Bed-Stuy share, the way the city stinks in summer. Guy’s not saying much anymore and Gregory, worried his frankness has unnerved, swerves toward a different subject.

“Dylan?” says the guy. “Yeah, he’s okay, sure, but what about Albert Ayler, Funkadelic, any Dead show from the spring of ’74?” Gregory, swaying on his barstool and feeling osmotic, scribbles names and dates on a napkin, offers to get the next round.

The day Audrey’s train comes in it starts pouring, doesn’t stop for two weeks. They have no idea how to live in a house together. They don’t even know where the nearest grocery store is. He’s been on an all-takeout diet, trying to figure out whether it’s (1) possible and (2) worth it to jam out “China Cat Sunflower” on solo acoustic guitar.

“This isn’t working,” Audrey says, staring forlorn out their front window at the gray rain veiling the world. Looks back over her shoulder, sees the look on his face, clarifies that she meant Montreal. “Or maybe Canada altogether. We need to get back to the roots of things. Where did you grow up?”

“Indianapolis.”

“Okay, forget your roots. What would you say to a cabin in the pines outside of Johnson City?”

Gregory says he’s always wanted to explore sweet Dixie. Audrey’s sundress makes a blue pool at her feet.

But August is a stupid time to be anywhere. That’s what he keeps telling himself to feel better about being here. The cabin has front and back porches he can stand on in the shameless nude. Not bad. But it’s forty-five minutes to the nearest strip mall full of chain stores and the rednecks they encounter on their weekly supply trips do not charm him. His faith in Žižek wavers. He thinks the Slovenian has given short shrift to Buddhism; he’d like to investigate for himself but doesn’t know where to start. He and Audrey can go a day, days, without speaking, to each other or at all. He can lie down on the floor and listen to Albert Ayler’s Live in Greenwich Village from start to finish without feeling the least bit restless or opening his eyes even once. Are these things Zen? And if not then what is fucking Zen? Bodies moving past each other through the same hot rooms, pouring cold drinks into jelly jars, throwing steaks in the skillet, flat on their backs in a queen bed, side by side. Sounds all right when you put it that way, but still, something’s off.

At the back of the bedroom closet he finds an old math textbook left behind by some former occupant’s no doubt underachieving son. He decides Algebra II must be like Buddhism and suggests to Audrey that they seek to master that which they faked their way through in the prehistoric and halcyon days of their respective tenth grades. They work in earnest on problem sets, sneaking glances across the raw scored kitchen table, then check each other’s answers. The work gives their lives a grammar and their days a shape. By September they’ve completed chapter ten, running way ahead of the schedule suggested by the book, though as far as the book knows they are (1) fifteen years old, and (2) taking five other classes besides this one, plus presumably extracurriculars. Audrey says she tried track but wasn’t built for it. Ditto honor society, A/V club, chess club, and debate. Gregory played football, had a nickname and everything, until a senior year knee injury reduced him to recording secretary for the local student chapter of the Young Republicans. Their biggest accomplishment had been remembering to show up on Yearbook Picture Day. Three of the six with clip-on ties. Now he’s holed up in the woods with this woman, wearing pilled boxers, torn undershirt, unending beard — all three of these articles dried stiff with his own sweat plus Audrey’s, having finally mastered that bitch goddess the quadratic equation, and it’s like, Who the hell was Jacques Lacan, where the hell on the map is Slovenia, and how could I have ever fallen for this lisping poseur’s bad voodoo?

Audrey says her rank-choice vote for the next city is Austin, Texas; Portland, Oregon; Madison, Wisconsin; Portland, Maine. He says, “Baby, when I look in the cracked mirror of this cabin’s bathroom what I see is a man who is in the place that is the right place for him.”

“’Cause you stopped shaving your head,” she says, “or grooming your beard. Your mountain man fantasy’s about a half inch deep; see if there are some scissors around we can restore your dignity with — my Lady Bic if it comes to that.”

“How will a Lady Bic restore my dignity?”

The night she leaves they have one of those legendary sessions, personal instant classic, a story you’d tell to everyone you knew if you knew how to say it in a way that didn’t make you sound retarded: it was exactly the same as always but somehow infinitely better, the best. Then she gets dressed, puts her things in the car, goes, is gone. When her taillights wink out of view he strips down, stands stark on the porch in the crisp October air. It’ll be a long walk whenever I leave here, he thinks, and he’d like to write a song about the feeling of that knowledge, an expressive instrumental composition, something soulful and crisp with a touch of melancholy, a kind of bright-eyed fatalism, like John Fahey on Of Rivers and Religion or Nathan Salsburg on Affirmed . Instead he uses GarageBand to record a twenty-six-minute “Not Fade Away”  “Uncle John’s Band”

“Uncle John’s Band”  “Goin’ Down the Road Feeling Bad”

“Goin’ Down the Road Feeling Bad”  reprise of “Not Fade Away.” He adds layers of himself doing the harmonies and backups, foot stomps and handclaps, beating forks against the math book and the table and the skillet for a little drum break, emails the result to his brother as the first sunbeams cut through the pines. His brother writes back an hour later: “If you need a place to crash you can say so.”

reprise of “Not Fade Away.” He adds layers of himself doing the harmonies and backups, foot stomps and handclaps, beating forks against the math book and the table and the skillet for a little drum break, emails the result to his brother as the first sunbeams cut through the pines. His brother writes back an hour later: “If you need a place to crash you can say so.”

Читать дальше

“Uncle John’s Band”

“Uncle John’s Band”