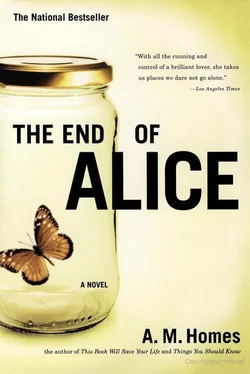

A. Homes - The End of Alice

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «A. Homes - The End of Alice» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1997, Издательство: Scribner, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The End of Alice

- Автор:

- Издательство:Scribner

- Жанр:

- Год:1997

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The End of Alice: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The End of Alice»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

a novel that is part romance, part horror story, at once unnerving and seductive.

The End of Alice — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The End of Alice», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I am at the center of you.

Flick my thumb against the hidden hood, the most tender morsel in its overcoat. I push back that skin, letting out the little lump, my clam, oysterette, what women call their little prick. I suck that snail, eat escargot. Breath escapes you with your cum. You cum and I do not stop, I go on knowing what comes next, the best is after last, there is always more — always something interesting just the other side of pain.

I kiss. Having always wanted to make out with these sacred spots, I brush your lips with my own, blow you with my breath. I kiss so softly you don’t know I’m there. Lip to lip. I kiss this second mouth, part it with my tongue, toothless shark, lots of layers folding and un, becoming quite like tiny tongues. I speak into you, saying things I cannot tell you to your face.

Curl my lip, roll it back, and expose my teeth; fuck you with my face, scraping the liquid of your ecstasy, scraping until your flesh is weak, until you break and begin to bleed. And then I suck that blood, drink you down.

And saving the best for last, I pull out the most favored toy, my precious BB gun — a long-dead father’s gift to his only son. I travel with it tucked inside my bag and rarely use it, but today is special because I’m here with you. So I unpack the would-be rifle, pump it up three times, and put it to you. I blast you once and you buck a bit; the second time you seem still surprised as though no one had ever thought of such a thing. I stroke the barrel and am filled with memories; screaming squirrels, broken bottles, bull’s-eye pucks in widows’ windows. The black paint is chipping. Again, I pull the trigger and then withdraw, leaving you with my ball bearings buried in your walls. You look so perplexed. Oyster, don’t you get it? In your shell I have put three grains of sand. Make me a pearl!

TWELVE

Random swearing in the hall. Things overheard.

“Walk me down. Walk me down. Why my woman always walk me down? Bitch, whore, fucking cunt. Why you look at me like that? Oh, the humanity. What for lunch?”

“You can’t run and you can’t hide, where you gonna go, death row? Ha, ha, ha, ha.”

Prison. Bells. Fourth of July. The pyrotechnic plot. Rumor swirls, the rooster crows, something is up, word is passed down, around, we are due for a visitation; a reward or a shakedown? Nervous with anticipation, the men surreptitiously do a late-spring cleaning, disposing of all illicit stock. When the rising timbre, the tidal wave’s roar, the fiery flush of industrial-strength toilets becomes so violent, so self-determined as to threaten the septic system, an investigation is instigated. The men, well rehearsed, claim the culprit is something served for dinner the night before, if not the fish sticks, then the tartar sauce. The doctor — the man of my so recent acquaintance — is called, and we are ordered to bare our butts, bend over at the cell door and let his proxy’s latex fingers slip us bullets to bind. But as soon as they are gone, the tiny torpedoes of Compazine are fired out the ass, medicating only the toilet water. You can lock us up, but you can’t keep us down.

Due to the overload, the water is shut off for several hours. At 4 P.M. we are given the word that despite the surprising epidemic of gastrointestinal upset, our nearly riot level of anxious activity, despite the stoned and sedated state of those men who were not quick enough to squirt their suppositories — the evening’s events will go on.

In a grand gesture of community relations, of seemingly selfless sacrifice, the denizens of the town nearby have switched the site of their planned pyrotechnics so that we might passively participate. This year they will fire their fanfare due south so that we behind the walls might have something to see. Snacks will be served. Attendance is required.

Eight P.M. Out of our cages and into the hallway. Men hesitant to leave the luxury of home are pulled from their cells by guards in riot gear. We are handcuffed and hobbled, arms and legs joined in giant ropes of chain. Twelve men form a line. The guards, even though they’re getting time and a half for holiday service, aren’t happy. Scared shitless is more like it — they’ve never taken us out at night. Like a conga line we move through the maze, threading through the tunnels and traps, the same old hallways painted battleship gray. With the chink-a-chink-a rhythm of so much chain, the tragic dance of the bound and tied, the shimmying shake of a tambourine, jingle bells, we wind down and around. Right to left, side to side, whatever you do you do it together, in concert with the man in front of you. The extension of the chain is short, and in order not to be pulled and pained, one has to learn the way. Penguins hop. Synchronous swimmers. June Taylor dancers. Slithering snake. We wrap around the yard and are positioned, stretched out in even lines.

“Sit,” the guard before us barks. And we do, lowering ourselves to the ground. It is a herky-jerky thing.

“They’re treating us like dogs, animals, put out for the night,” Kleinman says, scratching himself.

The high carbon arcs of the towers cast a glow over the yard. Bright white. Light, so much light. An opera, a grand opening eve. Ushers-cum-guards work their flashlights like lasers, leading prisoners to their seats. The far stone walls have become a backdrop to the most classical of stage sets — we are the theater.

Through a broken bullhorn, the majordomo addresses us. Only bits and pieces are audible. His cracked address sounds something like this:

“Grateful to the town of ale firing jerks in our face, spiritual if and Owen Overstern, fucking flasher, for aching this onerous gift, the ax you are about to receive, eat candy, men, dentist month. Annoy! Annoy!”

Razor wire glitters, glinting like something hungry. I wonder what else it’s caught besides Jerusalem’s flesh and the occasional cat who gets its furry throat slit while the bird it chased takes off — the revenge of flight.

“Treats, treats, pass us some sweets,” Frazier begins the chant.

Volunteers, graduate students in criminology, work their way up and down the rows, passing out the party favors, big boxes of Cracker Jacks, past their expiration date, all of them opened and with the prizes removed.

The lights go off. We are dropped into darkness. There is a steaming hiss, the sudden suck of breath. A hush sweeps the crowd.

It’s been more than two decades since I’ve seen the night. The sky hangs like a velvet curtain. I stare at the stars, picking out Polaris, — the Big and Little Dippers, and Cassiopeia, the queen. I offer them the simpleton’s prayer, “Star light, star bright, first star I see tonight, wish I may, wish I might, get the wish I wish tonight.”

In the distance there is a dull thud. We sit in our stone cage, black box, blind and dumb. A few flashlights play over the crowd. The curtain lifts, the first one clears the wall, a fine white burst exploding into a thousand stars. I try quickly naming them before they disappear: Alice and Amy, Barbara and Betty, Cathy and Caroline.

Boom. Boom. Boom. Bombardiers. Chrysanthemums of light.

Sparkles fall like fairy dust and I am doused in memory. Fourth of July: I set a hundred sparklers in my grandmother’s yard — spend the early evening pushing them down into the grass — and when darkness falls, I call my grandmother onto the porch and race to light them one by one, firing them like the magical spill of a domino line.

“Don’t use all my Blue Diamonds or you’ll be down to fetch me matches come morning,” my grandmother shouts. “I’m using punk,” I call back. “Only punk.”

“That’s right, you’re a punk. Glad you know it.”

“Scorched,” she says the next morning. “You burned my grass, that was good zoysia I had there.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The End of Alice»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The End of Alice» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The End of Alice» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.