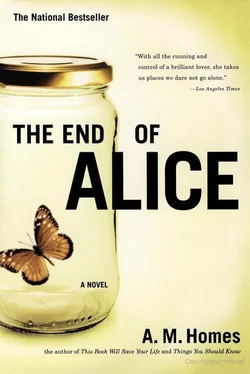

A. Homes - The End of Alice

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «A. Homes - The End of Alice» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1997, Издательство: Scribner, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The End of Alice

- Автор:

- Издательство:Scribner

- Жанр:

- Год:1997

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The End of Alice: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The End of Alice»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

a novel that is part romance, part horror story, at once unnerving and seductive.

The End of Alice — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The End of Alice», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

They wave her away and race down the street. It is early evening, not yet twilight; the sky is a deep blue, the air holding the heat of the afternoon. The ice cream truck is ahead of them. They run, overcome with apprehension, the fear that the truck will drive off before they arrive— they’ve seen it happen before. Just as they come upon it, the driver lets out the brake and rolls away, a-jingle. And the fact is, the drivers do it on purpose, especially where fat little kiddies are concerned. As the chubby child nears, the truck pulls a few hundred feet farther down the street and pauses. As the hefty hefalump again closes in, the truck eases another two to three hundred feet down the road— a teasing tug-of-war repeated several times before the driver grows bored, pulling away entirely, causing tubby to turn homeward, to deepen his depression. Or the driver, if given to a kind of sadomasochistic sympathy, will tease and taunt and then stop, ultimately letting the obese infant have his reward, figuring to have made him work for it, to have made the ice cream better than good, a treat actually earned.

Like precocious playmates, proper pals, our girl follows her boy up the sacred staircase to the family’s private quarters. Good Humor in hand, they are temporarily returned to a world of childhood, of make-believe where all is goodness and nice. And in his room, his cramped but special cell, they circle each other, spinning, turning the tension tighter as they struggle to keep a space between them, as they dance in rings around each other, like dogs sniffing.

She is the teacher, he is the pupil. She is the girl, he is the boy. She is older, he is younger. She has the power, he has the power. Neither knows what they are doing. It is a tie, a dead heat; they spin and spin and suck on their melting ice cream sticks. They circle until they slowly settle, until they are dizzy and nauseated from the duck, duck, goosing version of musical chairs, until she is left sitting at his desk and he on his bed, each hiding behind the melting bricks of ice cream that hang precariously off their wooden sticks. He finishes first, leaving a chocolaty ring, an outline and guide around his mouth. Again and again, she wipes at her lips, craving to keep them clean. But it is impossible to stay untouched, untainted, in such a situation, and without noticing she drips onto her shirt.

They look at each other but don’t smile.

His room is like that of any boy, decorated with furniture of his parents’ choosing, augmented with sporting equipment and dirty clothing. On the bedstead is a clock radio, a pile of sticky Popsicle sticks, and a large wad of hardened green gum. Low on the wall, down behind the bed, where no one but an expert, an archaeologist of greatest experience, would think to look, are gray-green smears, chunky crumbles, fragments of discharge, the nose picked and smeared, boogers. His sheets, thoroughly visible due to the unmade nature of the bed, are well-worn, thoroughly loved Batman sheets. For the boy, they are a source of power. Putting him to sleep in this bed is like slipping him into a battery recharger for the night. Head positive, feet negative, and with eight hours of solid charge each night, he glows, positively shines by morning.

What to do? What to do? What do these children do? Talk about? After all, they have never really spoken before. Nothing that one could consider a conversation has passed between them, and now they are alone, like this. What will happen next? My heart races. I am watching with my hands over my eyes. I want to know and yet I don’t want to know. The suspense is killing me. If you haven’t noticed it, you are a fool. This is the beginning, the true start of things, the time when, without speaking, they simultaneously acknowledge the real reason for their meeting. Sometimes you are such a fool that I wonder what you are doing here, playing these pages. Perhaps you would be better off with the World Book, a nice quiet encyclopedia.

“Wanna see my stuff?” he asks.

She nods.

He gets up and moves to whip out his things, his collection of cards — baseball, football, etc. He shows her the cards and talks about how he is a generalist, specializing in nothing, dabbling here and there, sampling this and that, sure that someday, some piece of it will be of enormous value, which piece he can’t quite be sure.

“Know what else I’ve got?” he says, peeling back the closet door, pulling the light chain. “Records. I have all my father’s old records. I’m building a collection. Used to love the Beatles, but now I like Jimi. Jimi Hendrix?” He begins to play air guitar and dance around the room. He comes close to her. She is reeling. He jerks open a desk drawer and flashes a succession of neatly ordered boxes.

“And candy,” he says. “I collect candy. Theme candy. Java Jaws. Pandemonium Puffs. And glasses. I have a small collection of gas-station glasses. They’re downstairs. Every time there’s a new glass, I make my dad fill up or get an oil change, whatever it takes.” He falls silent and rummages through the drawers. There are things from school: ruler, compass, calculator, pencils and pens, metal fragments, pieces of this and that, spare parts.

“There’s another collection, something I make myself,” he says, taking a small white cardboard jewelry box out of the drawer. “Promise not to get grossed out. I mean, I know you will, but like, swear not to hold it against me or anything.”

“I’d never hold anything against you,” she says.

He seems hesitant, suddenly shy.

“I swear.”

Still dubious.

“Show me. I want to see.”

He opens the box, lifts out the cotton, and tilts it in her direction. In the corner she sees a few small raisiny, shrively things.

“Scabs,” he finally says. “I pick my scabs and save them. Dried out they’re crispy, kind of chewy. The flavor changes depending on what generation it is, whether it’s blood-based or peroxide. It’s kind of complicated, a science, knowing how, when to harvest. But they’re good. I pick them, put them in this box, and then every now and then grind one up between my teeth. Am I the strangest guy you ever met?”

She shakes her head. “No, but you’re very sweet.”

The boy looks at her as if she hasn’t heard a word he’s said, as if she’s entirely missed the point. “And you’re cute,” she says. “And I bet you taste great.”

He blushes and starts to rattle his box. “Want one?” She nods. “Fresh,” she says, pointing to his knee.

There is a thick crustation across the mid-kneecap, dark and heavy, close to mature. The edges poke up slightly.

“A little accident on the gravel about a week ago,” he says, flicking it with his fingernail.

She drops to her knees and crawls across the floor toward him, kicking the door closed along the way. He scoots to the edge of the bed. His legs are hanging over. She licks the knee, the scab, to soften it, to wash and ready it. The flavor is a wondrous rich mix of dirt, sweat, and blood. She licks slowly and then, with the long nail of her index finger, pries, peeling the scab up. It comes away slowly, painfully, leaving a pink well that quickly fills with blood. She presses her tongue to the coming blood and draws it away. The well refills and then overflows the wound, running down his leg. She holds the scab to the light of the Luxo lamp on the desk.

“A good one?” she asks.

“The best,” the boy says, still breathless from his surgery.

She slips the scab into her mouth. He shudders. She is eating him. He’s never seen anything like it. His eyes roll up into his head; he falls back onto the bed.

Fainted. Out for the night.

Without a word, with only the smallest smacking sound of her sucking the scab, she goes to his desk, opens his notebook to a blank page, and scrawls, Tomorrow at three, her words going out of the thin blue lines. And then she goes downstairs to the living room, taking care to tuck her treat between cheek and gum so as not to lose it, not to swallow too soon. She stops to thank his mother and father for their hospitality. “Thank you,” she says. “Thank you so much.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The End of Alice»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The End of Alice» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The End of Alice» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.