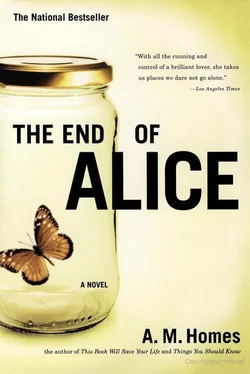

A. Homes - The End of Alice

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «A. Homes - The End of Alice» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1997, Издательство: Scribner, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The End of Alice

- Автор:

- Издательство:Scribner

- Жанр:

- Год:1997

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The End of Alice: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The End of Alice»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

a novel that is part romance, part horror story, at once unnerving and seductive.

The End of Alice — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The End of Alice», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

There’s an odd charge in the air, I felt it right away, but at first thought it was just me. Or us, Clayton and I. Clayton finally responding to my request, my interest in having my cock sucked, me responding to the subsequent image of her sucking my cock with Clayton looking on, her watching Clayton fucking me. No, I don’t want her to see that, don’t want anyone to see Clayton fucking me. Too embarrassing. I fear they would think less of me if they knew what I let Clayton do. I’ve gone too far, trespassed. I backtrack.

In the yard everyone moves with an urgency typically absent. The men on the path are walking as if racing, pumping their arms back and forth through the air, faster, faster. Smokers are smoking, puffing and pulling, blowing billowing clouds of nicotine into the air. Faster. Faster. Time is spinning out of order, calling attention to itself. A guard comes out onto the catwalk, the terrace that surrounds his turret, raises his binoculars to his turd face, and scans the yard. Not yet.

I’m the first to notice. Jerusalem at the wall.

He touches it, puts his hands up against the stones as if he can read them with his fingers, with his eyes closed, in braille. The story of a man. One foot inches up and catches on a stone in the wall, his weight shifts and the second foot leaves the ground. His fingers clutch the edges of the stones, digging into the mortar. He is five feet into the air. In the turd tower a guard pulls the cord and the farting foghorn of a siren begins to bleat. A warning. The walkers, the men on the path, freeze and then begin to dart back and forth, unable to make their rounds, to cross beneath the climbing Jerusalem. Instead — and as though this were the predetermined emergency plan — they go back and forth, up and down, pacing the length of the yard. Jerusalem is shirtless, Wonder-bread white. The flesh on his belly and back wriggles. He struggles to find his footing, get his grip. Twenty feet into the air. Rifle in hand, a guard comes out of the tower and stands on the catwalk, whispering into a walkie-talkie.

Clayton turns to me and says, “Wedding day,” in my ear.

“What?”

“Daughter Debbie’s wedding day. Doesn’t want to be late for church.”

I remember Jerusalem showing me the invitation: The honor of your presence. Deborah, Darling Daughter of Emma and Jerusalem, to Keith Quick. Eighteenth day of June. Christ Church, Poughkeepsie. Reception to follow.

And now Jerusalem is on the wall. The turret terraces are full of guards with their guns drawn. Shoot to kill. They have the authority. The farting horn bleats every thirty seconds. Excruciating. They hold their fire, allowing us the illusion that someone can get up and over. They humiliate us and Jerusalem by letting him play out the fantasy. Their refusal to shoot represents their unwillingness to participate, to even dignify our desire. The pressure is too much, we are being simultaneously scrutinized and ignored. We begin to slowly crack. The men, responding to the intensity of the focus, the sudden flood of chemicals through their delicate systems, develop involuntary spasms, twitches — Jerusalem’s climbing disease. He is on the wall, working his arms and legs like an insect, desperate, trapped. There is a roar, a growing growl, as the energy, the impulse, overwhelms, as the inmates come undone. They howl and bay at the guards, they claw and tear at themselves and each other.

Clayton looks at the guards in the towers, the guns, opens his arms, and holds them above his head. “Ready,” he screams. I step away. “I’m ready now,” he yells. He spins, showing himself to them. “Now would be nice.” He takes off his shirt and bangs against his chest, his heart. “Here. Here would be good.” They ignore him. “Do it,” he screams. “Do it already.” And still there is nothing. “Please,” he begs. “Please, I can’t anymore.” And when the guards continue to ignore the men below, Clayton hurls himself through the air, throwing his body like a punch, landing in the mud puddle from yesterday’s thunderstorm. He hits the muck with a slapping sound. I am embarrassed by his display. I move farther away, toward the door leading back inside. Men cower there. The door is locked. They are keeping us in the yard, in this antique stadium. Jerusalem is ten feet from the top; his breath, the gallop of his heart, plays off the stones, echoing over the yard. He moves carefully. His hand is on top, over the edge. He starts to pull himself up. His legs are pedaling the wall, finding their footing. He leans forward without thinking. I see him do it. I know as he does it, there will be trouble. His shoulder snags on the wire; he turns, twists, and pulls his legs up. His shoulder is in the wire, it digs into him, pulling at his flesh as he moves. He dips down, as if by going lower he will release himself. His face is down. The more he fights, the more tangled he becomes. Wrapped, trapped, buried. He moves as if he’s swimming in place. The guards lower their guns. We are fifty feet down, looking up. Five minutes, ten minutes pass, and the assembly of guards seems to be dissipating as each goes on about his business irrespective of the fact that a man hangs like a piece of laundry.

“Pyramid.” Word sweeps through the yard. “Seven, then six, five, four, three, and two.”

Clayton pulls himself out of the puddle and positions himself on the bottom. The men stack themselves on each other’s shoulders, six men high. The guards return, cocking their rifles. They step into position. Reinforcements magically appear, administration men in dark suits draw their.38s and aim them at the dull spots between our eyes. The two inmates on top wrap wads of shirting around their hands and arms and reach into the wire. They separate Jerusalem from the steel, plucking him out, leaving pieces like samples, small strips of skin set out to cure. His limbs stay bent as they bring him down. They carry him across the yard — his back is the only part uncut. Blood drips from him onto their heads and into their eyes, trickles down to their chins and splashes the ground. They lay him down; Frazier goes first, kicking him hard in the ribs. “Useless,” he screams. “What were you thinking?” Then Wilson hauls off and gets him in the gut. “Idiot.” Embarrassed, humiliated by Jerusalem’s display, Kleinman swings his leg, tapping Jerry under the chin. And Frazier goes again, this time for the groin. “McNuggets.” Clayton kicks him solidly in the back. I am horrified. Jerusalem curls protectively and someone else kicks, and then Frazier is taking another turn and it’s going around again. The guards stand watching, and soon we’re spent, bored. Jerusalem is still. Seeing that we’re done, the guards open the door. Clayton and I are the last ones in the yard; we peel Jerusalem up and drag him to his cell.

Henry comes and pokes the man, checking for broken bones. “Superficial,” Henry says, pressing his ear to the chest, listening for cracks, pops, wheezes. He gives him a shot, a “low dose of my new analgesic,” and leaves.

I lean forward, dipping my tongue into the blood on Jerusalem’s chest. Clayton looks at me. “There’s red on your nose,” he says. “A hint of pink on your cheek.” He smiles, laughs, and licks the blood off my face.

“The flavor of life,” I say.

We lean forward and lick Jerusalem’s wounds, teasing the scraps of flesh with our teeth and our tongues. And as we lick Jerusalem, cleaning and drinking him like crazy cats, he begins to moan. He weeps at the sting of our saliva, the flick of our tongues.

“Jerusalem,” we say.

“It’s a mistake,” he says. “Just call me Jerry.”

Finally the siren stops. The bells ring. Dinner. A second set of bells. Lockdown. Room service. We bid Jerusalem good-night and go back to our cells. We don’t eat. We have already feasted and for now are sated.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The End of Alice»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The End of Alice» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The End of Alice» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.