DAY 11

I have considered feeding myself intravenously but I worry that medical professionals would realize the unique quality of the blockage, and would conspire to take it from me.

DAY 12

Mr. Wallace called today to ask why I haven’t been coming to work. I had been a model employee in terms of attendance and grooming. I wish I could press the appropriate button and confirm that yes , I was feeling fine, that yes , I would like to keep my job, that it would be nice if everyone understood that I was doing something for the benefit of the world and that my duties as a paper-mover would have to wait. The colors in my body have moved and centralized at my throat. There is a terrible pallor in my face and hands but I am heartened by the growing darkness around the strange, wonderful object.

DAY 13

The swirling patterns behind my eyes confirm what I have secretly felt for days, that it is time for the blockage to finally emerge, the gestation period has concluded, the suffering is nearly through (though it has not been true suffering and we will never know true suffering), that which will most closely resemble joy is prepared to leave my body and move into the world!

DAY 14

I am wildly aware of the feel of everyday things. My body feels wholly perishable against the tile and dirt and ground it touches. I set out the silver bowl I once received as a wedding present (so long ago, such strange emotions!) as well as a set of silver spoons and monogrammed hand towels. My plan was to expel the Object into the bowl, but when I attempted the expellation (hunched over the bowl on the floor, which I chose to be the easiest method for both myself and the Object) I was greeted by a sharp, shocking pain. My nose bled into the bowl and I hunched nearly blind with emotion but the blockage screamed OUT and my grasping hands touched bowl, towel and finally spoons! And gratefully I took a spoon in my shaking grip and fully formed ideas flashed before me, Stop the bleeding! Save the Object! And I do understand that this will be a difficult labor, indeed!

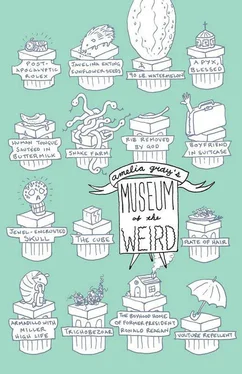

The children who found the cube shrieked over it as children do. The adults couldn’t be pulled away from the picnic at first, and assumed that the children had found a shedded snakeskin or a gopher hole. Only when the Rogers kid touched the iron cube and burned his hand did the parents come running, attracted by the screams.

It was a massive monolith, wider than it was tall and taller than anyone could reach, wavering like an oasis in the heat. The Rogers kid wept bitterly, his hand already swelling with a blister.

Nobody knew what to make of the thing. It was too big to have been carted in on a pickup truck. It would be too large for the open bed of an eighteen-wheeler, and even then there were no tire marks in the area, no damaged vegetation and not even a road nearby wide enough for a load that size. It was as if the block had been cast in its spot and destined to remain. And then there was the issue of the inscription.

They didn’t notice it at first, between the screaming Rogers kid, his mother’s wailing panic to hustle him back to camp for ice, and the pandemonium of parents finding their own children and clasping them to their chests and lifting them up at once. The object in question itself received little scrutiny. Only when the mothers walked their children back to camp for calamine lotion and jelly beans did the rest of the adults notice the printed text, sized no larger than a half inch, on the shady side of the block:

EVERYTHING MUST EVENTUALLY SINK.

The words caused an uncomfortable stir among the gathered crowd.

“What about Noah’s Ark?” asked one man in the silence. “After the flood, the ark was lost in the sand.”

“What about buoys?”

“Given time and water retention,” said a woman who worked in a laboratory, “a buoy will sink like the rest.”

This was disconcerting news. Everyone stood around a while, thinking.

“What about an indestructable balloon?”

“Such a contraption does not exist, and is therefore not a thing.” “A floating bird, such as a swan?”

“It will die and then sink,” the first man said, annoyed.

One man made to rest against the iron cube and stepped back, grimacing in pain at the surface heat.

“A glass bubble, then.”

The laboratory woman shook her head. “The glass would eventually erode, as would polymer, plastic, wood, and ceramic. We are talking thousands of years, but of course it would happen.”

The group was becoming visibly nervous. One young man recalled a flood in his hometown that brought all the watertight caskets bobbing out of the earth, rising triumphantly out of the water like breeching whales. The water eventually found its way though the leak-proof seals and the caskets sank again.

Another man recalled a mother from the city who drove her car into a pond, her children still strapped to their seats.

A man and a woman walked to camp and returned shortly with a cooler of beer. The gathered crowd commenced to drinking, forming a half-circle around the cube. They agreed that many things would eventually sink:

A credit card

A potato (peeled)

A baby stroller

A canoe

A pickle jar full of helium

A rattan deck chair

A mattress made of NASA foam

They even agreed on alternate theories: everything that sunk could rise again, for example. One of the men splashed a few ounces of beer on the iron surface as a gesture of respect. The place where the beer touched cooled down and the man leaned on the cube. It didn’t budge.

The men and women grew drunk and their claims more grandiose (a skyscraper, an orchard, a city of mermaids). Eventually, the mothers came to lead them back to camp but they didn’t want to go, eliciting words from the mothers, who had been stuck with the children and each other all afternoon and were ready for the silence of their respective cars. Back at camp, they were throwing leftover food into the pond. Ducks paddled up to eat the bread crumbs and slices of meat and the children clapped. The Rogers kid stayed on his mother’s lap, picking jelly beans from her hand. A pair of siblings threw an entire loaf of bread into the water and watched it disappear.

The mothers didn’t talk much, preoccupied with children or ducks. As they sat, some thought about the children, and some thought about everything eventually sinking, but most thought of the long drive ahead, the end of the weekend, and the days after that.

My love for you is like a brick. It sits silent in me when you bring out my food at the Dine and Dart, red tray aloft, your skin gleaming like grilled onions. My love is rough around the edges but solid through the center, fresh from the kiln. My love for you is heavy and dark, Jenny, it builds and breaks down, Jenny, it cracks the windows between you and me — you, mixing milkshakes for little league winners, and me, miserly with sandwich wrappers in my car. You, smiling down at the register like a woman with secrets, and me, in agony over the golden arch of your eyebrow.

A brick, inert and dangerous. This love can be worn down but there is always substance to it, always heft, as when you struggle to lift the box of flash-frozen patties, that iced meat against your bare arms, the cold thickness of your flesh a barrier against the protected warmth of your lungs, your heart, your bones. When your manager helps you with that box, the brick grinds in my chest. Your manager, Bill of the blue eyes, Bill of the “no parking” policy, Bill of the fast food tie. He tucks it in his shirt as he walks to the bathroom. You might be kind and claim that Bill is a good man but what you’ll soon learn is that there are no good men, Jenny, none left at all. Not even me, though I’m good deep down, almost to the center.

Читать дальше