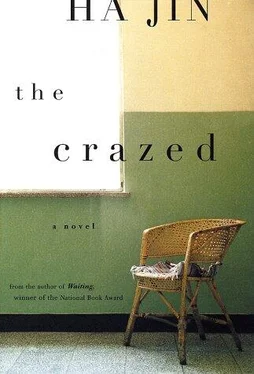

Banping left behind his Jean-Christophe. Gazing at the massive novel on the arm of the wicker chair, I wondered how he could still read for pleasure while looking after our crazed teacher here. Wasn’t he eager to find out the secrets hidden in Mr. Yang’s mind? He didn’t seem interested in his ravings at all. Why was he so detached? He must be either too strong-minded or too thick-skinned. In a way, I wished I were as stolid as he.

Today five minutes after I sat down, Mr. Yang began speaking in his sleep. “As I told you last week, I cannot do anything more for your nephew. I’m not a professor of physics but I already wrote a recommendation for him. Who would believe what I said in the letter? The Canadian professors must take me to be a crook. I cannot put myself to shame again.”

Then his voice wavered as he lisped something I couldn’t quite catch. My interest was piqued. This was the first time I had heard him mention the letter of recommendation. A few days ago Banping had told me that during his shift Secretary Peng often came to see Mr. Yang, talking with him privately. The young man must be her nephew, for whom our teacher had already written a letter. Yet the secretary seemed to have been pressing him for something more. What was it?

Though unable to figure that out, I realized why Ying Peng had been so helpful to Mr. Yang since he suffered the stroke. She wanted him to recover soon so that he could be as useful to her as before.

“Yes, I do know some people in Canada,” Mr. Yang said again, “but they’re all in comparative literature and East Asian studies. I have no connections in the science departments there. How could I help your nephew get a scholarship in physics? Out of the question.” His nose whistled as he spoke.

At last it was clear that the young man wanted to attend a Canadian school as a graduate student, and that Secretary Peng had asked Mr. Yang to secure a scholarship for him. What a silly demand!

“You don’t understand,” Mr. Yang resumed impatiently. “Things are done differently in Canadian colleges, where every applicant has to compete with others on an equal footing.” How ridiculous Ying Peng was. She seemed unable to see that in Canadian and American schools scholarships were not something that could be procured only by pulling strings. Every applicant must reach some minimum standard, such as 1,800 in the GRE or 560 in the TOEFL, and would be evaluated by a committee of professors, none of whom alone could arrange the acceptance of a graduate student. The admission procedures were described clearly in the guidebooks to foreign colleges, and we all had read the descriptions before we applied. A dumb official, Secretary Peng didn’t have any inkling of the admission process.

“That’s entirely different,” Mr. Yang said in answer. “I did write a letter for him, a very strong one. I wrote it not because he’s going to be my son-in-law but because he’s my student, whom I’ve known well and believed to be a promising scholar. You see, even if he’s in my field, I cannot help him get a scholarship. He has to earn it by himself. That’s why he cannot go to the University of Wisconsin.”

Good heavens, he was talking about me! How had I gotten dragged into their dispute? It occurred to me that this wrangle must have taken place quite recently, because the University of Wisconsin had informed me of my acceptance only three months before.

I held my breath, listening attentively as he went on: “Believe me, Jian Wan can be an excellent scholar if he has the opportunity to do graduate work in an American school. That’s the only reason I recommended him. As you know, he’s a decent young fellow, serious and intelligent, though sometimes he’s absentminded.”

Mr. Yang’s good words flattered me. Although he had more confidence in me than I in myself, he would never praise me to my face and instead often called me “my stupid young man.” He once remonstrated with me about my unseemly handwriting, saying with his index finger pointed at my nose, “Your script is like your face to other scholars. I don’t want my students to look ugly. If you write so sloppily again, do not show me your papers.” Since then, I had been careful about my handwriting.

He sighed, then said testily, “You shouldn’t mix my personal life with my professional life. If you think you can lord it over me, you are wrong. Besides, you have no evidence for that.” After a pause, he faltered, “I ne-never thought you could be so unconscionable. You’re very sneaky and even vile. You tried to trap me, didn’t you?” Then his voice turned muffled. I listened hard, but to no avail.

He was so outspoken and even fearless, I was impressed. Did he actually confront Secretary Peng? I wondered. He might have. What did he challenge her to produce evidence for?

His voice grew audible again. “I’m well along in years, and my legs are already stuck in the grave, but Weiya Su is still young. Aren’t you aware that your scurrilous words can destroy her life?” His face, on which drops of sweat stood out, looked dark. His chest was heaving for breath.

Now clearly, Ying Peng had known of the affair and used it to blackmail him into helping her nephew acquire a scholarship. How absurd this whole thing was! Even if Mr. Yang had interceded for the young man, he’d only have made a spectacle of himself. No physics professor would believe his words.

“Do whatever you like,” he declared. “Remember, if anything happens to Weiya, you’ll be responsible.” A spasm of anger distorted his face.

The implication of his last sentence must have been that if Weiya committed suicide, as some young women had done when their romances were exposed, Secretary Peng would be held accountable for her death.

Knowing of his affair, I could feel the tremendous pressure he had suffered when he uttered those defiant words. If the accusation was proved true, it would ruin both his family and his academic life, and Weiya would become notorious as “a little broken shoe” and would be punished as well, at least kicked out of the university if not banished to a small town to teach elementary or middle school. No woman with such a lifestyle problem would be qualified to be a college teacher. Mr. Yang must have been extremely anxious, fearful that the affair would be exposed. So this might have been the true cause of his stroke.

Not entirely. What he said next added something more. “Oh, I have no money!” he wailed. “Where on earth can I get so many dollars!”

Now, it seemed the secretary had resorted to the $1,800 too. How absurd the whole thing had become, totally out of proportion! Just for an imaginary scholarship, Ying Peng would do anything. Why couldn’t she see the logic in his argument? What made her believe so firmly that he could get a scholarship for her nephew from a science department? This was almost like a joke.

“I have no money, no money at all!” Mr. Yang kept yelling and rocking his head. The boards of the bed were squeaking. “Leave me alone. I’ve already written a letter for him. Stop pestering me!”

I felt uneasy that he had stooped to producing the irrelevant recommendation. True, few faculty members here would hesitate to write such a thing, but Mr. Yang had always been regarded as a man of principle and a model scholar. Why had he joined the ranks of liars?

Speaking of recommendations, I had translated into English a good number of them for my fellow graduate students and had seen that the letters were all packed with hyperboles and lies, as if everybody were a genius and, once transplanted to foreign soil, would flourish into an Einstein or a Nabokov. Some of them, applying to American colleges, even fabricated their own recommendations and asked their friends or siblings to sign as their thesis advisers. No American school could tell or would bother to detect the fraud. I knew a young woman lecturer in the city’s Institute of Industrial Arts and Crafts who had gotten admitted to a university in Louisiana on the strength of three letters of recommendation, all composed by her boyfriend and signed by him under different names and titles.

Читать дальше

![Lao Zi - Dao De Jing [Tao Te Ching] (english)](/books/3890/lao-zi-dao-de-jing-tao-te-ching-english-thumb.webp)

![Lao Zi - Dao De Jing [Tao Te Ching] (chinese)](/books/3891/lao-zi-dao-de-jing-tao-te-ching-chinese-thumb.webp)

![Lao Zi - Dao De Jing [Tao Te Ching] (espanol)](/books/3892/lao-zi-dao-de-jing-tao-te-ching-espanol-thumb.webp)