“As you may have noticed,” he said, in his booming chieftain’s voice, “we Bigtrees have a serious enemy. We have a new battle to win.”

“Oh my God,” said Kiwi. “Dad. This isn’t a show. We are all sitting in the same room.”

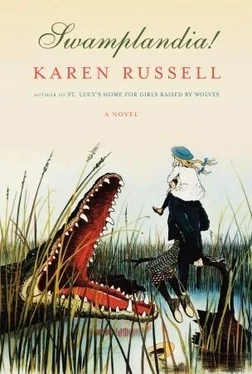

My brother had tugged the brim of his Swamplandia! hat as far down as it would go, practically to the freckles on his nose, which meant that we had to stare at our own cartoon images to talk to him. I think he did this on purpose, to mock us. (I really hated that particular hat — there had been a mistake at the factory and the whole family came out looking hydrocephalic and evil. Tourists would regularly mistake the bump-eyed alligator on the brim for me. They would tap at the grinning alligator on the hat and say, “And who could that one be, young lady?” like they were giving me an excellent present.

“Don’t you take that tone with me, son,” the Chief bellowed again.

“Don’t be an asshole, Kiwi,” I said.

The Chief nodded at me, pleased. “Ava? You want to contribute?”

I shook my head. I had been working on my plan to save Swamplandia! but I didn’t want to talk about it yet; I worried that I would jinx it, or that my brother would kill it dead with one joke. It had to stay in my head for now.

“What’s everybody so damn glum about?” the Chief mumbled. He swallowed his humongous second serving of cake in three bites, and then he quickly finished the half piece that Ossie had left on her plate, his shoulders glugging up and down like an anhinga swallowing a fish. Then he left the dining room and returned with the little blackboard that rested on a tripod outside the Swamp Café. He wiped it clean and stared to write:

Island tameness is the tendency of many populations and species of animals living on isolated islands to lose their wariness of potential predators.

“We Bigtrees are an island species,” he told us. “I’ve been reading your brother’s textbook here.” He hoisted an antiquarian-looking book with the faded coin of a Library Boat sticker on its spine. “Turns out we islanders are very special. A bunch of new and wonderful crap can evolve here because we’re off to ourselves. But there are also trade-offs. Island species get complacent.”

NEW PREDATOR: WORLD OF DARKNESS

he wrote, and beneath this:

OUR EVOLUTION: CARNIVAL DARWINISM

Kiwi chuckled. He could manufacture laughter as joyless as flat cola. “How are we going to adapt, exactly?” he asked the Chief from inside the cave of his hat. “Are we going to hike prices again? ’Cause if we only have two tourists in the stands, Dad, it doesn’t matter how much we charge them. We’ll never break even …”

The Chief continued to write:

REVENUE FOR MARCH: $1,230

OUTSTANDING DEBT: $52,560*

When the Chief put an asterisk next to something, it meant that he was only telling you the best part of the truth. He wasn’t being dishonest, he explained — he was only letting us know that our debt was “evolving.” Just like everything else in this universe. The asterisk, the Chief taught us, was the special punctuation that God gave us for neutralizing lies. One recent example would be “Your mother’s cancer is getting better.*”

“What about the county taxes?” Kiwi asked, very quiet now. “What about Mom’s medical bills?”

“Son, you need to quit on that. You think you’re some kind of detective?”

“What about Mom’s funeral bills?”

“We don’t need to tally those. Those are being taken care of.”

“Dad? I’ve been running some numbers myself … Admittedly, I’m not privy to all your records here …” Kiwi’s voice was as monotonous as a sleepwalk. “For starters, you need to sell some of the equipment. Maintenance costs are going to crush us without tourists. The follow spot, the Seths’ incubators …” Kiwi blinked, as if he’d woken from his sleepwalk on a cliff. “Think big. You could sell the whole park.”

The Chief set his chalk on the little ledge. He stared at our brother.

“Think of what you could get for the airboats,” Kiwi said. “And there are those alligator farms in central Florida, they would buy the Seths I bet. We can finish out school at Rocklands High, I’ll get a job to help out, we can all enroll for the fall …”

Rocklands High. Ossie would be, what, in mainland nomenclature? A high school junior. I would be a freshman, assuming they didn’t put me in some duncey catch-up school. I tried to picture myself in a Rocklands classroom: the place rapidly filled with swamp water, all its desks and books floating away until it became our Gator Pit. We were the Bigtree Wrestling Dynasty. Kiwi wanted to give up our whole future for — what? A sack of cafeteria fries? A school locker?

The Chief echoed my thoughts:

“That’s what you want? To sell your mother’s home? To let some damn Cajun factory farmers butcher our Seths for fifty bucks a head? What’s that? Oh! Less! Have you been doing a little research? To live in the city, ” he snarled. “To go to school …”

While they fought, I frowned and studied the blackboard. The eraser had left a ghostly square on the front of the Chief’s Dijon-golden vest, which was unfortunate because nobody was really doing laundry anymore. Balls of socks and underwear banked like snow around the corners of our bedrooms.

I don’t know what Kiwi was doing for clean clothing during that period; for months my sister and I had been spraying our undershirts and shorts with Mom’s perfume. A strong rose scent. It was in a heart-shaped bottle beveled in tiny gold and pink hexagons with a black rubber pump. It was the fanciest thing in our house by a big margin — tinted and glamorous, foreign enough to feel a little sinister. (We thought of it as an ancient formula; it was a scent called Fox, discontinued in the early 1970s.) Ossie and I had worked out a rationing system: two pumps, per sister, per day. We were using Mom up, I worried, and for some reason that fear made me want to spray on more and more. The perfume worked like a liquid clock for us: half a bottle drained to a quarter, that was winter.

Both my parents had denied that my mother’s illness was serious, not just our father. They claimed that she was getting better right up until the moment that she left for the hospice. Dr. Gautman, her oncologist, was the first to show my brother and sister and me “the chart,” to say “T3c” to us, and to translate this alphanumeric code into the frightening coda of “your mother’s final days.” Dr. Gautman gave us plastic glasses of water with lemon from the nurses’ station before he broke the news to us: “The Malig-Nancy has spread beyond her, ah, her ovaries, I’m afraid …”

And into your mother’s liver, and to the pleural fluid of her lungs . As a kid I heard the word malignancy as “Malig-Nancy,” like an evil woman’s name, no matter how many times Kiwi and the Chief and Dr. Gautman himself corrected me. Our mother had mistaken her first symptoms for a pregnancy, and so I still pictured the Malig-Nancy as a baby, a tiny, eyeless fist of a sister, killing her.

“Nobody is going to a Loomis school . We are not abandoning your mother’s dream here, do you understand that? We are the Bigtree Tribe, son, and we have a business to run …”

Meanwhile the list beneath Carnival Darwinism kept growing:

ADAPTATION 1: INVEST IN SALTWATER CROCS

ADAPTATION 2: WE BECOME AMPHIBIOUS — NEW WET-SUIT COSTUMES FOR THE GIRLS? SCUBA WITH THE SETHS?

ADAPTATION 3: MODERNIZE THE GATOR PIT — ILLUMINATED DIVING BOARD, BUBBLE JETS

The Chief pulled out a booklet of photographs of the saltwater crocs he was interested in acquiring: horned and sad-looking, these crocs did not seem like gods of the Nile. They resembled partially deflated tires. The seller was a retired breeder in Myrtle City, South Carolina, who wanted twenty-five thousand dollars for them. Kiwi flipped the booklet over without looking at it.

Читать дальше