George is ready and waiting.

She plans to count the people and how long and how little time they spend looking or not looking at a random picture in a gallery.

What she doesn’t know yet is that in roughly half an hour or so, while she’s collating final figures (a hundred and fifty seven people will have passed through the room altogether and out of this number twenty five will have looked or glanced for no longer than a second; one woman will have stopped to look at the carving of the frame but not looked at the picture for longer than three seconds; two girls and a boy in their late teens will have stopped and made amused comments about St Vincent’s knot of monk hair, the growth like a third eye at the front of his forehead, and stood there looking at him for thirteen full seconds), this will happen:

[Enter Lisa Goliard]

George will recognize her immediately even from having seen her only once in an airport.

She will walk into this room in this gallery, glance round for a moment, see George, not know George from Adam, then come and stand in front of George between her and the painting of St Vincent Ferrer.

She’ll stand right in front of it for several minutes, far longer than anyone except George herself.

Then she’ll shoulder her designer bag and she’ll leave the room.

George will follow.

Standing close to the woman’s back, so long as there are enough people to camouflage her (and there will be), she will say the name like a question (Lisa?) on the stairs, just to make sure it’s her. She will see if the woman turns when she hears the name (she will), and will pretend when she does by looking away and making herself as much like an ordinary disaffected teenage girl as possible that it wasn’t her who said it.

George will surprise a talent in herself for being surreptitious.

She will track the woman, staying behind her and aping the ordinary disaffected teenage girl all the way across London including down into the Underground and back up into the open air, till that woman gets to a house and goes in and shuts its door.

Then George will stand across the road outside the house for a bit.

She will have no idea what to do next or even where she is in London any more.

She will see a low wall opposite the house. She will go and sit on it.

Okay.

1. Unless the woman is some kind of early renaissance specialist or St Vincent Ferrer expert (unlikely, but possible) there is no way she’d ever know about or think to make the journey specially to see this painting out of all the paintings in the whole of London. This will suggest that for her to have known anything about it, including the basic fact of its existence, she must still have been tailing, one way or another, George’s mother — unless she’s tracking George right now — at the time they went to Ferrara.

2. George’s mother is dead. There was a funeral. Her mother is rubble. So why is this woman still on the trail? Is she tracking George? (Unlikely. Anyway, now George is tracking her.)

3. (and George will feel her own eyes open wider at this one) Perhaps somewhere in all of this if you look there’s a proof of love.

This thought will make George furious.

At the same time it will fill her with pride at her mother, right all along. Most of all she will wonder at her mother’s sheer talent.

The maze of the minotaur is one thing. The ability to maze the minotaur back is another thing altogether.

Touché.

High five.

Both.

Consider for a moment this moral conundrum. Imagine it. You’re an artist.

Sitting on the wall opposite, George will get her phone out. She will take a picture.

Then she will take another picture.

After that she will sit there and keep her eye on that house for a bit.

The next time she comes here she will do the same. In honour of her mother’s eyes she will use her own. She will let whoever’s watching know she’s watching.

But none of the above has happened.

Not yet, anyway.

For now, in the present tense, George sits in the gallery and looks at one of the old paintings on the wall.

It’s definitely something to do. For the foreseeable.

Ho this is a mighty twisting thing fast as a

fish being pulled by its mouth on a hook

if a fish could be fished through a

6 foot thick wall made of bricks or an

arrow if an arrow could fly in a leisurely

curl like the coil of a snail or a

star with a tail if the star was shot

upwards past maggots and worms and

the bones and the rockwork as fast

coming up as the fast coming down

of the horses in the story of

the chariot of the sun when the

bold boy drove them though

his father told him not to and

he did anyway and couldn’t hold them

he was too small too weak they nosedived

crashed to the ground killed the crowds

of folk and a fieldful of sheep beneath

and now me falling upward at the

rate of 40 horses dear God old

Fathermother please spread extempore

wherever I’m meant to be hitting

whatever your target (begging your

pardon) (urgent) a flock of the nice

soft fleecy just to cushion (ow) what the

just caught my (what)

on a (ouch)

dodged a (whew) (biff)

(bash) (ow)

(mercy)

wait though

look is that

sun

blue sky the white drift

the blue through it

rising to darker blue

start with green-blue underpaint

add indigo under lazzurrite mix in

lead white or ashes glaze with lapis

same old sky? earth? again?

home again home again

jiggety down through the up

like a seed off a tree with a wing

cause when the

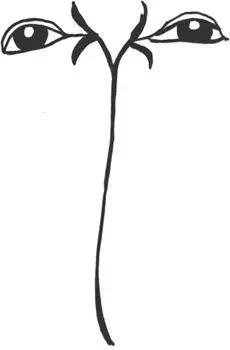

roots on their way to the surface

break the surface they turn into stems

and the stems push up over themselves into stalks

and up at the ends of the stalks

there are flowers that open for

all the world like

eyes:

hello:

what’s this?

A boy in front of a painting.

Good: I like a good back: the best thing about a turned back is the face you can’t see stays a secret: hey: you: can’t hear me? Can’t hear? No? My chin on your shoulder right next to your ear and you still can’t hear, ha well, old argument about eye or ear being mightier all goes to show it’s neither here nor there when you’re neither here nor there so call me Cosmo call me Lorenzo call me Ercole call me unknown painter of the school of whatever you like I forgive you I don’t care — don’t have to care — good — somebody else can care, cause listen, once an old man slept for winters tucked in a bed with my Marsyas (early work, gone for ever, linen, canvas, rot) stiff with colours on top of his bedclothes, he hadn’t many bedclothes but my Marsyas kept him warm, nice heavy extra skin kept him alive I think: I mean he died, yes, but not till later and not of the cold, see?

No one remembering that old man.

Except, I just did, there

though very faint, the colours now

can hardly remember my own name, can hardly rememb anyth

though I do like, I did like

a fine piece of cloth

and the way the fall of a ribboned bit off a shirt or sleeve will twist as it falls

and how the faintest lightest nearly not-there charcoal line can conjure a sprig that splits open a rock

and I like a nice bold curve in a line, his back has a curve at the shoulder: a sadness?

Or just the eternal age-old sorrow of the initiate

(put beautifully though I say so myself)

Читать дальше