I don’t subscribe to that belief, her mother says.

I don’t think you can call language a belief, George says.

I subscribe to the belief, her mother says, that language is a living growing changing organism.

I don’t think that belief will get you into heaven, George says.

Her mother laughs for real again.

No, listen, an organism, her mother says –

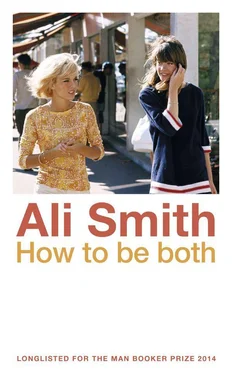

(and through George’s head flashes the cover of the old paperback called How To Achieve Good Orgasm that her mother keeps in one of her bedside cupboards, from way before George was born, from the time in her mother’s life when she was, she says, young and easy under some appleboughs)

— which follows its own rules and alters them as it likes and the meaning of what I said is perfectly clear therefore its grammar is perfectly acceptable, her mother says.

(How To Achieve Good Organism.)

Well. Grammatically inelegant then, George says.

I bet you don’t even remember what it was I said in the first place, her mother says.

Where I’m driving you to , George says.

Her mother takes both hands off the wheel in mock despair.

How did I, the most maxima unpedantic of all the maxima unpedantic women in the world, end up giving birth to such a pedant? And why the hell wasn’t I smart enough to drown it at birth?

Is that the moral conundrum? George says.

Consider it, for a moment, yes, why don’t you, her mother says.

No she doesn’t.

Her mother doesn’t say.

Her mother said.

Because if things really did happen simultaneously it’d be like reading a book but one in which all the lines of the text have been overprinted, like each page is actually two pages but with one superimposed on the other to make it unreadable. Because it’s New Year not May, and it’s England not Italy, and it’s pouring with rain outside and regardless of the hum (the hummin’) of the rain you can still hear people’s stupid New Year fireworks going off and off and off like a small war, because people are standing out in the pouring rain, rain pelting into their champagne glasses, their upturned faces watching their own (sadly) inadequate fireworks light up then go black.

George’s room is in the loft bit of the house and since they had the roof redone last summer it’s had a leak in it at the slant at the far end. A little runnel of water comes in every time it rains, it’s coming in right now, happy New Year George! Happy New Year to you too, rain , and running in a beaded line straight down the place where the plaster meets the plasterboard then dripping down on to the books piled on top of the bookcase. Over the weeks since it’s been happening the posters have started to peel off it because the Blu-tack won’t hold to some of the wall. Under them a light brown set of stains, like the map of a tree-root network, or a set of country lanes, or a thousand-times magnified mould, or the veins that get visible in the whites of your eyes when you’re tired — no, not like any of these things, because thinking these things is just a stupid game. Damp is coming in and staining the wall and that’s all there is to it.

George hasn’t said anything about it to her father. The roofbeams will rot and then the roof will fall in. She wakes up with a bad chest and congestion in her nose whenever it’s rained, but when the roof collapses inwards all the not being able to breathe will have been worth it.

Her father never comes into her room. He has no idea it is happening. With any luck he won’t find out until it’s too late.

It is already too late.

The perfect irony of it is that right now her father has a job with a roofing company. His job involves going into people’s houses with a tiny rotating camera that’s got a light attached to it which he fastens to the end of the rods more usually used to sweep chimneys. He connects the camera to the portable screen and pushes it all the way up inside the chimney. Then anyone who wants to know, and has £120 to spare, can see what the inside of his or her chimney looks like. If the person who wants to know has an extra £150, her father can provide a recorded file of the visuals so he or she can look at the inside of the chimney owned by him or her any time he or she chooses.

They. Everybody else says they. Why shouldn’t George?

Any time they choose.

Anyway George’s room, given time, enough bad weather and the right inattention, will open to the sky, to all this rain, the amount of which people on TV keep calling biblical. The TV news has been about all the flooded places up and down the country every night now since way before Christmas (though there has been no flooding here, her father says, because the medieval drainage system is still as good as it always was in this city). Her room will be stained with the grey grease and dregs of the dirt the rain has absorbed and carries, the dirt the air absorbs every day just from the fact of life on earth. Everything in this room will rot. She will have the pleasure of watching it happen. The floorboards will curl up at their ends, bend, split open at the nailed places and pull loose from their glue.

She will lie in bed with all the covers thrown off and the stars will be directly above her, nothing between her and their long-ago burnt-out eyes.

George (to her father): Do you think, when we die, that we still have memories?

George’s father (to George): No.

George (to Mrs Rock, the school counsellor): (exact same question).

Mrs Rock (to George): Do you think we’ll need memories, after we die?

Oh very clever, very clever, they think they’re so clever always answering questions with questions. Though generally Mrs Rock is really nice. Mrs Rock is a rock, as the teachers at the school keep saying, like they think they’re the first persons ever to have said it, when they suggest to George that she should be seeing Mrs Rock, she’s a rock you know , which they say after they clear their throats and ask how George is doing, then say again after they hear that George is already seeing her and has managed to swap PE double period every week for a series of Rock sessions. Rock sessions! They laugh at George’s joke then they look embarrassed, because they’ve laughed when they were supposed to be being attentive and mournful-looking, and can George really even have made a joke, is that done , since she’s supposed to be feeling so sad and everything?

How are you feeling? Mrs Rock said.

I’m okay, George said. I think it’s because I don’t think I am.

You’re okay because you don’t think you’re okay? Mrs Rock said.

Feeling, George said. I think I’m okay because I don’t think I’m feeling.

You don’t think you’re feeling? Mrs Rock said.

Well, if I am, it’s like it’s at a distance, George said.

If you’re feeling, it’s at a distance? Mrs Rock said.

Like always having the sound of someone drilling a hole in a wall, not your wall, but a wall like very close to you, George said. Like, say you wake up one morning to the noise of someone along the road having work done on his or her house and you don’t just hear the drilling happening, you feel it in your own house, though it’s actually happening several houses away.

Is it? Mrs Rock said.

Which? George said.

Um, Mrs Rock said.

In any case, in both cases, the answer is yes, George said. It’s at a distance and it’s like the drilling thing. Anyway I don’t care any more about syntax. So I’m sorry I troubled you with that last which.

Mrs Rock looked really confused.

She wrote something down on her notepad. George watched her do it. Mrs Rock looked back up at George. George shrugged and closed her eyes.

Because, George thought as she sat there with her eyes closed back before Christmas in Mrs Rock’s self-consciously comfortable chair in the counselling office, how can it be that there’s an advert on TV with dancing bananas unpeeling themselves in it and teabags doing a dance, and her mother will never see that advert? How can the world be this vulgar?

Читать дальше