I went to the old house: he was there, he was fine, he was sitting at the table: there was a written list of names on the wood of the table: the list went all down the long side of it where we’d sat and eaten as children: several of the names at the top end had a line scored through them: they’re the people who owe me for work done , he said, I’m writing to them all to absolve them of their debts, I’ve written to those ones there, I still have these down here to write to .

It wasn’t long after this that they came fast horse to Bologna to tell me he’d died.

In my dreams he was always younger, his arms rope-strong.

Once in a dream he told me he was cold.

But there were nights I couldn’t get near any dream cause the real things I’d seen and done, and seen and not done, fell like a shadow curtain in my way.

I came back to Ferara after he died and stood outside the empty house on the road (cause my uncle was dead and my brothers not wanting to inherit the debts had vanished and left them to me): a woman I didn’t know saw me and came out of a house opposite, she crossed the road and gave me money in my hands that Cristoforo had given her the last time he saw her saying take it, I won’t need it.

4 coins: she wanted me to have them back.

(I lost that contract my father and I signed: I lost that letter my child self wrote to my father: I kept the 4 coins, and had them for the rest of my, till I did I? die?)

I yelled it out into the kitchen.

Nothing I remember nothing.

Through the window I saw the 2 serving girls jump: Barto too nearly leapt out of his own skin. I threw my hands in the air like someone with lost wits: I knocked the cup with the Water of Remembering in it over: it spilled through an open crack in the table wood and hit the floor underneath: the doorways filled with Garganelli servants all wide eyes: Barto held up his hand to stop anyone coming in: he bent low over me, didn’t take his eyes off me: I looked up and through him as if blind.

Who are you? I said.

Francescho —, Barto said.

You are Francescho, I said. Who am I?

No, you are Francescho, Barto said. I’m your friend. Don’t you know me?

Where am I? I said.

My house, Barto said. The kitchen. Francescho. You’ve been here a thousand times.

I let my mouth fall open: I made my face empty: I held my hand up wet from the water on the table: I looked at it like I’d never seen a hand, like I’d no idea what a hand was.

It’s me. Bartolommeo, Barto said. Garganelli.

What place is this? I said. Who is Bartolommeo Garranegli?

Barto went paler than autumnal fog.

Oh dear Christ dear Madonna and all the angels and the baby Jesus, he said.

Who is Christ and dear Madonna and a baby? I said.

What have I done? he said.

What have you done? I said.

I made to stand up, then as if I couldn’t remember what legs were for: I fell off my stool to the ground: I fell quite convincingly: ah but then I felt the wet of the broken eggs in my pocket.

Aw, damnt to hell, I said.

Francescho? Barto said.

Thought I’d got away with it, I said.

Is it you? Barto said.

There was sweat on his forehead: he sat down at the table.

You bastard, he said.

Then he said, Thank the Christ, Francescho.

I got myself to my feet: the wet of the eggs had made a darkness all down my coat and in the clothes on the side of my leg.

For a minute there, he said, my world ended.

I started to laugh and he did too: I put my hand in my pocket and scooped out a single yolk which had — a miracle — stayed whole in its sac in a half-shell of egg still unbroken: the other yolks were mixed up with their own whites and shells and hung off my hand in a long drip of mucus: I wiped my hand on the table and then on the face of my friend, who let me: then I upended the half-shell into my hand and held out the unbroken yolk on my palm to show him.

The oracle speaks, Barto said.

I completely forgot there were eggs in there, I said.

See? Barto said. I told you it’d work.

The girl can’t sleep: or when she does sleep she shifts around in her bed like a fish not in water: in the nights I watch her writhing in the half-sleep or sitting up blank and unmoving in the dark of her room.

The great Alberti says that when we paint the dead, the dead man should be dead in every part of him all the way to the toe and finger nails, which are both living and dead at once: he says that when we paint the alive the alive must be alive to the very smallest part, each hair on the head or the arm of an alive person being itself alive: painting, Alberti says, is a kind of opposite to death: and though he knows that when we are bared back to nothing but our bones ourselves only God can remake us into humans, put faces back on our skulls on the final day and so on &c, which means there is no blasphemy in what I’m about to say –

cause Alberti said it and it is true –

all the same it’s many a person who can go to a painting and see someone in it as if that person is as alive as daylight though in reality that person has not lived or breathed for hundreds of years.

Alberti it is who teaches, too, how to build a body from nothing but bones: so that the process of drawing and painting outwits death and you draw, as he says, any animal by isolating each bone of the animal, and on to this adding muscle, and then clothing it all with its flesh : and this giving of muscle and flesh to bones is what in its essence the act of painting anything is.

I now sense this girl has had a death or a vanishment perhaps of the dark-haired woman in the pictures on the south wall above her bed which are pictures she sometimes looks at for many minutes and sometimes cannot, in which the woman is both young and older, sometimes with a small infant who resembles this girl, and sometimes with another small infant who then matures to become the brother, and sometimes with strangers: in this instance the pictures mean a death: cause pictures can be both life and death at once and cross the border between the two.

Once the girl held one picture of this woman so close to a source of light, to see it more fully, as if to illuminate things in its dark, that I thought surely the picture would burn: but the lights in purgatorium are an enchanted kind of flame and nothing in the end caught fire.

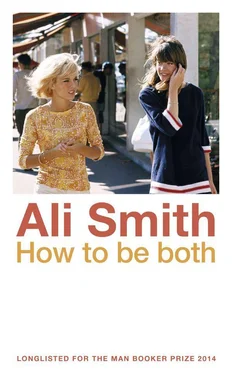

Either this woman, or it is St Monica Victims who is the girl’s loss? Or perhaps one of the 2 girls in the picture on the sunlit street, the 2 friends, the light one and the dark one, one in gold, one in blue: maybe it is all of them who vanished: perhaps there has been a blue sickness here and they have all died of it.

But the girl is an artist! Cause she has peeled down off her north wall all the many pictures of the house we sit and wait outside so often, and she has, on a table in the room, been making a new work out of them and I cannot help but feel I have hit target with her cause the new work is in the shape of — a brick wall.

As if each of the little studies is a brick in this wall, she has lined them up with the right irregularity and she has drawn and shaded with lead the mortar lines round and between each and cut some pictures short for each alternating brickline at the ends of her wall, just like cut or turned bricks look, it does look very like a wall! She’s artisan and can very well make good things: the picture wall is very long and falls and curls off the table on to the floor and part of the way across the room as if the room is a divided territory in which

yes

here come all the memories complete with all their forgettings

doing St Vincenzo for good money in Bologna, I’d got a thick aurum musicum (cause the great Cennini, who is only rarely wrong, is wrong about this gold when he says it is not as good to use as other gold): I had painted my dead father up above Vincenzo’s head in the form of a Christ: not blasphemic I hoped cause my father had so loved and revered Vincenzo, the new saint patron of builders and brickmakers: my father had celebrated his saint day 8 times in the 8 years before he died

Читать дальше