Or our fathers, whose failings while they’re alive (and absences after they’re dead) infuriate.

Or our siblings, who want us dead too cause what they know about us is that somehow we got away with not having to carry the bricks and stones like they did all those years.

Cause nobody’s the slightest idea who we are, or who we were, not even we ourselves

— except, that is, in the glimmer of a moment of fair business between strangers, or the nod of knowing and agreement between friends.

Other than these, we go out anonymous into the insect air and all we are is the dust of colour, brief engineering of wings towards a glint of light on a blade of grass or a leaf in a summer dark.

Let me tell you about the time I was seen, entered and understood by someone I was acquainted with in my life for 10 minutes only.

I’m walking along the road and I pass a fieldful of infidel workers dressed in the white that marks them as worker and makes their skin all the darker: they’re ploughing and planting: I go past freely on my way.

Further on down the road someone springs out from a copse of trees: he’s one of the working men, far enough from the field to seem a touch fugitive. I pass quite close to him: his white clothes are ragged, but less from poverty, I see as I come closer, than from what seems the strength of his own body, as if it can’t help but break through: his sleeves are frayed by the strength of his hands and forearms: his knees have made holes in the cloth, being so strong: the line of dark hairs above his groin sits visible: his eyes are reddened by work.

When I’ve gone a little distance this man calls after me, a word I don’t know.

When I don’t stop, he calls the word again.

It is a benign word as well as a pressing one: something in the sound of it stops me and turns me around on the road.

He is standing in the shade of the copse, perhaps so as not to be seen, maybe more for a rest from the sun, cause I can see even from the distance I’m keeping that nothing about him fears a foreman or overseer: nothing about him fears anything.

Did you mean to call after me? I say.

Yes, he says

(sure enough there’s no one else on the road).

Tell me again, I say, that word. The word you were calling me with.

I was calling you a word in my language, he says.

An infidel word? I say.

He smiles a broad smile. His teeth are very strong.

An infidel word, he says. I don’t know the word for it in your language.

I smile back. I come a little nearer.

What does your word mean? I say.

It means, he says, you who are more than one thing. You who exceed expectations.

He asks me if I can help him. He tells me he needs a twist.

A what? I say.

A —, I don’t know the word, he says. I need to bind my clothes around me, I need a binding thing, for here.

He gestures around his midriff.

You mean a belt? I say. Something to tie?

(cause his shirt is flapping open on him except for one clasp at the collarbone, and it’s March, a cold beginning to the month).

I have a length of rope in my haversack, bought in the market in Florence from a man that told me it was a lucky rope from a hanging and quartering (cause if you carry a hanging rope, it means you’ll never yourself be hanged, he said): it’s a good length and a fair thickness and will probably do: I walk back towards him as he comes towards me: I hold out the rope to him: he looks at it, takes it, weighs it in his hand, then smiles at me as if to pay me with the smile.

When you’ve nothing, at least you’ve all of it.

I have never seen such a beautiful man.

He sees me see this beauty in him and it makes his nature rise.

In the copse of trees at the side of the road there I put my mouth to him and play him like the muse Euterpe plays her wooden flute: then both: he has a smell and a taste about him of grass, clean earth, bread, sweat: he makes redness at the eye a sign of something other than tiredness: he makes calloused hands a means of greater feeling when they go beneath clothes.

We stood up after and I was covered in grass and earth, so was he: he dusted me down: he picked one grass piece off my shoulder and smiled a goodbye, put the piece of grass between his teeth, slung my rope over his shoulder and walked back openly to the fields and the work he’d left.

It was all: it was nothing: it was more than enough.

Fine.

As if the girl knows I’ve come to the end of my story she shuts the love window down dark: the poorly performed love-acts disappear: I think they have not cheered her cause she seems very doleful.

She sits with the shut window on her lap.

We watch a blackbird, with 4 other blackbirds of both male and female type, chase a bird that’s not a blackbird to stop it eating with them at a bush loaded with berries the red of which is the red which the great Cennini in his handbook called dragon’s blood, good for parchment but not for long.

The girl gets up and crosses the patch of grass: halfway across, the brother behind the wicker divide shouts something in their language at her: she calls something back at him, something longer than a name or a stop it , something more like a game or a spell and she walks past the wicker heavy-browed and dismissive: then she’s under a deluge of twigs and little stones and rubble, he is standing on a ledge or barrel and he has them all on a little spade and is throwing them first one lot then the next in the air so they land all over her like it’s raining little stones and sticks: she stops: instead of being angry she laughs out loud.

She stands with her arms out and away from herself and from nowhere her misery is vanished, she is laughing like a child: then she puts the window down on the grass and dives behind the wicker fence, she fells her brother and drags him out on to the grass and the earth, both laughing and rolling on the ground and she tickles him into even more hilarity.

It is a fine thing to see a sudden happiness like that.

She is lucky in such a brother and such a love: between me and my brothers, even though there was nothing between us but air, there were invisible divisions thick as the walls of her room.

Back in that room, the room with the bed in it, back comes the sadness: she sits behind the veil of it for many whole minutes then she shakes herself to her feet and takes off her dusty shirt, shakes the dust and stuff off it out of the window: she shoulders the shirt back on, leaves its buttons unbuttoned and sits on the bed again.

There are many made pictures, all true to life in their workings, on the 4 walls of this room.

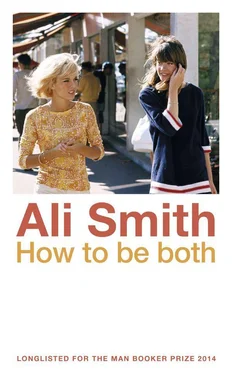

The south wall, along which the narrow bed runs, has a picture of 2 beautiful girls seen walking along like friends do: one has gold hair, one has dark but the dark of her hair is sunlit to lightness — both the heads of the girls are: they are walking along a street with awnings: it’s a warm place: their clothes are mosaic gold and azzurrite: the girls are in conversational commerce and look as if between sentences: the goldener one is preoccupied: the darker-headed girl turns her head towards her in a most natural gesture in open air and so she can see the other better: her looking has about it politeness, humility, respect, a kind of gentle intent.

The picture is by a great artist surely in its patchwork of light, dark, determination, gentleness.

The west wall has a large picture of 1 singularly beautiful woman: her eyes look straight out: there is something just beyond you , it says, I can see it and it’s sad, puzzling, a myster y: this is a very clever thing to do with eyes and demeanour: one of her arms is tight around her neck holding herself, at least I think it is her own arm, and this means the curve of her hair (which is coloured between dark and light) round her face makes her face look like the mask that means sadness in Greek ancients: she is sorry I think: I think on behalf of victims: cause she is a figuring of St Monica I guess from it saying underneath in words that chance to be in my own language M O N I C A V I C T I M S.

Читать дальше