Then there it was. The street entrance of her train. Freeport said, “Here we are. At your stop. And mine — my hotel is right here.”

The grease in Freeport’s hair snatched the lights from the Chesterfield Hotel and glistened like a frog’s back. They were just outside the corona of the hotel, the bow of illumination that demarcated the establishment’s domain from the craggy pavement of the metropolis without. Lila Mae said, “You were going my way all along.”

He winked and cocked his fingers into a gun and shot her. “Would you like to have a drink?” Freeport asked. “The hotel bar is something to see,” he said, “if you’ve never seen it.” The ruby carpet, adept at keeping the city’s gray encroachments at bay, climbed up steps to the Chesterfield Hotel’s brass entryway, up to the light within. She’d read about the Chesterfield. Most people had. The President stayed here on his very last visit. They kept a suite open for him, the newspaper said. She didn’t know they let colored people stay here. Behind Lila Mae, that sullen underground gorge, abandoned to the citizens’ abuse, cracked and stained. Freeport said, “It’s the least I can do to repay you for walking me home.”

“I thought you were walking me,” Lila Mae said.

“Exactly,” Freeport said with a smile, his palm open before the carpet. Of course they let colored people stay here. This is North. She looked up at the doorman, past him and through the glass, made a wager with herself — and stopped. She’d never know the outcome, after all, so there was no point in guessing at the make of the elevators. She said, “I’ll have one drink,” and stepped into the light. Disdaining the hole.

He steered her quickly into the cocktail lounge, allowing her only a glimpse of the famous and fabulous lobby of the Chesterfield Hotel, which she had read about. The Maple Room was subdued that Friday night with the quiet murmuring of couples in sophisticated attire, or so it seemed to Lila Mae, who counted the furs and pearl necklaces snug around delicate female necks as Freeport ordered their drinks. The Department had a dress code. She liked her new suit but it was not appropriate here. Not that she had furs or jewelry locked in a box up at her apartment, but still.

“What do you do with yourself when you’re not out looking for the subway?” Freeport asked earnestly. The piano man kept his head down over his keys.

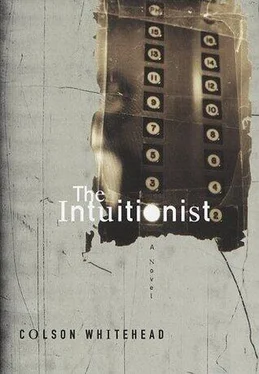

“I’m in the Department,” she answered. “I work for the Department of Elevator Inspectors.” The first time she ever said it. Heavy on her tongue.

“Elevators,” he said, feigning interest in how she spent her daylight hours, but making a good show of it as he attempted to gauge the bulbs beneath those stark lapels of hers, the potential there, continuing to nod his head or stroke his chin as she related that it was her first week on the job and she still didn’t know her way around the office but was getting the hang of it. She had learned, for one thing, that the only ladies’ room was three floors below the Pit, that’s what the inspectors called their rumpus room, the Pit, for reasons that were not yet entirely clear. She was getting her first case on Monday — she’d been riding with a partner all week, an owl-faced grumpus whom she didn’t particularly like, and who didn’t particularly like working with colored people, let alone driving with one. She guessed that some things take a little more time to change, even up here in this city. (Lila Mae did not tell him that Gus Crawford, the senior inspector in question, did not speak to her for their entire tour together. Not a single word, not even to dispatch her from the Department vehicle for a cup of coffee or rebuke her neophyte’s innocent questions, not a word, referring to her only a bit wearily as “the rookie” when asked by the stymied supers and building managers, who, expecting graft as usual, inquired as to who this unexpected third party was. The building representatives left their wallets in their pockets and took their lumps.) But next week she’d get her first case, her first case file. Freeport nodded. He shared his concern that the elevator shaft must be exceedingly dirty and it must be hard to keep one’s clothes clean. She assured him that she didn’t need to enter the well: she could intuit it. She knew he had no idea what she was talking about, but continued anyway, dropping the names of Otis and Fulton, referring to the rival philosophical schools of Empiricism and Intuitionism. He did not trouble her with petty inquiries. He sipped his boilermaker and nodded, urged her to drink up as well, as he’d already gestured for a refill and there she was having barely taken a taste of her Violet Mary. The other colored couple in the hotel bar looked to be African. The woman wore an extravagant liquid red robe, the man a khaki suit with many pockets. They barely talked to each other and drank water.

The new citizens for the new city, the cosmopolitan darlings out on the town, tipped martini glasses and stroked silver cigarette cases engraved with their initials and called the bartender by his name. She had long reckoned on the promise of verticality, its present manifestation and the one heralded by Fulton’s holy verses, but had never given a thought to the citizens. Who the people are who live here. Freeport Jackson calculated the final inch of his cocktail. The dapper men and women traded chatter over gin, white faces pink with alcohol heat in the cheeks, making toasts, discussing escrow. Rich white people, an African couple, Freeport Jackson and his evening’s date. You could never build a building like a martini glass, Lila Mae observed to herself, widening as it got higher like that, it would topple over, foolish. Talk did not travel in that room. Each couple alone with itself. No rowdy groups assembled to celebrate anniversaries or alma mater championship games related over the radio. (She did not tell her companion that she was out tonight so long after the office closed because she had discovered — it was a small office and you could hear the stomach growling of the guy across the room — that the inspectors congregated at a neighborhood bar called O’Connor’s on Friday nights to exchange ribald tales of various elevators and the buildings they lived in, jokes about verticality and its messy effects, to raise a glass to elevators fallen in the line of duty. Didn’t tell her companion that her excitement over this weekly ritual of camaraderie had sent her into the Department elevator at quitting time with the rest of them to depart for said drinking establishment, assuming, in a moment of naive joy over her new circumstances — new apartment, new job, new city — that she was welcome. She walked two yards behind them, their backs to her. Her colleagues did not invite her to sit with them at O’Connor’s defaced tables, did not make any motions for her to join them at the tables, and Lila Mae sat at the bar with the civilian drunks and mumbling-to-themselves Irish nationalists, tasting beer and listening to the elevator brigade’s stories of battles won and lost. No one missed her when she slipped out, abandoning half a beer soon greedily quaffed by one of the keen-eyed drunks, and tried to find the subway home. No one noticed her departure except the bartender, who kept his own counsel.) No rowdies in the Charleston Hotel Bar. Just men and women in negotiations, in smart high-stepping evening wear, careful stitches.

Who the hell is this man anyway. Freeport ordered another drink, Lila Mae demurred; he said, “I sell beauty products. Everybody wants to look good, am I right or am I not right?” He dipped his fingers through the conk waves on his scalp, caressing. “And somebody’s got to give it to them. But you know that already. You’re a salesman yourself. Heck, we both sell the same thing — peace of mind. I’d never try to sell anything to you. You don’t need it, obviously. But most people do. I’ve been in sales seven years now. Seven years — jeez — it still surprises me when I think of it. Up and down the Northeast. I have a good route. I cover the distance. But I’m here now — here in the city — because I just had a meeting with a distributor. The outfit I work for, Miss Blanche Cosmetics, we started small and I’ve been there from the start. We’ve been doing so well we’ve decided to expand and hook up with one of the bigger distributors. We’ve been out there doing the footwork, putting in the long hours, knocking on doors — but a distributor, that’s the big time. I’m the one in charge of getting the deal on paper. Ink. I can’t tell you which company we’re talking to, of course — the walls have ears, you know what I’m saying? — but we’re this close,” demonstrating with his manicured fingers, “this close to having it all in writing. I can feel it. You know how it is, you’re in the elevator and whatnot and you know when it’s right and when it’s not right. Well I think I got it right now. I got it right.”

Читать дальше