On the second floor are the reaping machines and threshers, still and elegant, like lithe animals stooping to lick moisture. The Bowie knives weep in the sunlight; they say Americans are never seen without one. (A quick look around disproves this Continental humbug). A monkey in a sable cape on a leather leash can tell the future. One display features a horse that’s only a foot high and a two-headed infant in a jar, for the children’s delight. The ladies and gentlemen step aside and wave their handkerchiefs in deep respect as he walks by: the Chinese Mandarin and two retainers. (Newspapers later report that he was just an opium smuggler pulling a gag.)

The sound of the organ on the second floor, against which two hundred instruments and six hundred voices would be nothing, so loud on this first day, July 14, 1853, falls away — the heat is even taking its toll on the organ, one man remarks. No, the organ has ceased because the man with the lungs of a bear, the Vice President of the United States, is about to address the assembled: “Our exhibition cannot fail to soften, if not eradicate altogether, the prejudices and animosities which have so long retarded the happiness of nations. We are living in a period of most wonderful transition, which tends rapidly to accomplish that great end to which all history points — the realization of the unity of mankind. The distances which separated the different nations are rapidly vanishing with the achievements of modern invention. We can traverse them with incredible speed. The publicity of the present day causes that no sooner is a discovery or an invention made than it is already improved upon and surpassed by competing efforts. The products of all the quarters of the globe are placed at our disposal today and we have only to choose which is the best and cheapest for our purposes, and the powers of production are entrusted to the stimulus of competition and captial. Ladies and gentlemen, the Exhibition of 1853 is to give us a true test and a living picture of development at which the whole of mankind has arrived and a new starting point from which all the nations will be able to direct their further exertions.” The monkey in the sable cape picks a pocket.

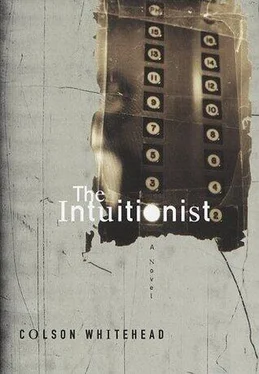

That first night the man attempts to kill himself and does not succeed. It is merely one act of many in the Great Hall, one rough stone among all the gathered jewels of the world. Elisha Graves Otis stands on the elevator platform. No one has seen his act before, and after all they have seen this day, there is little enthusiasm in the Crystal Palace for the unassuming gentleman. Despite his promises of the future. He is a slender middle-aged man in a herringbone frock coat; his right hand strokes a white vest. If the assembled stop to see the act, it is most probably because of exhaustion, the toll of a lifetime’s worth of exotic sights crammed into one glorious day and the swamp heat in the Palace, only now receding with the evening. And there’s nothing new about freight elevators except, perhaps, to some of the country yokels, but not to city folk.

The platform rises thirty feet into the air, grasping for the glass dome above that is black with night. They are drawn from the Persian tapestries and the Egyptian scarabs, summoned from the Ethiopian pots to Mr. Otis, the assembled in the Great Hall come and stare at the platform and the man and the ratcheted rails. They want the future after all. “Please watch carefully,” Mr. Otis says. He holds a saw in the air, a gold crescent in the lamplight, and begins to sever the rope holding him in the air. As the fame of his act grows over the next few weeks and months, the Crystal Palace will never again be as quiet as it is now. The first time is the best time. It is quiet. The rope dances in the air as the final strands give. The platform falls eternally for a foot or two before the old wagon spring underneath the platform releases and catches in the ratchets of the guard rails. The people in the Exhibition still have a roar in them, even after all they have seen this day. A Safety Elevator. Verticality is not far off now, and true cities. The first elevation has begun. Mr. Elisha Otis removes his top hat with a practiced flourish and says, “All safe, gentlemen, all safe.”

* * *

The chauffeur does not speak, he drives, spinning the steering wheel with the palms of his hands. Minute grace of a painter: he makes short, careful strokes, never too extravagant or too miserly. He has a small red cut on his nape where the barber nicked him. As the black Buick squeezes through the bars of the city toward the Institute for Vertical Transport, Lila Mae thinks back to what Mr. Reed said. He said, “Perhaps you are the perfect person to talk to her. She won’t talk to us.”

Lila Mae Watson is colored, Marie Claire Rogers is colored.

The file she holds contains paper of different shapes, grades and thickness. Some of the words are handwritten, some have been imprinted by a typewriter. The one on top is Marie Claire Rogers’s application for employment as a maid with the Smart Cleaning Corporation. She was forty-five years of age when she applied, had two children, had been widowed. The application lists where she had worked previously; apparently she’d spent most of her life picking up after other people and was very experienced in this line of work. Tending to messes. One of her former employers endorses her talents in a letter of reference, describing her as “obedient,” “quiet,” and “docile.” Another document, paperclipped to the application and eaved with the Smart Cleaning corporate logo, relates Mrs. Rogers’s six-months assignment to the McCaffrey household. Her term there passed without incident; Mrs. Rogers’s work was characterized by Mr. and Mrs. James McCaffrey as “efficient and careful.” The McCaffreys moved to cheerier climes, according to the Smart Cleaning Corporation’s records, and Mrs. Rogers was reassigned to one of their regular clients, the Institute for Vertical Transport.

Lila Mae recognizes James Fulton’s signature at the foot of an employee evaluation form, dated a year after her reassignment to the faculty housing of the Institute. Ink identical to that of his signature is observable in small boxes above, where the ink has been used to form x’s in a column of boxes that indicate “excellent.” Except for one box in the “fair” column, regarding a question about punctuality. The date on the form tells Lila Mae that Fulton had just resigned from the Guild Chair (to murmurs of varied volume from the larger elevator inspector industry) to become the Dean of the Institute. The final stage of his career. He’d stolen all the plums; there was nowhere else to go.

The Institute letterhead is more distinguished and staid than the ersatz antiquation of Smart Cleaning company stationery. Rarefied austerity appropriate to a place of higher learning. The document Lila Mae holds is addressed to the Institute’s Board of Directors, and the emotional tenor of the words, the unmodulated panic, provides an intriguing contrast to the serenity of the Institute crest atop the page. The letter urges “swift action” regarding Fulton’s “eccentric” behavior (“eccentric” being a word, Lila Mae notes dryly, that white people use to describe crazy white people of stature), detailed below. Lila Mae has heard most of the stories before — the quick rages, the sudden crying fit in the middle of groundbreaking ceremonies for the new Engineering Wing — but most of the outrageous acts she reads about now are new to her. White people cover their own. Fulton’s behavior does not make her reconsider the father of her faith; Lila Mae does not expect human beings to conduct themselves in any other way but how they truly are. Which is weak.

The next document she finds is no real revelation, either. Fulton has acceded to the Board of Directors, the anonymous secretary reports (with much more enthusiasm than was present in his first document), and decided to resign. He has accepted our offer of allowing him to retain his faculty housing, as well as the proviso that a caretaker move in with him. This particular piece of paper (which shakes with the Buick’s velocity; not everything is within the chauffeur’s control) goes on to describe Fulton’s rejection of all the caretakers the Institute proposed (or “nannies,” as he referred to the pageant of efficient taskmasters who essayed his front door). The woman he wanted was the housekeeper, Marie Claire Rogers. No one else. The secretary is happy to report that Mrs. Rogers agreed, and will move into the old servant’s quarters on the first floor the second week of the next month. Congratulations, gentlemen, Lila Mae says to herself.

Читать дальше