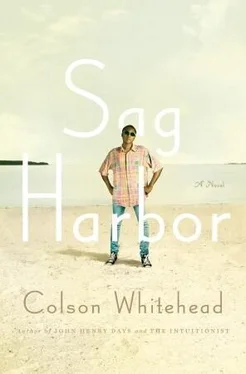

Bobby said he'd pick me up at two o'clock to go driving around. I counted to one hundred, and when I emerged Mrs. Grimes was just disappearing down the stairs to the beach. Good timing. My mother tucked her hair into her bathing cap, an old favorite of hers, white with rainbow-colored plastic flowers floating on it. “Have to get my swim in before those maniacs get out there,” she said. In a few hours, the boats would be zipping back and forth, the drivers with one hand on the wheel and the other in the beer cooler, eyes on the rove for the next escapade. There had never been an accident, but an afternoon in Sag Harbor had special pockets of tsk-tsking that needed to be filled.

My mother looked great. Always this magic happened: as the summer went on, she got younger and younger. The sun tanned her skin to a strong, vital brown, and her thin crow's feet disappeared, ushering an impish twinkle into her eyes. During the week she was a mild-mannered attorney, an in-house lawyer for Nestlé. Every few years, I asked what she did there, and she said, “Oh, you don't want to know about that,” or worse, explained in full detail, causing my synapses to shut down. Something about international trademarks, the protection of the Nestlé family of products and top-secret formulas. We got a big crate of Hot Cocoa with Mini Marshmallows every Christmas that lasted us all year.

City mornings, she armed herself for the midtown hustle, walking out in her monochromatic business-wear and Nikes, her nice shoes in a PBS tote bag. It's a living. But out there, she was a different person. She'd never missed a summer the last forty years. Her friends on the beach were her friends from the old days. Her crew, like me and Reggie had our crew. She wasn't the only one who went back to the start of Azurest, but Sag Harbor worked on her in a way I'd never seen it do other people. There was a part of her that only existed out there. It made her go.

“Sounds like someone is having a party up the beach,” she said.

“That's just Big Dennis and his mix tape,” I said. “Where's Dad?”

“He went down the beach to talk to Mr. Baxter,” she said. She walked down to the water.

I had the place to myself for a while. I ate breakfast and watched Young Frankenstein on Channel 11. Each time I watched it, I got 5 percent more of the jokes. Just killing time until Bobby picked me up. He had a car now, his parents' attempt at seducing him with the sweet nothings of bourgie comfort. I didn't care how the car got there, reveling in the aftermath of our coup. Randy's messed-up jalopy was now in exile, the last-resort overflow vehicle, shotgunned no more. We had reestablished the natural order. Except for the whole girl thing.

The girls just appeared one day, stepping out of their clam. The house came first. We noticed it on one of our early circuits at the start of the summer. It had obliterated a chunk of woods of no special value, bereft of cherished shortcuts and dilapidated hideouts, but it still hurt. It was an '80s prefab joint, no saltbox or rancher, but something you might see if you took a wrong turn and got lost in the suburbs. I'd never been to the suburbs, but I'd seen movies set in sterile subdivisions where over time the dead rotting heart of suburbia was laid bare, and the houses in those movies looked like that house.

The scattered intel and unsubstantiated reports trickled in halfway through the summer. Day One: “There are some girls out,” Marcus declared. “I saw some girls walking up Cadmus,” Reggie reported. “What, little kids?” “No, our age.” “Let's go see.” “No, they're gone, man.” Day Two: NP alleged that “Their names are Devon and Erica.” “Sisters?” “No, man, you see how light Devon is, and then the moms and pops? No way Erica is her sister.” Fact: they were cousins, and it was Devon's house. Day Four's debriefing contained more confirmed sightings, bonehead speculation, and then something new — firsthand encounters. The girls hailed from New Jersey, high-school sophomores to-be. Devon had “those big Lisa Lisa titties,” Erica “a dick-sucking mouth.” “That's too young for me,” Clive demurred, “but y'all should give it a shot.” “I'd hit either one of those honeys,” Randy declared, sharing his enthusiasm for statutory rape. NP presented his conclusion: “Devon would grab your jim with a quickness.” I said, “Really?” By Day Five, it was all over. Bobby and NP called a meeting to announce that they were going out with them, following an eventful afternoon when the cousins “went for a ride” in Bobby's car. I hadn't even met them yet! You go to work, scoop some ice cream, come back home, and the whole balance was off. Cars, man.

“That Baxter is a panic,” my father said, sliding open the screen door. He had an empty glass in his hand, part of a set we bought when we started staying at the beach house, to replace the '60s glasses with mod designs on them, polka dots and odd geometric forms. The old stuff went in the garbage. “What are you doing?”

“Nothing,” I said.

“Time to get a fire started.”

He was known up and down the beach as a master griller, the wind itself in service to his legend, bearing the exquisite smell of caramelizing meat through the developments. Every Saturday, every Sunday, in good weather and bad. On good days, the chicken skin bubbled ferociously, sunlight dancing in the juices, and on bad days the rain evaporated on the lid with bitter hissing sounds. He didn't believe in God but was a devout worshipper of Gore-Tex the Miracle Fiber, grilling into autumn and winter while armored in his beloved Windbreaker. “This stuff really works,” he exclaimed, angry gusts ripping the fabric back and forth. Nor'easters roared up the coast, bringing minor complications vis-à-vis fire-starting, but he always discovered his personal storm-eye beneath the overhang, amid the bluster, the flames ripping with fury in the wind. Autumn days, ours was the only inhabited house on the beach, the bucket of fire a sign of life and ancient caveman lore. He grilled in a blizzard once, as he liked to remind people, for kicks and to prove that he could. You should be so lucky as to witness such a strange and marvelous sight. Shelter Island, the bay, everything that existed outside our property line, was an impenetrable void, a kind of hungry salivating darkness, as the snow swirled like a thousand fireflies into the light thrown out from the living room. We were the only ones left, the last human beings, or maybe the first. The chicken took longer to cook, but when he brought it back inside it was fantastic.

If you told him you weren't hungry, he didn't care. He'd grill anyway. Eventually you'd eat it.

Poomp! Needing a refreshment. How many was that? The one I heard in the bedroom, and probably a refresher at Mr. Baxter's. Plus this one. Starting at who knows what time that morning. I calculated: almost an hour until Bobby was going to pick me up. I could make it.

Before the poomp was the tock of the liquor-cabinet door sucking away from the magnet. You could hear the poomp all over the house; the tock was a slighter sound, inauspicious, given that it was the start of things. It was simultaneously the sound of two things separating as well as the snap of eventualities locking into place. A sequence counting down, tick- tock .

To be completely accurate, you heard the ice first, but sometimes ice is just ice and not an omen. I myself enjoyed a nice Coke with ice from time to time. Ice foreshadowed only intermittently. My father rummaged in the freezer, moving the half-full bag of Tater Tots off the ice tray. Then the ice tumbled into the glass. It was a short fall but it seemed longer. The ice cubes jammed in like inmates. Then— tock!

Читать дальше