There was always a hole somewhere. I dripped a multicolored trail above the previous day's dried trail like a dipshit Jackson Pollock, along the Promenade, around the back of Bayside, to the official Jonni Waffle Dumpster. With some difficulty, I tossed the heavy bags inside, turned — and saw Gabe across the street, leaning against the door of the Tuck Shop, eyeballing me. I looked down, took a step, looked up again, and he was still staring at me. And that expression on his face — was it disapproval?

Not only was my Jonni Waffle T-shirt stinking but now it blazed an obnoxious neon red, the white logo blinking its message: Traitor, Treason, Traitor, Treason. No, we didn't visit Gabe anymore. Once in a while we'd get seized by nostalgia and walk in to play a video game. The place was always empty. The games seemed so silly. How could we have spent so many hours in there, standing like morons, our fingers tapping, eyes glazed? I walked back to the store, looking at the ground. I remembered an incident from a few weeks ago, when Gabe had stopped me on my way to Jonni Waffle saying, “Hey, you guys never come in these days,” jabbing his Pall Mall toward me. And I said, “Yeah,” not even stopping to be polite. I was late for work.

I made it past the Tuck Shop, ignoring Gabe's stare. Who wouldn't be mad at being replaced? Just another smear under Mar-tine's steamroller. Pat pat. “Whatever happened to the Tuck Shop?” you'd hear in the coming years. It was “destroyed by fire.” Next summer it was a health-food store.

The wind was picking up, the sky over the wharf a dirty gray foam. Although I'd only been gone four minutes, the store was packed. Often they came out of nowhere, at the behest of a signal out of range of human ears. Bert caught my eyes as I wriggled through the crowd. “Incoming!” he yelled from the other side.

Incoming, exactly. War and siege analogies came easily in there, during a rush. I was most partial to a scenario I called the Zombie Hideout, given my early training in horror movies: the human beings in the house, the furniture nailed up against the doors and windows to repel the living dead. Dawn of the Dead , with its consumer-society subtext, had its particular lessons. For those who may have missed it, basically the dead have come to life and desire human flesh. In ballerina costumes, policeman uniforms, and terry-cloth robes, the dead roam the streets in search of prey. Once they were normal people. In this entry in the Living Dead series, human survivors have barricaded themselves in a mall, a micro society with all the packaged food and consumer items they could want. At one point in the film, as the characters stand at the doors and look at the hundreds of mindless zombies gathered outside, they wonder what drives them. “It's some kind of instinct,” one of them says. “This was an important place in their lives.” Their brains are gone, but they retain this one thing. I know now that when the living dead come, it will not be at the mall that they gather but at the ice-cream shop.

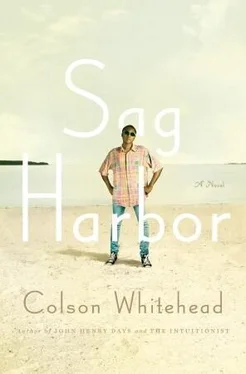

Once in a while, in the city, I'll come across a white person, and Sag Harbor will come up and they'll say, “Oh, I didn't know black people went out there.” Which I always find funny, because until that summer, I thought all the white people I saw in town were townies. Townies with checkered pants. That's how we saw things from our neck of the woods. Working at Jonni Waffle taught me that all those white people who came in couldn't have been townies because if the tiny hamlet had been home to that much miscreancy year-round, it would have been swallowed by the Earth long ago.

They took a number from the pink plastic dispenser and waited, the entire Hamptons. The smell of the waffle cones drew them inside, the same way we had caught minnows with old sheets and bedspreads — they flung themselves toward the open seas of their desire. They wore flip-flops that smacked like wet lips, they shuffled forward in tasseled loafers, in white tennis sneaks, and their polo shirts prowled the entire pastel spectrum, from lime green to Creamsicle orange to baboon-butt pink. They were members of varied fraternities, yacht clubs, golf clubs, secret-handshake groups, they were strivers, inheritors, and the privileged bored.

All kinds of flies out there in the summer, stuck to the gently swirling brown strips.

We served them. Gardeners who spent the afternoons shepherding rows of tomatoes to a vulgar fullness through elegantly gritted overpriced gloves. Retirees shaking their heads over the weekend traffic and hissing invective at the young, young street cops and their new regulations, these peach-fuzz constables who treated them like newcomers even though they'd been coming out for years. The I-Remember-Whensters lumbered in with their musty catalogues of the bygone, dragging IVs of distilled nostalgia behind them on creaky wheels, looking down on the new money and reminiscing about the silent Main Street of yore, when you could walk whole yards without being insulted by sniveling little emissaries of the upstart future. There were people who emerged from big old cars that they don't make anymore, which sat under tarps in immaculate garages waiting for the three days of the year they gulped and started down the lanes, these gawked-at luxury rides of the dead, slowly tooling down the main drags of the towns for all to see and ponder.

They came from all over the East End. The youthful princes who swerved drunkenly down the back roads and were written up by eager deputies who saw their reports crumpled up by wizened sheriffs with a curt “What are you, stupid?” as the police blotters of the weeklies detailed tawdry domestic disturbances next to tear-out coupons advertising “2-for-i Nite at Jonni Waffle.” Indeed police-blotter habitués staggered into the store in between capers. “I think I know that guy.” Those deposited by helicopter, those who putt-putted down 27 in jalopies, those who blessed the Earth with every footstep, those who deigned, those who stooped to, those who would get their pictures next to their obituaries in the Times , and those who would lie on the floor of their abject rooms for days before being discovered.

You got to know the locals. There were people who had uprooted their lives at great cost, the converts who had just become year-rounders with schemes of belonging. Entrepreneurs who fell in love with the silence and the sunsets and convinced themselves that their establishments would succeed against the odds — restaurants serving lovingly produced food of a specialized bent, curio shops whose shelves buckled under knickknacks that were physical manifestation of their owner's psychology. The shopkeepers who shivered with desperation and pounced whenever a visitor roused the sleepy bells over their front doors, the shopkeepers who would take until grim October to accept what was obvious, when they frantically tried to renegotiate their leases, and came into Jonni Waffle less frequently as the summer wore on, as they started to cut back on extras, and when has ice cream been anything but the definition of extra?

We didn't discriminate, we scooped. For the burnouts, the flotsam, the human tumbleweeds who were all of us but for our choices, who found purchase in Springs, outside Amagansett, between towns on dirt roads, in little rooms above Main Street storefronts, in basements of bleak illumination. Magazine editors who assigned articles on the hot spots in order to avail themselves of comps thereafter, oh how they waddled in. The caretakers of other people's property, the people who lived on boats, the painters out to capture that fabled East End light, stoop-shouldered writers ironically digging the affluence while sniffing around for patrons. Posers. Celebrities in shades. Sailors without ships. Descendants of locally famous whalers, whose names hung on street signs to remind people of what they had never known. Potato farmers deliberating offers from developers, the summer influx of help, the waitresses and bartenders and sous-chefs flapping in on their annual migration. Deckhands of yachts on the lookout for wedding rings on fingers, the easy prey, those well-acquainted with knots of all kinds, au pairs stumbling in high heels on their night off and wearing too much makeup and helplessness on their faces. Two scoops, please.

Читать дальше