Paul moves closer to you now and takes you in his arms and starts kissing you again. The sun’s gone lower in the sky, and you think that because it’s darker now, maybe you’re letting Paul kiss you harder, his fingertips more than just brushing your breasts, his body pressing into yours so that you can feel the concentration of the warmth of the blood that’s making him hard. It’s the sound of crying that pulls you apart. Not a child’s cry, but a woman’s. She’s calling for help. When you and Paul get to Dinah, she’s on the ground, grabbing on to her ankle. “I can’t stand up,” she says.

Paul pulls off her shoe to get a closer look. Her ankle, with her skin so white, looks like a large puffball mushroom, the kind that have been cropping up every morning on your front field because the weather’s been damp. “What happened? Did you just trip?” you ask her.

“Yes, stupid me. This never would have happened if I hadn’t been walking with my hands in my pockets. Oh, my phone. Is my phone all right?” Dinah moves her body so she can reach into her pocket, but when she does, her ankle moves, and she sucks in her breath.

“I’ll get it for you,” you say.

“No!” Dinah says. But you have already reached into Dinah’s pocket for her, and slid the phone out. When you turn it on for her, to see if it’s still working, the photo of you and Paul kissing is on the screen.

“The picture doesn’t matter,” Dinah says. “Even if you erase it. I’ll just tell Thomas and Chris I saw the two of you together.”

“What? Let me see that,” Paul says, and grabs Dinah’s phone.

“You’re spying on us?” you say.

“You always think everything’s about you, don’t you Annie? Well, wrap your brain around this. I didn’t come out here to spy on you. I came out here to get some exercise, and then I saw the two of you swapping saliva like some teenagers.”

Paul deletes the photo.

“Come on, Annie, let’s go,” he says, grabbing your hand.

“We can’t just leave her here,” you say. Paul tosses Dinah’s phone next to her hand on the ground.

“She’s got her phone,” Paul says. “She can call whomever she wants to come help her.”

Walking back to the facility, you can’t even answer Paul’s question when he asks you if you’re all right. You’re feeling the familiar feeling all over again. The glistening road, wet from the misty weather, threatening to crack open and suck you down into an abyss you’d never be able to crawl your way out of. But you’re with Paul, and thinking about your brother isn’t supposed to happen when you’re with Paul or thinking about Paul. How is this happening?

Thomas, you think, would not listen to Dinah even if she did approach him with the news. You even think how at first he would probably tell you that Dinah started babbling away at him about you and Paul, and that he didn’t believe her, thought the pressures of being a swim-team mom were becoming too much for her, especially now that her daughter is not winning any more of her races. Thomas would tell you that he felt sorry for Dinah, having to make up such low stories about you and Paul. Thomas, if you don’t say anything to ruin it, might never even believe Dinah, and you could carry on as usual, no matter what absurd stories she may tell him. Because that’s what it is, absurd — a grown married woman kissing her friend’s husband in the woods.

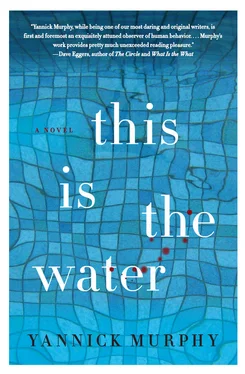

This is the facility, the light coming in from the tall windows above the entrance now a little darker, the sun close to setting. This is you going up to the front desk, telling them there’s a woman on the upper trail at the reservoir who probably sprained her ankle so seriously she will need medical treatment, a clinic, a doctor, some X-rays to make sure nothing’s broken. These are your daughters coming out of the showers after practice. Their hair dripping wet at the ends, creating water stains on their shirts above their small breasts. These are the girls saying almost immediately when they see you, “We’re hungry, what’s for dinner?” This is Sofia saying, “Sounds god-awful,” when you tell her falafel with tahini dressing. This is you not feeling up to driving home just yet and seeing Thomas. “I’ve changed my mind. Let’s order pizza,” you say. These are the girls, cheering in the parking lot as they’re walking to the car. “Saved by pizza!” Alex yells.

This is you pulling into a nearby pizzeria you have seen many times before but have never gone to. These are the girls fighting over pepperoni or sausage. This is you, with a window-seat view of the hillside you and Paul were just standing on. This is you looking at the hillside, scanning it for signs of Dinah, even though you know you wouldn’t be able to see Dinah from so far away and through the gold and red leaves. This is you wishing your girls wouldn’t eat the pizza so quickly. You don’t want to have to go home any time soon and face Thomas. Maybe Dinah has already called him and told him the news about you and Paul. This is the pizza, mostly eaten, mostly, Alex says, because your daughter has just seen the movie Aliens and likes to repeat the line about the aliens that goes, “They mostly come out at night, mostly.” Now your daughter expresses everything this way. She says, “I mostly feel sick, mostly,” and she says, “I mostly feel like not doing my homework, mostly.” And you think to yourself, I mostly feel like not going home, mostly.

This is Chris driving to Bobby Chantal’s daughter’s house. It has glass on the front door that looks as if cold weather has frosted it, as if it were already winter instead of the start of fall. When Pam Chantal opens the door she’s eating a yogurt cup with a plastic spoon. Chris tells her she’s come to the house to tell Pam something amazing, and after Chris tells Pam Chantal that her husband, Paul, was once her mother’s lover, the yogurt cup Pam Chantal is holding falls, spoon and all, to the carpeted floor. Chris tells her what she knows about that night, how the picnic table was their bed for only a short time before Bobby Chantal went to the ladies’ room and was killed. Chris tells Pam how sorry she is. Chris, wanting to protect Cleo from a scandal, asks Pam Chantal to think twice about exhuming her mother’s body, saying that if the body is exhumed, it may actually keep the case from being solved, because so much time would be spent on finding a DNA match for Paul, and he is not the killer.

This is Pam Chantal shaking her head. “I’m not stopping now. You’re the one who gave me the strength to do it. I’ve already made the arrangements. Someone killed my mother, Chris. Someone’s still out there thinking he’s gotten away with it.” When Chris leaves Pam Chantal’s house she’s thinking only of Cleo and how to protect her from being swept up in the biggest crime story in their area’s history, something that could happen simply because her husband slept with a murder victim on a rest-stop picnic table twenty-eight years ago.

T his is the fall night. A coyote’s call quick to pierce the darkness with such a high pitch you startle under the covers. Then a hemlock beam in your timber-frame home cracks. The man who built your house told you the house would do that. He called it “checking,” but you did not know at the time how loud it would sound. It is as if the house were being ripped apart, and you can hear the ringing sound of it in your ears for a moment afterward. But you like the word “checking.” You like to think the house was always making sure of itself, recalibrating, stepping back, getting a perspective so that it could go on, continue being the house it should be. Thomas breathes next to you and you are struck by the thought of all of your family in the house, how each is dreaming a different dream and how even though the house seems still and quiet, each is dreaming of doing things and going places — maybe Alex is flying, maybe Thomas is surfing, maybe Sofia is walking the hallways of her school looking for a classroom she cannot find. You find it surprising that even during the day, when everyone is so close together in the house, in the kitchen for instance, they can’t hear each other’s thoughts. You are floored by how many people there are in the world, and how many different thoughts are taking place at one time. Surely there must be a scientist in some science article Thomas has read who addresses this thought, who has studied it, quantified it, or even just guessed at it, the way they have figured the grains of sand to equal the number of stars in the universe. The moon on the grass makes it look as if your lawn is lit by stage lights, and you would not be surprised if actors came out onto the lawn and held out their arms, gesturing and emoting beneath your window. Who would the actors be? You imagine you and Paul and Thomas and Chris, all standing out there. Thomas set off in the corner of the stage closest to the woods where the coyote calls, alone and quiet, reading his science magazine. Paul at the feet of Chris, pleading with her. And your own likeness, your own Annie actress standing behind Paul, tapping his shoulder the whole time, trying to get his attention, but Paul never turns to her.

Читать дальше