In fifty-three weeks and a day they would marry.

Tuesday, November 14, 2006

Lunch — Last Period

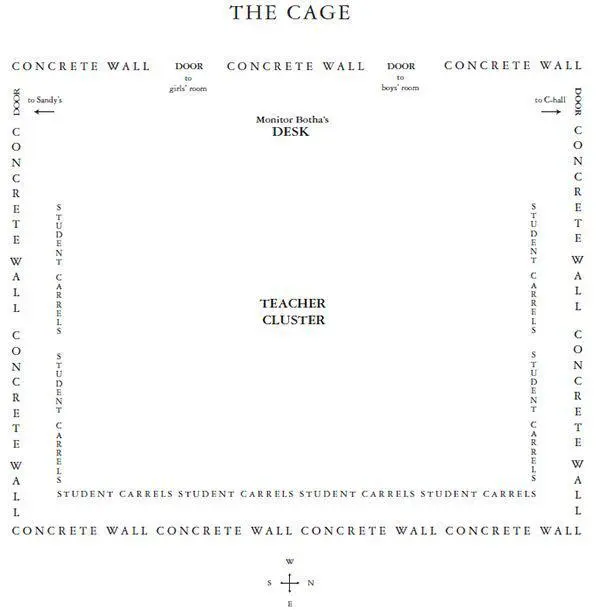

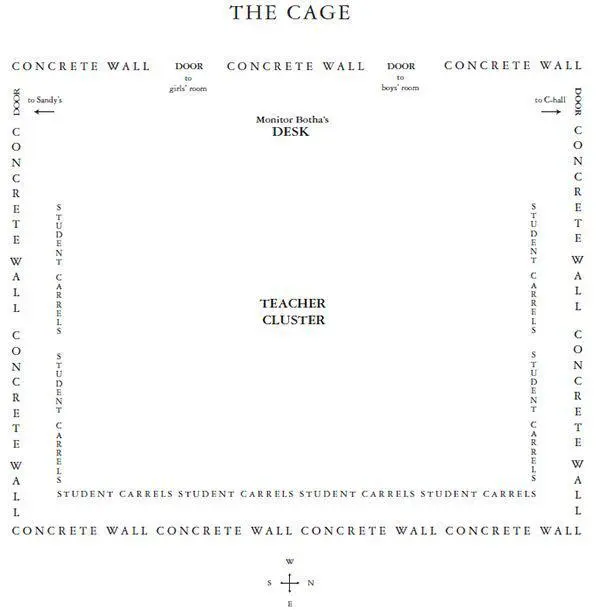

During Lunch-Recess, I sat at the teacher cluster with My Main Man Scott Mookus, Benji Nakamook, Leevon Ray, and Jelly Rothstein. Vincie Portite would have normally been there too, but he had a long-time secret crush on a girl in normal classes — he wouldn’t tell us who — and once or twice a week he’d leave the Cage for Lunch-Recess in order to look at her. No one who was there with me that day had to be except for Jelly. She was on two weeks cafeteria- and recess-suspension for telling the hot-lunch ladies there was a corn on her wiener and it hurt. After she said it, her milk carton dumped out on Angie Destra’s shoes and Angie cried onto the sneezeguard over the pudding. People started calling her “There’sNoUse Angie Destra,” but the name didn’t last because it took too much time to say it, and so it got shortened to “NoUse Angie” and “There’sNo Angie,” which became T.N.A., and that’s the name that stuck because it sounds like T’n’A, and Angie Destra didn’t have any.

Sometimes milk just falls off the tray, and that kind of milk is spilled milk, not poured milk. Spilled milk’s the kind that got on Angie Destra, but people believed Jelly poured milk on Angie, and Jelly wanted for them to persist in that belief since she didn’t like to bite people, and wasn’t getting uglier — not even a little. Jelly Rothstein was a Sephardic beauty in the loudest, sharpest, meanest kind of way. She was dark-eyed and black-haired and wholly unadorned, but light found a way to reflect off her whitely, giving the impression she wore a diamond nosestud and glittery makeup, that silvery bangles clashed and clanged on her wrists, that silvery ear-hoops bounced next to her neck. Her shape was narrow, but she wasn’t skinny so much as she was taut — even in gym clothes, her body called out — and her skin was the brown of lead whitegirls in movies that take place at sleepaway camps in Wisconsin. Like her older sister Ruth, she was one of the sexiest girls at Aptakisic, and everyone knew it, though few would admit it because, unlike Ruth, most girls despised her, the Jennys and Ashleys especially. Why they despised her is hard to explain — it started with her face. It was not a cheery face. Jelly had a way of squinting at the person she was talking to, a way of sucking her teeth, of cocking her chin and twisting her lips, and whereas to me these actions of her face revealed the lithe intelligence at labor behind it, to some — to many — they looked like contempt. This isn’t to say she didn’t harbor contempt for most kids at school — she certainly did — but rather that even toward those she was friends with — me, for example — she made the same faces, and if I had to guess, she’d always made those faces, and by making those faces, she had, unknowingly, alienated herself, which eventually caused her to hold in real contempt the kids from whom she was alienated. After all, she must have thought, what had she ever done to deserve their mistreatment? whenever they spoke, she had paid attention, and she’d even thought hard about what they were saying.

What all of this meant was that guys at Aptakisic who weren’t in the Cage were not supposed to like Jelly, and so those who were drawn to her — most guys were — would be cruel from a distance, shouting out “bitch” or “prude” or “slut,” or, if they found themselves inside her orbit, would shove or molest her with bookrockets, ass-grabs, titfalls, or pinchings. That’s why she’d bite when people got close, especially guys. She’d found that when she hit or choked or kicked, it led to more touching as often as not, but biting through skin, drawing blood with her teeth — that never failed to back off her aggressors. She’d bitten enough people that it was mostly automatic; even her friends had to approach her pretty slowly. Yet she didn’t like to do it — she wasn’t crazy — and, as already stated, she wasn’t getting uglier; that’s why she wanted people to believe that she’d poured that milk. She figured they’d try harder not to get too close to her, and then she wouldn’t need to bite them as often.

But letting people believe that her spilling was a pouring was a bad idea, the oldest kind of bad idea in the world.

On the sixth day of Creation, right after Hashem made Adam from earth, He told him that if he ate from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Bad, he would surely die. But later that day, when Hashem made Eve, He didn’t teach her the law; He told Adam to teach her.

According to mishnah, Adam told her, “If you eat from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Bad, you will surely die. Even touching the tree will kill you.”

That same afternoon, Eve was standing by the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Bad, and the serpent, who was still an unscaly biped, came up to her, saying, “Why don’t you eat a fruit from this healthy-looking tree?” And Eve said, “If I eat from it, I’ll surely die.” The serpent said, “No. You’ll become like God.” And Eve said, “My husband told me what God told him. He told me that even if I touch it, I’ll die.” The serpent knew the Law, and so knew that wasn’t accurate, what Adam had told Eve about touching the tree. So the serpent plucked a fruit from the tree and held it out to her. He said, “I touched it. I’m not dead.” Eve said, “The Law is different for serpents.”

And the serpent shoved Eve and she fell on the tree. “See?” said the serpent. “You’re still alive.”

Then the serpent waved the fruit in the face of Eve.

“You’ll become like God,” the serpent said.

And Eve ate the fruit and she wasn’t dead.

She brought the fruit to Adam and Adam ate it. Not because Eve told him it was a regular fruit, though — she loved him and so wouldn’t lie to him. She told him the fruit was forbidden fruit and Adam ate the fruit anyway because he’d confused himself when he’d twisted the words of God to his wife. He’d confused himself into believing that words from God were the same as words from man. God had told Adam one thing, Adam changed it to another thing, and then Adam forgot what the original thing was; he forgot that the original thing was different from what he’d turned it into. So while Eve was pushing the bitten fruit in Adam’s face, Adam thought: Eve is not dead, I’ll become like God.

But just as God hadn’t told Adam that it was against the Law to touch the tree, He hadn’t said the fruit of the tree was fast-acting poison either. He’d said, “If you eat from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Bad, you will surely die.” “You will surely die.” ≠ “You will instantly die.” Adam, however, had concluded it did, and since Eve hadn’t died instantly after eating the fruit, Adam assumed that God had either lied to him or been incorrect.

The point of the mishna is that it’s even worse to twist the wording of a Law than it is to break that Law, even if you twist it to protect someone you are in love with. If you twist the wording once, it becomes hard to stop twisting it. It’s because Adam twisted it that people die. And that’s why it’s banced to call Eve a temptress. Eve was reasonable, and when it came to Jelly calling spilling pouring, the problem was that she would not always have milk available to pour, and even if she happened to have milk to pour, she probably wouldn’t have it in her to pour it; that’s not the way she was. She’d never once poured milk on anyone; she’d only ever spilled it.

Читать дальше