“If you’re gonna get in trouble, I want to hide. I want more time with you.”

“Maybe I’ll stay quiet.”

“Maybe?” I said. “Maybe’s not good enough.”

“I know,” he said. “Let me think,” he said. He coughed, grabbed his throat. It was totally fake. I remember what it looked like, the color of his tongue, the back of his tongue, blue from the spedspeed — he stuck out his tongue. It was totally fake. If I knew it then, though, I didn’t suspect what he was up to. Sometimes things like that — they look so fake, you assume they must be real.

“Would you get me a water?” he asked me. “I just want to think a second.”

I took his glass off the desk and went to the Quiet Room, turned on the tap, heard Pate shout, “Don’t!” and the door shut behind me. Benji leaned against it. I couldn’t get out. Through the safetyglass I watched him reach for a chair, wedge it under the knob, then go toward Pate, who was lying on the floor, clutching at his knees. Benji said he was sorry — I saw his mouth form the words — and then he turned to me, told me, “I’m coming back,” and I remember the sound, though I couldn’t have heard it, not through the glass, and Benji grabbed a chair and threw it into Main Hall, and then he grabbed another chair and went out the door. One chair he wedged beneath the knob in Main Hall, the other he brought to the gym as a weapon. You already know that. There isn’t much else I can tell you.

Sometimes I don’t like him for having said he’d come back; sometimes it seems to make him a liar. It doesn’t, of course — he had no idea, he was no more clairvoyant than he was suicidal — but that’s how it seems sometimes. Plus he does keep coming back, though, doesn’t he, Gurion? Sometimes I even like that. Mostly I don’t. I can’t fall in love. All the boys who remain in the world are so weak.

I certainly can’t tell you what finally provoked him. Even ignoring that he was high on two drugs, Benji had always been a complicated boy. On reflection it seems that he might have been planning to lock me in the Quiet Room before Pate got there, but maybe he hadn’t been; maybe the news of what was happening outside led him to believe that your plan could work if he could stop Berman from somehow thwarting it. Or maybe the opposite; maybe he thought that your plan wouldn’t work if he attacked Berman, and he wanted it to fail. Or it could be that he wanted you to succeed, but he wanted to keep Berman from being a part of that success. Or maybe it had nothing to do with you at all, and he took what he saw to be his last chance to exact his vengeance on a snake who’d shot him and jumped on his back at the end of the battle.

What’s weird is I don’t even know what you’d prefer to believe. If you were a normal human being, you’d feel vindicated thinking that Benji’s last gesture might have been born of something other than hate for you. But through it all, and after all, you’ve been and remained the same Gurion Maccabee, enmity’s most religious celebrant. The possibility that your best friend’s dying wish might not have been to damage you — might even have been to protect you — probably wrecks you inside just as well as the others.

At least one can hope.

The first time you finish any truly great book that isn’t the Torah, you remember the end the best. *******You remember that event Y followed event X. You recall Y followed X because Y, though unpredictable, was also inevitable, given X’s nature, and given the patterns established by the author (between A and B, J and K, R and S…). ********You may even remember the sweep of the book; how A, itself, led eventually to Y, how each of the interceding events (B through X), if not wholly necessary to give rise to Y, worked to grant Y the resonance sufficient to cause you to supply the book its (unwritten) Z, which must not only follow as inevitably from Y as did B from A, or R from Q, but must, paradoxically, un make sense (if the book is to be other than moralist preaching) of all the above-described causal relations, revealing they weren’t inevitable at all.

All great books command re-reading, but you can’t ever read the same book twice. Knowing, as you do, from the second reading forward, that A will lead to B, to Y to Z, your post-first readings are far more concerned with what exactly happens between those events, far more concerned with those parts you scanned (or even skipped) the first go-round in your rush to discover what would happen next. You look closely at the details — the wordplay, the rhythms, all the “minor” activity — and generate hypotheses as to why they are there, what purpose they serve in the cause of moving you, what they point at, where and to where they misdirect you. This act of analysis creates a sense of distance. ********

When, for example, you already know that Holden Caulfield will run from his teacher who pet him on the forehead as he slept, you read Catcher looking for signs the petting’s coming; you read to determine if Holden’s right or wrong to assume the teacher’s perved. You read this way in order to determine exactly why it was that the scene made you sad: Was it because a man the boy trusted acted like a perv, or was it because the man didn’t ? Soon you realize it could’ve been either — there’s no way to know, each option’s supportable — and you attempt to determine which is sadder: for Holden to have been taken advantage of (or to have been on the verge of being taken advantage of) by a man that he trusted, or for Holden to have been so damaged by earlier experiences that innocent (however seemingly inappropriate) affection from a man he should trust gets misconstrued (misread by Holden as inappropriate) and sends him running out the door. It’s finally impossible to determine which is sadder; not even a hybrid of both is sadder. ********And eventually you come to see that the saddest option is the one that J.D. Salinger exercised: the one that resists disambiguation.

By now, though, the scene doesn’t make you sad; at least not as sad as it did on the first read, when you knew much less about the way it worked. Now, when you read Catcher in the Rye , you observe the scene working to make you sad, and you appreciate those workings (unless you’re a fool), and you examine further subtleties, tinier machines, the sprockets on the cogs behind the wheels behind the wheels. You can’t see the time, though, from inside a clock. You know it, of course — at least you know what it was ; after all, you stopped the clock before climbing inside — but you just can’t see it.

And all of this to say that I remember Benji’s murder and what happened thereafter on 11/17 the same way I remember great books I’ve re-read. I know what I thought and why I thought it, and I know what I said and why I said it, but I don’t remember thinking or saying any of it. I can’t seem to remember the experience of any of it.

What’s left is fractured, gapped, full of empty. Whether that’s because I was, or because — through having gone over it again and again — I have since become so, I cannot say with any measure of authority. Nor can I say which I’d prefer to believe. I don’t even know which I’d prefer you to believe. What’s left, however, is all I’ve got left. It will, eventually, suffice.

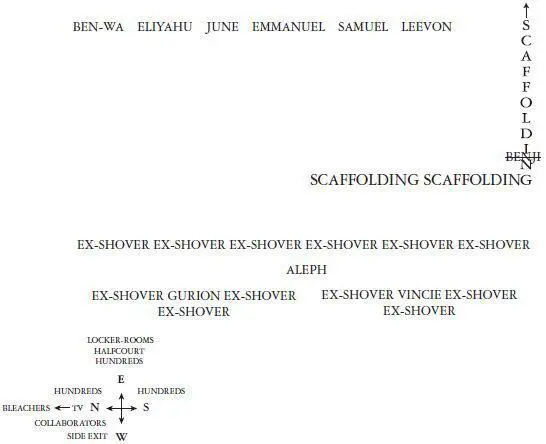

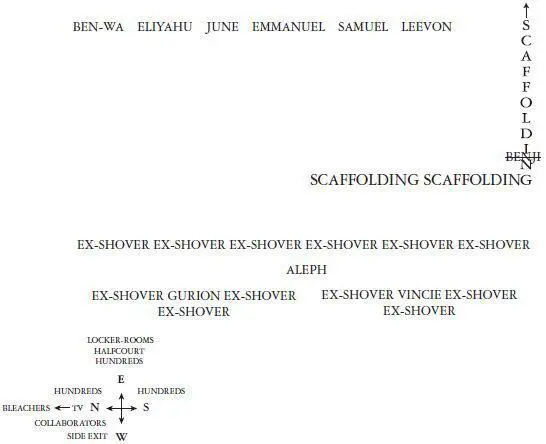

The scholars were coming. Aleph gave orders. Vincie and I were untied from the scaffold and stood at the top of the western key. Two ex-Shover pennyguns, loaded with nibs, were aimed at my throat, two others at Vincie’s, both of us held from behind by the hair. Six ex-Shovers stood shoulder-to-shoulder, facing away from us, weapons trained east. Aleph was standing between us and them. The rest of the insurgents crowded the exit.

Читать дальше