As soon as I revolved, the moment was over.

Friday, November 17, 2006

12:09 p.m.–1:01 p.m.

Abubble of curls behind a thick smear of blood: Googy Segal’s face, mashed flat against glass. Our guards had him pinned chest-first to the jamb. He struggled against them, slicking the blood around, pressing his forehead to the window for leverage. Suddenly he slipped, or someone lost their grip, and his face slid down and the door wedged open. Palms on the pavement, he donkey-kicked blindly; Stevie Loop dropped. Googy lurched a yard, then crawled for another, but out came Ben-Wa, who fell knees-first on his back and stayed him.

Googy made pleading sounds, looked in my eyes.

Let him up! I said.

Ben-Wa climbed off. “He wouldn’t say anything. He just rushed the door. We—”

Googy interrupted. He was up on his elbows, choking on phonemes. Even if I’d been able to make out what he was saying, transcribing it here would be useless. The speech disorders of which Googy was a victim battered his utterances beyond the furthest reaches of any single alphabet’s powers of description — of any three alphabets’ powers of description. There were Chinesey catsounds and Xhosa-like clicks, Tourrettic stammerings and Afrikaaner diphthongs, W’s that might have been L’s or R’s, Hebraic velar fricatives, a storm of whistled sibilants.

I thought I heard “Ally.” I thought I heard “knock.” I thought I heard “knock” somewhat proximal to “mook.”

Benji? I said. Is Benji with your cousin?

Googy just wailed.

Where’s Beauregard Pate?

“He never came back from Nurse Clyde’s,” Ben-Wa said.

Then Googy, though his stammer made it last five syllables, definitely said the word “gym.”

“Benji’s in the gym you’re saying?” Ben-Wa said. “Why’s he—”

Vincie vaulted Googy, into the school. June took his spot, grabbed the Janitor’s collar.

Emmanuel: approaching the edge of the bus circle.

Brooklyn’s in charge, I said. Stay in formation. Follow the plan.

I spun clutching Boystar, hurled him into Main Hall. Jesse Ritter grabbed him. By then I was running.

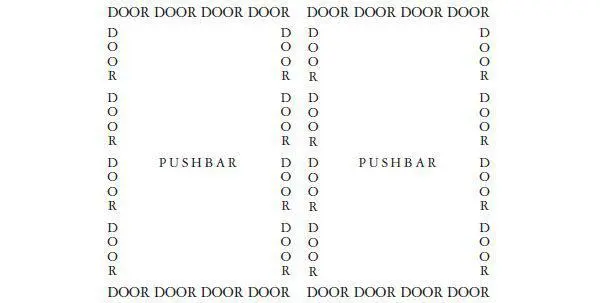

At the gym’s northeast entrance, I pushed on the doors. The doors pushed back.

“They’re here!” someone shouted.

I reared up and charged. The doors blew open. I stumbled on the kid I’d downed, struggled for balance, got slammed against the wall between the locker-room doors. Three ex-Shovers had my wrists and my elbows. I lifted my knee, got one in the nutsack — the one in front of me — he sat down hard. Vincie, at centercourt, was facing away from me, swinging a chair. Kids lay at his feet, clutching their struck parts, crawling away. Beyond them, Benji was draped on the scaffold, and Berman was moving cautiously forward, holding the mikestand lancelike. I couldn’t squirm free of the guys on my arms; I went whole-body limp, and they had to lean in. The one on my left wasn’t all that tall. I smashed his nose flat with the side of my head. On the snapback, my temple met with an edge — the upper southern corner of the fire-alarm — and everything tilted, whited, dissolved.

Some seconds later, I began to come to, aware I was being handled. I couldn’t, for the moment, recall what was happening; I only knew I should resist it. I tried to resist it, but nothing responded. My arms wouldn’t lift. My legs wouldn’t bend. “Tighter,” a kid said. I panicked, inhaled, and my eyes popped open. My chin was on my chest. I was looking at my hands being bound at my waist. Beyond them my legs, being bound at the ankles.

I raised my eyes and I saw Berman swinging. He got Vincie’s chair with the tip of the mikestand. The chair went flying, and Vincie retreated, ran in my direction, a hand in his pocket, looking at something up near the ceiling. He stopped at the free-throw line, hauled back and launched, sending Floyd’s keyring along a broad arc that ended inside of the scoreboard. Berman brought the mikestand down on his shoulder. Vincie half-knelt, popped back up, took another shot to the flank with the mikestand.

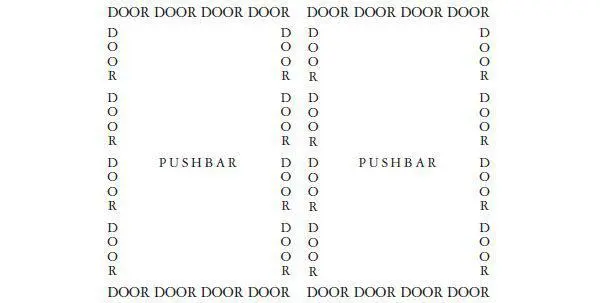

Something to the right of me banged at weird intervals — the northeast doors. I heard the Five cursing, Eliyahu pleading, June shouting my name; for once I was grateful to have been disobeyed. Two ex-Shovers were digging in my pockets, three ex-Shovers dragging Vincie to the scaffold, five ex-Shovers shouldering the doors so one could knot multiple cords between the handles. The doors creaked open for an inch, slammed shut. I tried to roll free; I could roll, but not free.

“Stand him up,” Berman said.

They brought me to my feet, leaned me back on the wall, hands gripping my hoodie. Berman was close now; I couldn’t see past him. His shirt was torn open from neck to navel. His throat looked freshly slapped and kneaded. A bruise had begun to assemble on his ribcage. The kid who I’d nutshot handed him a keyring. Another one handed him a fuller keyring. The first one was Botha’s and the second was Brodsky’s.

Untie me, I said.

“Which one of these keys gets us out of here?” he said.

The scholars are coming.

I could hear Vincie panting, trying not to cry. Banging noise came from the central door now — it was also tied shut. Soon June and Eliyahu would know what to do: they’d get Ben-Wa, who had Jerry’s keys, and they’d come through a locker-room. The locker-room doors were one-way doors; they opened into the locker-rooms and didn’t have handles on their gym-facing sides, so they couldn’t be stopped from inside the gym.

“Which key?” Berman said.

Untie me, I said.

Berman said, “Cory!” and tossed him the keys. Cory’s mouth was bleeding. “Try them all,” Berman told him, and Cory limped over to the pushbar door.

Someone said, “Berman, what should we do?”

“Tie him to the scaffold.”

The him was me. Inasmuch as it was possible, I lunged at Berman’s throat. He stepped to the left and I hit the floor sideways.

They dragged me by the hood toward the back of the gym. Berman followed close, examining my face. Eleven Israelites sitting the bleachers were wet-eyed.

Help me! I said.

They all looked away.

The scholars are coming!

“We know,” Berman said. “Any minute now, they’ll come through the locker-rooms. We’re not worried about that.”

What you’re doing—

“I’m protecting us.”

I can protect us.

“There’s more than one us.”

I’ll protect us all.

“Not anymore you won’t. Not after this. You won’t forgive this.”

I will, I said. Just untie us, Berman.

“It’s not even our fault, you know— he came here. But there was never any way to protect us all anyway — that’s your whole problem. Cause what? We’d get out of here, you’d take all the blame, we’d say ‘Gurion did it,’ and… what? Then what ?”

You’d go free, I said. You will go free. You’re talking in circles. You’re—

“We’d go free, and then what? Where would that have left us? Everything would’ve just gone back to normal. No one would fear us. We’d say, ‘Gurion did it,’ and we’d go free, and you’d be in jail, unable to protect us even if you wanted to. We’d be treated like always, they’d treat us like always, make us crawl on our bellies through filth before them. Better for us we say we overthrew you. Better for us we say we escaped. We didn’t plan it this way, but this way is better.”

It doesn’t have to—

Читать дальше