To all of these questions, the best answer first: Torah is written. The one perfect narrative in the world is written, and not by default — not because Adonai, Creator of the Universe, lacked the technology it takes to make movies, nor because our ancient Israelite ancestors, for whom He bled rivers, split seas, and made manna, lacked the technology to play them — but because truth is best, if not exclusively, conveyed in writing.

The second best answer (for those with a more Nakamookian bent): Video is the chosen medium of tyrants, and that’s not because tyrants lack print technology, but rather because video cannot be examined as rigorously as can the written word. It cannot be as deeply plumbed — at least not yet. The reality a given video does or doesn’t convey, even without effects (allowing, hypothetically, that rendering three dimensions as two isn’t a host of effects in itself), cannot be fully parsed = The viewer can all too easily mistake realism for reality. E.g., every actor in a movie is wearing makeup, but few of them ever seem to be.

Furthermore, while filmed imagery may very well be possessed of a grammar, that grammar is either mostly unknown to us or changing at a pace with which we can’t keep up. It’s impossible to tell. Video may be like a beautiful girl whose every genuine emotion, thought, and intention gets betrayed by the expressiveness of her brow, but that’s of no consequence if we don’t look at her brow. And we don’t, scholars. Not at all. We can’t take our eyes off those fulsome… lips.

I could go on to enumerate video’s other problems — the thousands of ways in which the medium starves the muscles off signifiers, draping the bones that remain in sculpted fat — but that would, at this point, be redundant, I think. In any case, it’d be condescending. You’re well past page 798 by now. Were you not a scholar when you began this book, you’ve certainly become one, and you know it in your heart: books are truer than movies; when they are books of scripture, they are truer, even, than what they describe.

So the perspective you’ll get in this Damage Proper’s telling is that of the first-person-limited omniscient. This is not, of course, because I know everything, but rather because of my particular type of ignorance: because I don’t know how I know what I know, and there is no way to figure it out. First-person omniscience plus this disclaimer — it’s the only honest option. It’s the best I can do.

And lest that last line be read falsely, lest it read humble or apologetic, let me append it:

The best I can do is the best that can be done. I am the author of all of this.

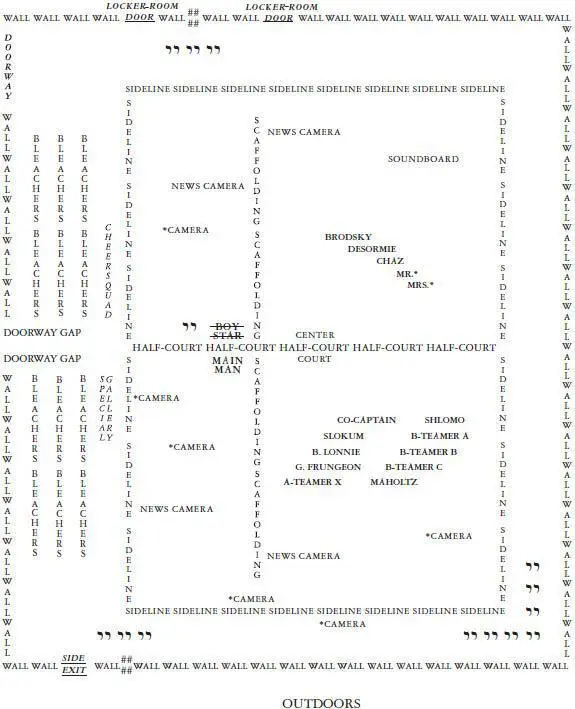

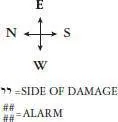

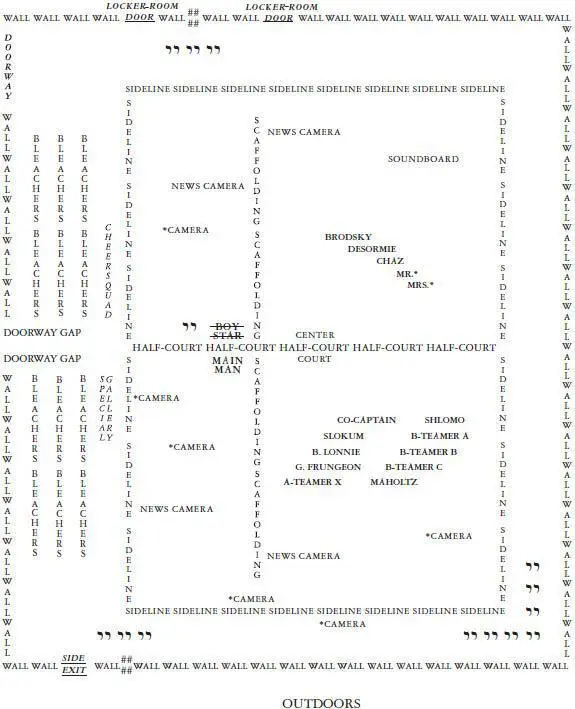

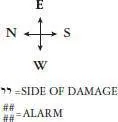

GYMNASIUM at 10:41 AM on 11/17/06

Disoriented basketballers cursing in pain, Nakamook’s soldiers reloading. The Five plugged Shlomo in the eyes with pennies. Eliyahu of Brooklyn vaulted five bleachers. Desormie mumbling hey-nows ten feet east of me, Main Man two-stepping three feet west of me. Brooklyn landing, scanning for Baxter. June was equipping up in her corner, Israelites all across the bleachers were equipping, and all those around them remained ass-to-bench, the Shovers and bandkids and robots alike, and the Jennys and Ashleys, and the everykid no-ones, immobile as anvils, as hunted opposums, pillars of salt, anonymous animals all gawking courtward: here lay Boystar; there stood Gurion; sillhouettes, stage right, were ducking, scrambling; Brodsky as static as his name on a page.

A switch sent current through a circuit when the drums kicked. Panels of lights strobed. Movement looked gapped.

I fell upon Boystar’s chest knees-first, swiping his headset to throw it to Main Man — the rumble of the gooze in Scott’s clearing throat failed to boom like it should have; his feed was still dead — but a keyring was streaking, Boystar’s mother’s, a blur getting thicker in the corner of my eye. I blocked it, just barely, with the hand that held the headset. The ring’s junior maglight cracked the mouthpiece on contact. An asterisk of keys splayed on Boystar’s chin. Its rabbit’s foot, yellow, made his blood look orange. The rape whistle under his nostrils chirped. His mother had the mike by the cord and she swung it. On my knees, I couldn’t dodge but wouldn’t bow, so I turned. My kidney took the blow. I saw white and she tackled me. Ten seconds in, I was already down.

Co-Captain Baxter was still in his chair, a wide-open target, well within range. Brooklyn, just north of the northern sideline, raised his weapon, pulled the balloon back, shut one eye, and aimed. And aimed.

Nakamook knelt in a V-formation. From its apex, rearmost, Benji yelled, “Barnum!” The rest of the platoon yelled, “Barnum! Barnum!” Slokum extracted a nib from his biceps. Another grazed his cheek and he cupped it and ducked.

Shlomo Cohen: hit multiply, reduced to a speedbump.

“Hey,” said Desormie, and then he said, “Hey now!” A nib from above nicked his dextral trapezius. It was meant for the mom, but June’s elbow’d got knocked. Some kids in the bleachers had started to jostle, risen robots and Israelites blocking their vistas. Most Israelites weren’t bothering to sight. They projected from the hip at Shovers in arm’s reach. The Shovers cried out, covered up, got shot more.

The tracers the lightpanels left on your eyeballs were blue and wormy if you looked at the filaments.

Brooklyn kept aiming.

“Barnum!” “Barnum!” “Barnum! Barnum!” “Clear out his lackeys!” Benji ordered his soldiers.

“Excuse me, sir, please, Mr. Mussel, sir, please, but with the height of your stature and the strength of your vision, and this kindness they are speaking every day all the day, all these boys in the band who they play on their horns on my schoolbus to practice to win your fond praise, can you find my good friend who is Beauregard Pate, please, or please to return to a seated position on the bench that you stand so I may see with my own eyes to find my friend Beauregard?”

B-teamers raced for the pushbar-door. Vincie felled the first with a nose-smashing hexnut. The Flunky double-clotheslined the other two.

The gym teacher’s soundgun was ten feet away from me, slung from his neck by a thong like a purse. I wanted to get it for Main Man to sing through, but Boystar’s mom had me pinned and was biting. Twenty seconds in, I was the only soldier down, and Israelites descending— from the bleachers , haters — were finally on their way to help me.

Before you get to the point where you don’t know what hit you, you have to know that you’ve been hit; before knowing you’ve been hit, you have to know who you are. Some in the gym knew better than others. At one extreme was Boystar’s mom, who knew all along she was Boystar’s mom: she got shot in the son and she counterattacked. At the other extreme were those Shovers in the bleachers whose bodies had yet to take any punishment: even those who noticed the cries of their fellows — to be sure, many failed to, their attention on the court — didn’t yet equate those cries with pain, let alone pain brought on by projectiles sent by Israelites out to end Shovers.

Between these extremes was everyone else who wasn’t an Israelite or on the Side. The ones who did know that they’d been hit — Slokum, for instance, who couldn’t fail to realize his pain originated from external forces (the nibs he plucked from his muscles testified); or any given Shover point-blanked in the face — were, as yet, unaware of what hit them; what , in this case, meaning who; who , in this case, being we. And as for how to respond, and whether to respond (which of those decisions gets arrived at first depends less on knowledge than temperament): even for the quickest of those directly stricken, that was still seconds away. For now, they could but duck and cover, or flee their location, or waste some prayers.

Читать дальше