The lights were on, but the gym was empty; third-period PE had swim-unit, too. The end-of-class tone was twenty minutes away, so they’d be at the pool for at least another ten, which gave me time to piss without risk of detection, and that’s what I did, though I only barely had to. I wanted no distractions when I fired on the clock.

In the language of industrial psychology researchers, the locker-room bathroom was a 2S-3U, which meant it housed a pair of stalls and three urinals. According to this study my mother once showed me — she thought it was funny — most guys entering 2S-3U’s go straight for the urinal farthest from the door, unless the urinal farthest from the door is occupied, in which case most go to the one that’s closest to the door so as not to stand next to a guy who is pissing, and if the only unoccupied urinal’s the middle one, not only do most guys go to one of the stalls, but even though all they’re doing is pissing, they stay for much longer than it takes to piss, engaging in what the authors of the study term “the phantom defecation stratagem” because they are embarrassed that they didn’t choose to go to the unoccupied urinal and they feel that they need to save face.

I’d never once phantomly defecated, myself, but my choices in bathrooms, apart from that, did used to be typical. After I’d read the study, however, I quit going to the urinal farthest from the door. Whenever I’d enter an empty 2S-3U, I’d head straightaway for the one in the middle. What that did was cause most guys who came in after me to go to a stall. More than most guys, really; nearly all guys. Say eight out of ten, and call the stat reliable— I pissed a lot. Every day of the week, I beat the good sage’s minimum, and usually I beat it by the end of dinner.

The Rambam (aka Maimonedes of Cordoba) said you had to piss at least ten times a day if you wanted to be a good sage. He also said you should keep your stomach in a constant state of near-diarrhea, which is not to be confused with a near-constant state of total diarrhea, which is the way of the stomachs of scoundrels worldwide. It is also important, according to the Rambam, to keep yourself clean. That is why I’d wash my hands every time. Even though doing so made people think you got some piss on your fingers. Rambam was a wiseman.

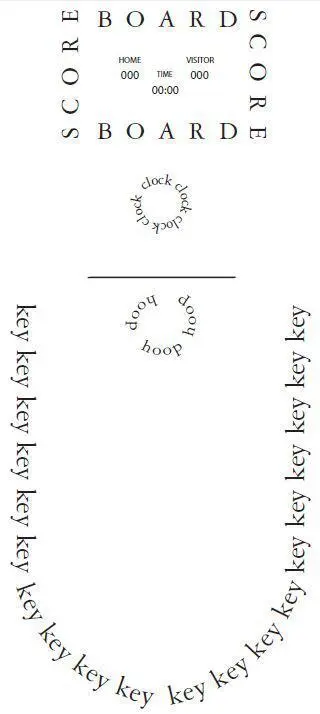

I finished up pissing and scrubbed with pink soap, dried my hands on my pants, and returned to the bright and empty gym, where my every step echoed and my breathing seemed loud. The clock was high on the western wall, ten feet over the basketball hoop, just a few inches below the scoreboard. It was masked by a box of metal rods with spaces between them too narrow for a golf ball, or even a marble, to get through. A coin, though, was thin. A coin could sneak.

Once, I got a couple pennies through the mask. All that they did was bounce off the glass, but pennies are smooth-edged, and that was the reason, apart from sheer mass, that I’d thought to try quarters. Quarters are rough-edged, and also they weigh more, and I thought that the glass might be like a man, and the edge of a penny like a bed of nails, whereas the one or two points on the edge of a quarter that would impact the glass were more like one nail that, if it was laid on, would enter the flesh.

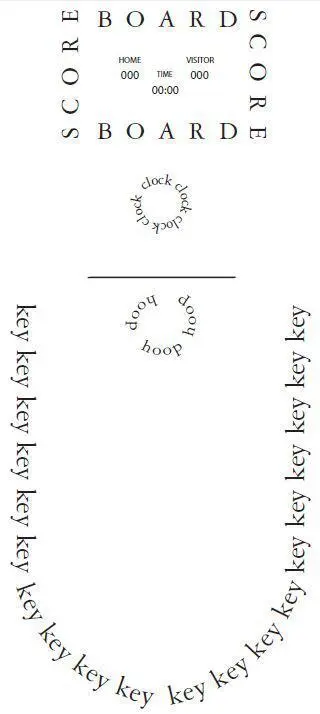

I dropped a quarter into the balloon and stood at the top of the key. When I kneeled down to aim, it said 10:25 on the clock. I didn’t know if it could happen, but I wanted the clock to stop when I smashed it, and if it stopped, I thought it would be better — a better gift to June, in case she noticed such things — if it stopped at a time that was interesting. 10:25 was not so interesting. Though 2 x 5 = 10, it’s a cinch. And 10:26 did nothing when you played with it. So I decided to wait for 10:27, since 1+0+2+7 = 10.

While I waited for 10:27, I could only hear my breathing and I remembered June kissing me. Not just that she kissed me, but the way the kiss felt, on my skin, in my skull. I got a shiver. When it faded, I tried to get another but couldn’t. I’d worn out the memory, at least for the moment. If I thought too much about anything good, it would get less good, and everything good would begin to seem temporary. I did that the most with good songs. They’d stick in my head and go dull. And even when I’d hear one in my ears again, there were no surprises. I’d anticipate all the notes and the beats and the song would be ruined. So while it wasn’t any big deal that I wore out the memory of that one kiss, I was scared that if I kept remembering the kiss I could ruin future kisses, so instead I remembered June saying, “Don’t be sick, Gurion. I like you,” and I got another shiver and it was 10:27 and as soon as the shiver stopped I pinched the quarter through the balloon skin and pulled back on it. I was aiming for the most middle space of the mask, the one that had the 3 and the 9 between it.

I let fly and the quarter plinked the bottom of the rod beneath the twelve, then fell straight down onto the floor. It was bad that I missed, but good to discover that my pennygun could project quarters.

It was still 10:27. I dropped another quarter in the firing pouch. This time I aimed for the space with the 5 and the 7 between it because it seemed from the first shot that I had aimed too high. There were fourteen seconds left in the twenty-eighth minute of ten o’clock. When there were thirteen seconds left, I fired. I got a direct hit, right in the middle between the 3 and the 9. It made the noise tock , but nothing else happened. The glass didn’t fall down in pieces like I wanted. The clock didn’t stop. There weren’t even cracklines. Improbably, the quarter came to rest inside the mask; it lay flat on the centermost rod along the bottom.

I’d been wrong about quarters; they wouldn’t do the trick. I’d smashed windows with pennies, so I was surprised. It was 10:28 and 1+0+2+8= 11, so it wasn’t as good as 10:27, but it was better than nothing, and I just couldn’t wait for 10:36. Though the period wouldn’t end for sixteen more minutes, Desormie had to let class out extra early because the showers would bottleneck since even the dirty kids — even some of the shy ones — preferred to get warm and lather the stiff chlorine stink off their skin. If he stayed in his office while everyone showered, Desormie wouldn’t hear me, but he was just as likely to stand in the gym and admire the scoreboard. He did that sometimes.

I’d have to work quick.

Since the pennygun could fire quarters, I figured it could fire small wingnuts, too. The problem was I’d given all the wingnuts I’d brought that day to June and the principal. I ran to the bleachers to see if I could find one — no. The bleachers’ joints were fixed with welded-on hexnuts.

10:29, nearly 10:30.

I thought about shooting the rivet on my jeans-pocket that I used to call the grommet until my dad said it was a rivet, and then I thought about the bottom eyelet on my Chucks that was a grommet, but a specific shoe-kind that was better called an eyelet, but neither of those things was any heavier or pointier than a quarter, plus in order to get one I’d have to tear my jeans or cut my shoes and thus anger my mom, so both ideas were completely dental.

I opened the back door of the gym where there was an asphalt trail. Next to the trail was some mud with rocks in it. I kept my foot wedged between the door and jamb and searched for a rock that would fit in the gun. The effort got me H, but I found three in all, each irregularly shaped: one like a dog’s ear bending in kindness, another like Nevada, a third like some lips with a sore in the corner. I fired Nevada first, because it was the slimmest, and also the pointiest. Nevada got wedged between the bars of the mask. It was 10:31, almost 10:32. I felt all defeated. I felt like exploding. If the slimmest and pointiest of the three couldn’t penetrate… I let fly the dog’s ear without really aiming; I let fly from pique; I fired from the hip. The shot was way high. Not even close. It blew out the E of the HOME on the scoreboard. The E hit the floor in three sharp pieces. The bulb remained. HOME was now HOM.

Читать дальше