I was still too happy to just go to the Cage. I wanted to do something — I wasn’t sure what. I flipbooked the passpad, made it a cylinder, flattened the cylinder, pocketed the passpad. I tried to break my fingers and my fingers wouldn’t break. I poured the bag of wingnuts in my hand and they jingled. The paint on the wings of the black one was nicked; this was the one with which Nakamook had blown off the rockinghorse’s face while June and I kissed on the stage in the lunchroom. CHUCKETA-CRACKETA. That was the noise it made. I pinched it between my thumb and pointer. It was small enough to sneak, if I wasn’t mistaken, between the metal rods of the gym clock’s mask.

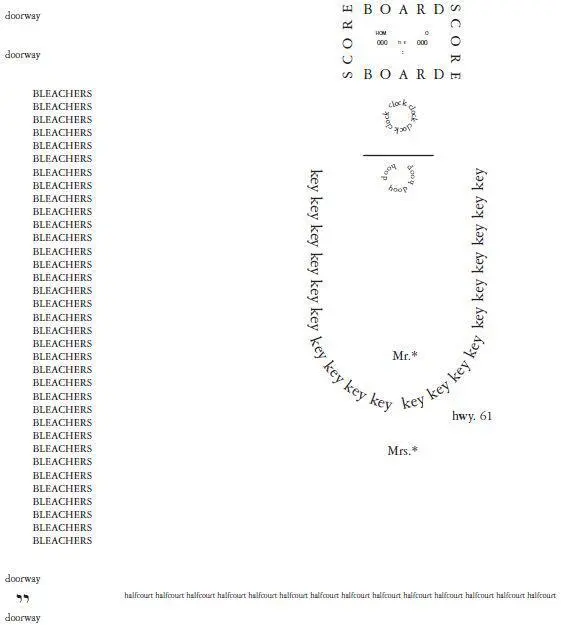

The gym wasn’t empty like it should have been. Boystar was throwing a tantrum under the hoop beneath the clock. The heap of scoreboard wreckage had been removed, and he stomped on the spot it used to occupy, yelling “Jesus! Jesus Christ!” At “Jesus!” he raised his arms. At “Jesus Christ!” he slapped his hips. The person he was yelling at was his father, who stood slump-shouldered at the free-throw line, his pomade bending light into a halo. He shook his head = “No, this behavior is nothing I can brag about,” and the halo got dull and tilted.

I was in the midcourt doorway, trying to be a wall. It wasn’t easy. B-Hall doorways were smaller than C-Hall ones. They barely buffered sound and their shadows were thin.

“Listen to me!” Boystar was yelling. “Please! I’m telling you!” He kept raising his arms up and slapping his hips.

There were other people there, too, but none of them watched the tantrum.

At the top of the key, Boystar’s mother was crouching beside the Highway 61 acoustics man I’d seen the day before. He knocked his fist twice on the floor in front of him, then revolved and did it again. The mother leaned in.

Another man was on his knees on the bleacher-side sideline at half-court. He was outlining three sides of an air-rectangle like actors playing directors do in art movies about old Hollywood. He squinted through the rectangle and tsked his tongue in concentration.

My chemicals were ticking. How could I smash the clock with all these people in my way? Why was this guy framing shots on the sidelines? I dropped the black wingnut into my pennygun.

If I shot the clock and the shattered glass fell like I imagined, shards would slice off Boystar’s nosetip and knife deep into his shoulders, his feet. The problem was the bleachers — they blocked my vector of attack and there was nothing I could do about it. Even if I risked moving to the center of the doorway and edging into the gym proper, where anyone in there could see me if they turned their head, the post the hoop hung from would deflect the projection.

Could I run at the acoustics man, shove him out of the way, then shoot the clock from the top of the key?

A guy in a suit as metal-looking as the hair of Boystar’s dad came out of the door of the boys’ locker-room. “Our star the Boystar!” the guy said to Boystar, adjusting his belt.

“I’m not happy about this, Chaz. I’m not happy about this at all,” said Boystar. “I’m really fucking unhappy.”

The guy in the glitzy suit — Chaz — put his arm around Boystar’s shoulder and whispered something in his ear.

Boystar said, “You’re a real sweetheart, too, Chaz Black, but that’s got nothing to do with anything. Emotionalize is about being sexy.”

Explosive as I was getting, I probably could move the acoustics man and hit the clock. Or I could even just race across the gym and hit the clock running — my chemicals were making me simple; my aim would be true — but I would get seen, caught.

Chaz said, “Sexy is as sexy does, my friend.”

Boystar’s dad clutched his own neck and looked at his feet.

As if he knew what I’d been considering, the acoustics man moved to the southeast corner of the gym. He struck a tuning fork and said, “Nice.”

It was too soon to get caught. Would it always be too soon? I didn’t think so, but I knew it was too soon right then. I turned my pennygun upside-down above my palm and shook it til the wingnut fell out.

Boystar’s mom touched the elbow of the acoustics man. “Is that a tuning fork you’re using?” she asked him.

“Sexy people aren’t diseased,” Boystar said. “And you said I’d get a blue faux-hawk and we’d shoot in LA and you’d CGI me doing fly aerial shit in halfpipes. You tricked me and it’s stupid and I’m thinking hard about hiring a lawyer.”

There was an X of masking-tape on the sideline where the shot-framer had stood. He was working his rectangle at halfcourt now.

Chaz was saying to Boystar, “No one tricked you, buddy. Circumstances have changed. And for the better, I might add. Frankly, we got lucky. This video’s gonna nice up your image and it ain’t gonna cost much.”

“I don’t care what it’s gonna cost. I’m gonna be rich. I’m gonna be so rich. The only reason I even agreed to sing with that retard was so Brodsky would let me go on tour. Like that ever even mattered. Tch. If he had any faith in me,” said Boystar, pointing at his father, “he’d know how big I’m gonna be, and he’d just withdraw me from this shithole and hire a tutor. Now the whole world’s gonna see me chumming some Jerry’s kid? Emotionalize is not about dances with retards, Chaz. It’s about being sexy.”

I pulled pennies from my pocket.

Chaz said, “Listen. You treat this Mookus with affection — smile at him, put your arm around his shoulders, make wowie-zowie kindsa faces if he breaks out the fancy footwork like they do in that sensitivity-training video we watched together — and all this advance negbuzz we’re getting about Emotionalize being too explicit for the tween set is gonna disappear forever. Churchmoms around the world are gonna be humming ‘Infantalize Me’ over the pot-roast like it was the Cats! soundtrack or something. And ‘The Way You Mmm’? Forget about it. Platinum.”

“I’m a star,” Boystar said. “I’m a star and I’m sexy and retards do not move units.”

I dropped a penny in the balloon and I aimed.

“I want to get a punky haircut and dress like a skateboarder. I want—”

I shot him in the knee and he dropped to all fours, yelling, “Help me! Something happened! Help me!”

“Stand up and stop acting like an idiot,” his mother said.

“Something happened!” Boystar wailed.

“Get off the filthy floor,” said Boystar’s dad. “You are ruining your slacks.”

“My slacks ?!” yelled Boystar. “I’ll ruin my slacks ?! How about this, Dad? Emancifuckingpation! I want emancipation! I’m gonna fucking sue you for emancifuckingpation! You can fuck these fucking slacks in the face with a big fucking stupid fucking… cock! For all I care. But I’m gonna be rich , and you won’t get my money! You won’t get fucking shit! Ruin your fucking slacks! How do you like that , you fucking fucker stupid ass?”

I didn’t get to hear what his father’s response was. I’d been heading west slowly since the first “emancipation,” doing the walk of the oblivious innocent, and after “fucker stupid ass” I was too far away.

I cradled a ball of gooze in the curl of my tongue and rang the Cage doorbell. As soon as Botha came to the gate, I fake-sneezed the ball into the middle of my hall-pass, and tried to hand it over.

Читать дальше