I went back. It had to be after six, but not yet seven. A group of men sat at the pub, a bucket, a trowel, and a level at their feet. They looked like proletarian freemasons. Drinking vodka straight, with beer as a chaser. No trace remained of the evening carnival; the ashtrays on the table were clean. The men hardly conversed. Heat came from the east, and the shadows of people diminished like wet blotches drying. The masons drank up and left. The babushka promoter appeared, brush in hand, a rag wrapped around it, and wiped everything along his way: the curb by the pub, the concrete divider, the sidewalk. He did this quickly and efficiently. The rag, dry, left no mark. He disappeared around a corner, appeared again at the far end of the sandy square before a store, and did his hurried cleaning there too. For almost an hour I saw him come and go, in a constant rush, trousers bagging as he did battle with dirt and dust, a Buster Keaton of the Delta trying to stem the chaos of volatile substances and defend Sfântu Gheorghe against the rain of particles from outer space.

The masons returned, but now without their tools. Once again, glasses of vodka with beer chasers. Evidently they had started a job and so now with a clear conscience could, without haste, take the measure of the new day. More people gathered at the tables. It was after seven; the sky took on a dull milky hue and began to swell. I drank Ciuc and Ursus, alternating, wanting to be less conspicuous in this morning company, to participate in the fatigue that came from their faces and bodies. Sleep in this place, apparently, took as much effort as getting through the day. I would have loved to sit at the wooden table until my soul sank out of notice, until my limbs became immersed in this strange soup of dawn and dusk. It is possible that my perverse love for the periphery, for the provincial, for everything that passes, fades, and falls apart had found peace at last in Sfântu Gheorghe. I could sit here for years and grow comfortable with death. I could go out to the ferry dock every day and watch death come in. The worn, threadbare measurements of time would hasten its arrival, or delay it, and eventually I might acquire a kind of immortality. Because if life was extinguished here so easily, death would have to take on some thinned-out, spectral aspect. In my daily walk between the shadows of the pub's lindens and the harbor, I would keep just enough of my energy so my mind wouldn't shut down, so I could continue imagining the world, make sure I had lost nothing. At noon, when boredom struck, I would walk to that flat sandy stretch along the shore. From inland would come mirages of distant cities. Between the mirror of the water and the clouds, Bucharest might appear, Berlin might float, Prague, London, Istanbul, and, with the right combination of light and convection currents, a fusion of New York and Montevideo, Tokyo and Montreal. Atmospheric-optical flux might also let me view my past life, my gestures and actions preserved among the layers of air, frozen in stratosphere lockers but now reanimated for my amusement or moral instruction. In Sfântu Gheorghe anything could happen — I was convinced of this around seven thirty, when the first guests sat down at the tables. There are places where only potentials exist. And in this place the only way out might indeed be a miracle, a sign, a sudden revelation. Void, paralysis, the horror of decline, the sorrow of elements forced to assume geometrical shape, earth and sky pulling at weary, sleepy humanity in either direction — all this in itself was miracle and sign, stopping the imagination in midstride, replacing it with implacable reality.

I finished my Ciuc or Ursus and got up. The schemes I had dreamed of were so alluring that I needed to take some action. At the dock, a couple of boats were anchored. On a board hammered to a mast, someone had chalked "crap 35000, som 38000." The prices for carp and catfish. Two men sat by a wooden shed. I went up to them and asked how people got out of here. Was there a boat to Sulina? They mulled awhile. Finally one said no, there was no such boat, not in the whole village, no one was going out, and there was no ferry until tomorrow. I heard the same thing from men who were tarring a dinghy that had been hauled from the water. Anyone I asked, it was the same: No one is going out. I didn't really want to leave, I just wanted to know. Everyone spoke of the ferry and sometimes of a tractor that at five in the morning set out through the marsh toward Sulina. The thought of tomorrow's ferry depressed me; I intended to take it but not that soon.

At a shop I bought bread, caşcaval cheese, mineral water, and white wine in a plastic flask. I made for the beach. At eight, it was as hot as it is at noon at home. The ground smelled of cow dung and dust. I found an isolated spot. When I waded into the sea, the water was as warm as the air. The bottom barely dropped. I went out so far, the land became a thin line, but even so the water hardly reached my chest. Now and then I felt a cooler current, but it was gone in a moment, and once again it turned as warm as if I were sinking in enormous, churning innards.

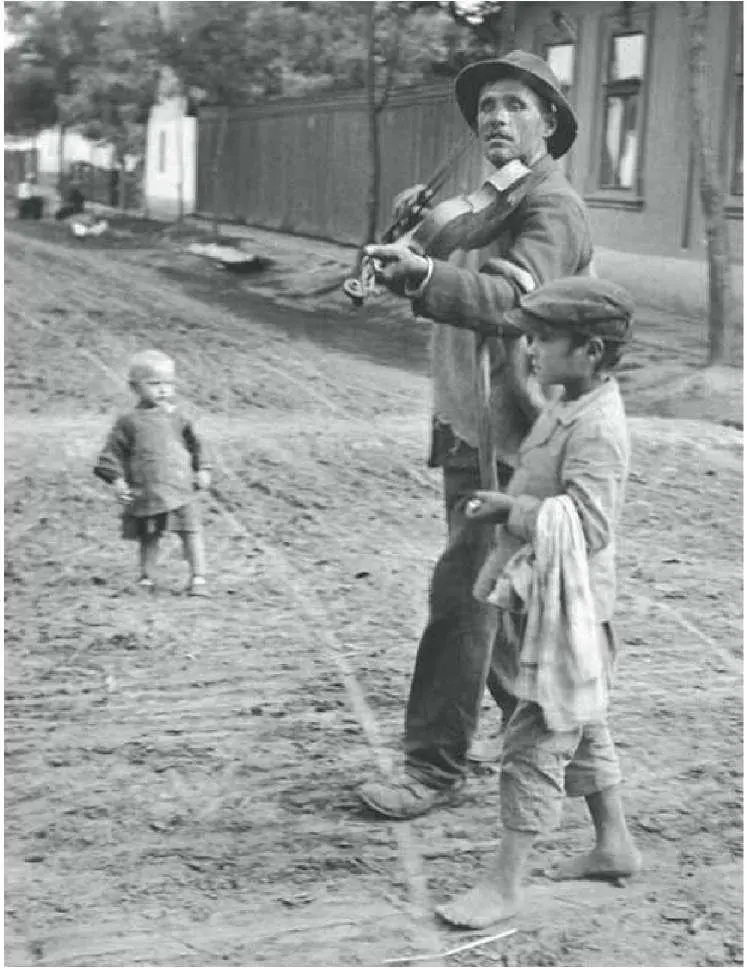

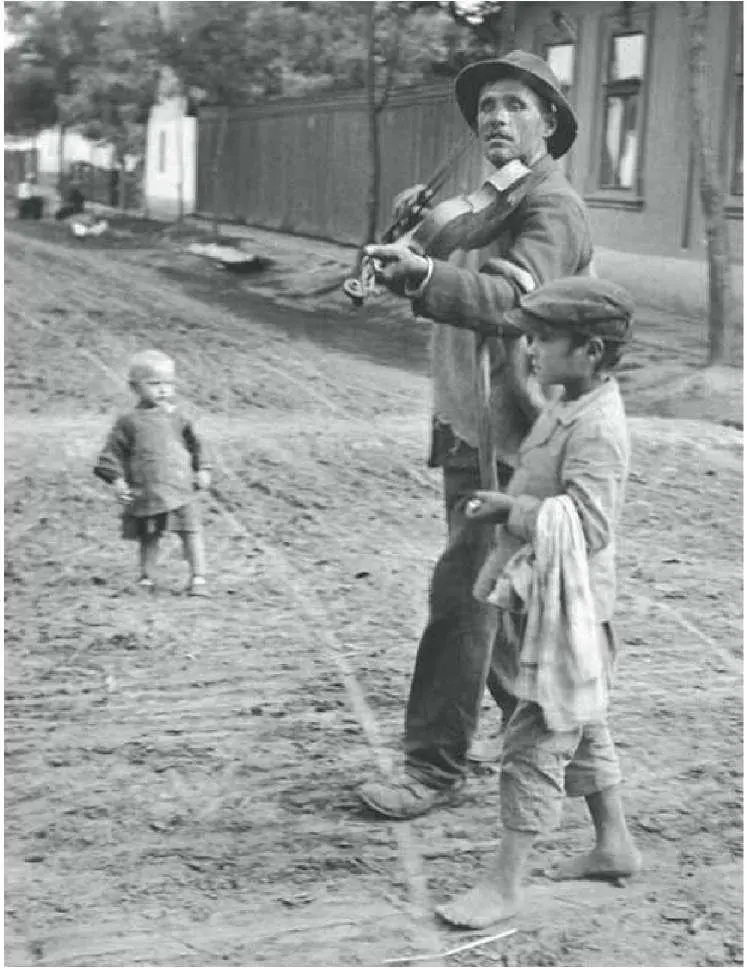

IT'S POSSIBLE THAT everything I've written so far began with this photograph. The year is 1921, in a small Hungarian town, Abony, seven kilometers west of Szolnok. A blind violinist crosses the street, playing. He is led by a barefoot boy wearing a visored cap, a boy in his early teens. The shoes on the musician's feet are worn, broken. His right foot at the moment rests on a narrow track made by a cart's iron wheel. The street is unpaved. The ground must be dry: the boy's feet are not muddy, and the tracks are not deep. The tracks arc gracefully to the right and disappear into the blurry depths of the photograph. Along the street, a wooden fence, and part of a house is visible — a reflection of sky in its window. Farther on stands a white chapel. Trees grow behind the fence. The musician's eyes are shut. He walks and plays, for himself and for the unseen space around him. Besides these two pedestrians on the street is a child of a few years. He is turned toward them but looks beyond, as if there is something of greater interest following them outside the frame. It's a cloudy day, because neither people nor things cast a sharp shadow. On the violinist's right arm (so he's left-handed) hangs a cane, and on the guide's arm what appears to be a small blanket. Only a few steps separate the two from the edge of the photograph. They'll be gone in a moment, and the music with them. Leaving only the toddler, the road, and the wheel tracks.

For four years I have been haunted by this picture. Wherever I go, I seek its three-dimensional, color equivalent, and often seem to find it. That's how it was in Podoliniec; in the side streets of Lewoczy; in white-hot Gönc, where I was looking for a train station, which turned out to be an empty, ruined building, and no train departed until the evening. That's how it was in Vilmány, on an empty platform amid vast fields melting in the heat; how it was at the marketplace in Delatyn, where old women sold tobacco; how it was in Kwasy, when the train had already left and there was not a soul in sight, though the houses stood close together. And in Solotvino, among the dead mine shafts covered with salt dust, and in Dukla, when a heavy, tedious wind blew from the mountain pass. In all these spots, in 1921, André Kertész put his stamp on the transparent screen of space, as if time had halted then and the present was revealed to be a misunderstanding, joke, or betrayal, as if my appearance in these various locations was an embarrassing anachronism, because I came from the future, but was no wiser for that, only more afraid. The space of this photograph hypnotizes me, and all my traveling has had only one purpose: to find, at long last, the secret passage into its interior.

Читать дальше