Andrzej Stasiuk

On the Road to Babadag

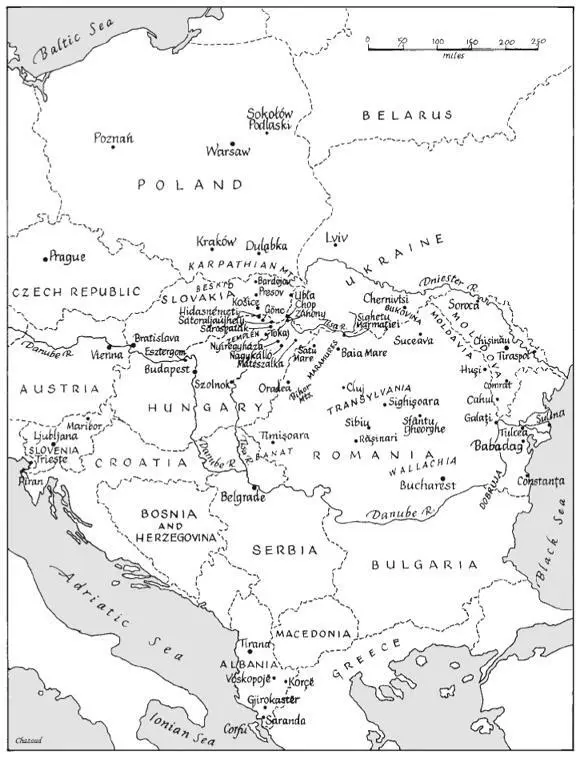

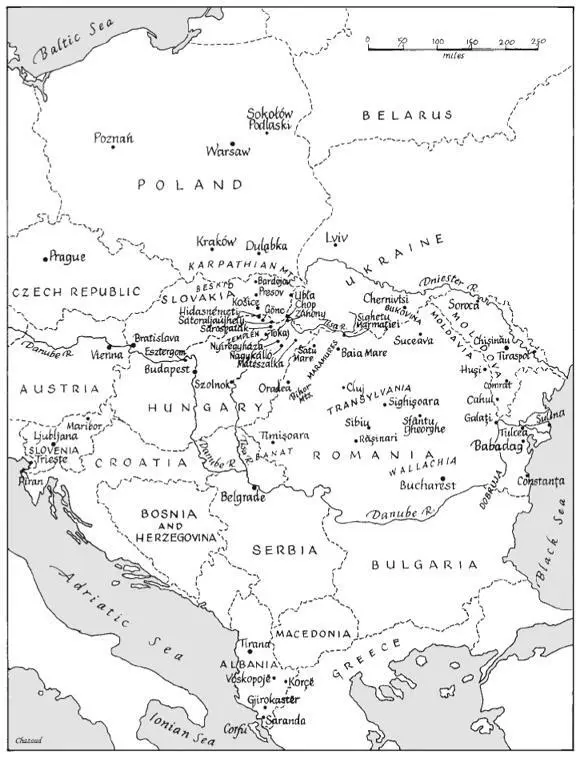

YES, IT'S ONLY that fear, those searchings, tracings, tellings whose purpose is to hide the unreachable horizon. It's night again, and everything departs, disappears, shrouded in black sky. I am alone and must remember events, because the terror of the unending is upon me. The soul dissolves in space like a drop in the sea, and I am too much a coward to have faith in it, too old to accept its loss; I believe it is only through the visible that we can know relief, only in the body of the world that my body can find shelter. I would like to be buried in all those places where I've been before and will be again. My head among the green hills of Zemplén, my heart somewhere in Transylvania, my right hand in Chornohora, my left in Spišská Belá, my sight in Bukovina, my sense of smell in Răşinari, my thoughts perhaps in this neighborhood… This is how I imagine the night when the current roars in the dark and the thaw wipes away the white stains of snow. I recall those days when I took to the road so often, pronouncing the names of far cities like spells: Paris, London, Berlin, New York, Sydney… places on the map for me, red or black points lost in the expanse of green and sky blue. I never asked for a pure sound. The histories that went with the cities, they were all fictions. They filled the hours and alleviated the boredom. In those distant times, every trip resembled flight. Stank of panic, desperation.

One day in the summer of '83 or '84, I reached Słubice by foot and saw Frankfurt across the river. It was late afternoon. Humid blue-gray air hung over the water. East German high-rises and factory stacks looked dismal and unreal. The sun was a dull smudge, a flame about to gutter. The other side — completely dead, still, as if after a great fire. Only the river had something human about it — decay, fish slime — but I was sure that over there the smell would be stopped. In any case I turned, and that same evening I headed back, east. Like a dog, I had sniffed an unfamiliar locale, then moved on.

I had no passport then, of course, but it never entered my head to try to get one. The connection between those two words, freedom and passport, sounded grand enough but was completely unconvincing. The nuts and bolts of passport didn't fit freedom at all. It's possible that there, outside Gorzów, my mind had fixed on the formula: There's freedom or there isn't, period. My country suited me fine, because its borders didn't concern me. I lived inside it, in the center, and that center went where I went. I made no demands on space and expected nothing from it. I left before dawn to catch the yellow-and-blue train to Żyrardów. It pulled out of East Station, crossed downtown, gold and silver ribbons of light unfurling in the windows. The train filled with men in worn coats. Most got off at the Ursus factory and walked toward its frozen light. Dozens, hundreds, barely visible in the dark; only at the gate did the mercury light hit them, as if they were entering a huge cathedral. I was practically alone. The next passengers got on somewhere in Milanówek, in Grodzisk, more women in the group, because Żyrardów was textiles, fabrics, tailoring, that sort of thing. Black tobacco, the sour smell of plastic lunch bags mixed with the reek of cheap perfume and soap. The night came free of the ground, and in the growing crack of the day you could see the huts of the crossing guards, who held orange caution flags; cows standing belly-deep in mist; the last, forgotten lights in houses. Żyrardów was red, all brick. I got off with everyone else. I was shiftless here, but whatever I did was in tribute to those who had to get up before the sun, for without them the world would have been no more than a play of color or a meteorological drama. I drank strong tea in a station bar and took the train back, to go north in a day or two, or east, without apparent purpose.

One summer I was on the road seventy-two hours nonstop. I spoke with truck drivers. As they drove, their words flowed in ponderous monologue from a vast place — the result of fatigue and lack of sleep. The landscape outside the cabin window drew close, pulled away, to freeze at last, as if time had given up. Dawn at a roadside somewhere in Puck, thin clouds stretching over the gulf. Out from under the clouds slipped the bright knife edge of the rising day, and the cold smell of the sea came woven with the screech of gulls. It's entirely possible I reached the beach itself then, it's entirely possible that after a couple of hours of sleep somewhere by the road a delivery van stopped and a guy said he was driving through the country, north to south, which was far more appealing than the tedium of tide in, tide out, so I jumped on the crate and, wrapped in a blanket, dozed beneath the fluttering tarp, and my doze was visited by landscapes of the past mixed with fantasy, as if I were looking at things as an outsider. Warsaw went by as a foreign city, and I felt no tug at my heart. Grit in my teeth: the dust raised from the floorboards. I crossed the country as one crosses an unmapped continent. Between Radom and Sandomierz, terra incognita. The sky, trees, houses, earth — all could be elsewhere. I moved through a space that had no history, nothing worth preserving. I was the first man to reach the foot of the Góry Pieprzowe, Pepper Hills, and with my presence everything began. Time began. Objects and landscapes started their aging only from the moment my eye fell on them. At Tarnobrzeg I rapped on the sheet metal of the driver's cabin; impressed by the size of a sulfur outcrop, I wanted him to stop. Giant power shovels stood at the bottom of a pit. It didn't matter where they came from. From the sky, if you like, to bite into the land, to chew their way into and through the planet and let an ocean surge up the shaft to drown everything here and turn the other side to desert. The stink of inferno rose, and I could not tear my gaze from the monstrous hole that spoke of the grave, piled corpses, the chill of hell. Nothing moved, so this could have been Sunday, assuming there was a calendar in such a place.

This sequence of images was not Poland, not a country; it was a pretext. Perhaps we become aware of our existence only when we feel on our skin the touch of a place that has no name, that connects us to the earliest time, to all the dead, to prehistory, when the mind first stood apart from the world, still unaware that it was orphaned. A hand stretches from the window of a truck, and through its fingers flows the earliest time. No, this was not Poland; it was the original loneliness. I could have been in Timbuktu or on Cape Cod. On my right, Baranów, "the pearl of the Renaissance," I must have passed it a dozen times in those days, but it never occurred to me to stop and have a look at it. Any place was good, because I could leave it without regret. It didn't even need a name. Constant expense, constant loss, waste such as the world has never seen, prodigality, shortage, no gain, no profit. The morning on the coast, Wybrzeże, the evening in a forest by the San River; men over their steins like ghosts in a village bar, apparitions frozen in mid-gesture as I watched. I remember them that way, but it could have been near Legnica, or forty kilometers northeast of Siedlec, and a year before or after in some village or other. We lit an evening fire, and in the flickering light, young guys from the village emerged; probably the first time in their lives they were seeing a stranger. We were not real to them, or they to us. They stood and stared, their enormous belt buckles gleaming in the dark: a bull's head, or crossed Colt revolvers. Finally they sat near, but the conversation smacked of hallucination. Even the wine they brought couldn't bring us down to earth. At dawn they got up and left. It's possible that a day or two later I stood for ten hours in Złoczów, Zolochiv, and no one gave me a lift. I remember a hedgerow and the stone balustrade of a little bridge, but I'm not sure about the hedgerow, it could have been elsewhere, like most of what lies in memory, things I pluck from their landscape, making my own map of them, my own fantastic geography.

Читать дальше