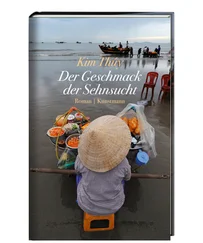

The alleys were swarming with children skipping, with ropes braided out of hundreds of multicoloured rubber bands. My favourite toy wasn’t a doll that said, “I love you.” My dream toy was a small wooden chair with a built-in drawer where the street vendors kept their money, and also the two big baskets they carried at either end of a long bamboo pole balanced on their shoulders. These women sold all kinds of soups. They walked between the two weights: on one side, a large cauldron of broth and a coal fire to keep it hot; on the other, the bowls, chopsticks, rice noodles and condiments. Sometimes the vendor might even have a baby hanging from her back. Each merchant advertised her wares with a particular melody.

Years later, in Hanoi a French friend of mine would get up at five in the morning to record their songs. He told me that before long those sounds would no longer be heard on the streets, that those strolling merchants would give up their baskets for factory work. So he would safeguard their voices reverently and ask me to translate them along the way, then he would list them by category: merchants selling soup, selling cream of soya, buyers of glass for recycling, knife-grinders, masseurs for men, bread-sellers … We spent whole afternoons working on translations. With my friend, I learned that music comes from the voice, the rhythm and the heart of each person, and that the musicality of those unrecorded melodies could lift the curtain of fog, pass through windows and screens to waken us as gently as a morning lullaby.

He had to get up early to record them because the soups were sold mainly in the morning. Each soup had its own vermicelli: round ones with beef, small and flat with pork and shrimp, transparent with chicken … Each woman had her specialty and her route. When Marie-France, my teacher in Granby, asked me to describe my breakfast, I told her: soup, vermicelli, pork. She asked me again, more than once, miming waking up, rubbing her eyes and stretching. But my reply was the same, with a slight variation: rice instead of vermicelli. The other Vietnamese children gave similar descriptions. She called home then to check the accuracy of our answers with our parents. As time went on, we no longer started our day with soup and rice. To this day, I haven’t found a substitute. So it’s very rare that I have breakfast.

I went back to having soup for breakfast when I was pregnant with my son Pascal, in Vietnam. I didn’t crave pickles or peanut butter, just a bowl of soup with vermicelli purchased on a street corner. Throughout my childhood, my grandmother forbade us to eat those soups because the bowls were washed in a tiny bucket of water. It was impossible for the vendors to carry water on their shoulders as well as the broth and the bowls. Whenever it was possible, they would ask people for some clean water. As a small child, I often waited for them at the fence near the kitchen door with fresh water for their buckets. I would have traded my blue-eyed doll for their wooden chairs. I should have suggested it, because today they’ve been replaced by plastic chairs, which are lighter, don’t have a built-in drawer, and don’t show the traces of fatigue and wear in their grain as wooden benches do. The merchants stepped into the modern era still carrying the weight of the yoke on their shoulders.

The trace of the red and yellow stripes of a Pom sandwich-bread bag is burned into one side of our first toaster. Our sponsors in Granby had placed that small appliance at the top of the list of essentials to buy when we moved into our first apartment. For years we lugged that toaster from one place to the next without ever using it, because our breakfast was rice, soup, leftovers from the night before. Quietly, we started eating Rice Krispies, without milk. My brothers followed this with toast and jam. Every morning for twenty years, without exception, the youngest breakfasted on two slices of sandwich bread with butter and strawberry jam, no matter where he was posted — New York, New Delhi, Moscow or Saigon. His Vietnamese maid tried to make him change his habits by offering him steaming balls of sticky rice covered with freshly grated coconut, roasted sesame seeds and peanuts crushed in a mortar, or a piece of warm baguette with ham spread with homemade mayonnaise, or pâté de foie decorated with a sprig of coriander … He brushed them all aside and went back to his sandwich bread, which he kept in the freezer. During my latest visit to him I discovered that he keeps our old stained toaster in a cupboard. It’s the only trinket he has carted with him from country to country as if it were an anchor, or the memory of dropping the first anchor.

I discovered my own anchor when I went to meet Guillaume at Hanoi airport. The scent of Bounce fabric softener on his T-shirt made me cry. For two weeks I slept with a piece of Guillaume’s clothing on my pillow. Guillaume, for his part, was dazzled by the scent of jackfruit, kumquats, durians, carambola, of bitter melons, field crabs, dried shrimp, of lilies, lotus and herbs. Several times he went to the night market where vegetables, fruit and flowers were traded back and forth between the baskets of the vendors negotiating among themselves in a noisy but controlled chaos, as if they were on the floor of the Stock Exchange. I would go to this night market with Guillaume, always with one of his pullovers over my shirt because I’d discovered that my home could be summed up as an ordinary, simple odour from my daily North American life. I had no street address of my own, I lived in an office apartment in Hanoi. My books were stored at Aunt Eight’s place, my diplomas at my parents’ in Montreal, my photos at my brothers’, my winter coats with my former roommate. I realized for the first time that Bounce, the smell of Bounce, had given me my first attack of homesickness.

During my early years in Quebec, my clothes smelled of damp or of food because after they were washed they were hung up in our bedrooms on lines strung from wall to wall. At night, every night, my last image was of colours suspended across the room like Tibetan prayer flags. For years I inhaled the scent of fabric softener on my classmates’ clothes when the wind carried it to me. I happily breathed in the bags of used clothes we received. It was the only smell I wanted.

Guillaume left Hanoi after staying with me for two weeks. He had no clean clothes to leave me. Over the following months, I received in the mail now and then a tightly sealed plastic envelope with a freshly dried handkerchief inside, smelling of Bounce. The last package he sent me contained a plane ticket for Paris. When I arrived, he was waiting to take me to an appointment with a perfumer. He wanted me to smell a violet leaf, an iris, blue cypress, vanilla, lovage … and, most of all, everlasting, an aroma of which Napoleon said smelled of his country before he even set foot on it. Guillaume wanted me to find an aroma that would give me my country, my world.

I‘ve never worn any other perfume than the one that was created for me at Guillaume’s request during that trip to Paris. It replaced Bounce. It speaks for me and reminds me that I exist. One of my roommates spent several years studying theology and archaeology in order to understand who our creator is, who we are, why we exist. Every night, she came back to the apartment not with answers but with new questions. I never had any questions except the one about the moment when I could die. I should have chosen the moment before the arrival of my children, for since then I’ve lost the option of dying. The sharp smell of their sun-baked hair, the smell of sweat on their backs when they wake from a nightmare, the dusty smell of their hands when they leave a classroom, meant that I have to live, to be dazzled by the shadow of their eyelashes, moved by a snowflake, bowled over by a tear on their cheek. My children have given me the exclusive power to blow on a wound to make the pain disappear, to understand words unpronounced, to possess the universal truth, to be a fairy. A fairy smitten with the way they smell.

Читать дальше