Everything we’ve gone through has changed us a lot. It’s as if we had to mature through blows.

She feels like living faster.

I want to caress and be caressed.

We want to be set free, she says, while filling a glass of grappa for me. Grappa is a drink just like pisco or brandy. But of course it’s Italian. The bottle looks like a glass sculpture. The label reads GRAPPA MORBIDA.

It burns.

Che suggests that I stop by a pharmacy to buy rubbers. I’m not sure if I want that. I mean, I want to know what she’s like. I want to feel her. And a rubber … Maybe I’m thinking like an idiot. I’ll do whatever Patricia Bettini decides.

At the terminal, a voice announces that the next bus to Valparaíso will leave in ten minutes. The driver reads La Cuarta with his legs stretched out. The air from a small fan makes the pages of the newspaper shake. I take a look inside the bus, but I don’t see Patricia.

I join the passengers saying good-bye to their relatives on the platform. A loader puts an old trunk in the luggage storage. He wears a headband with the drawing of a rainbow.

I fear that Patricia has changed her mind. For girls, the decision to make love for the first time is like something from a Greek tragedy. Or at least from a soap opera. They put so many things into their heads, both at home and school, that then they go through life walking on their tiptoes, trying not to break eggs.

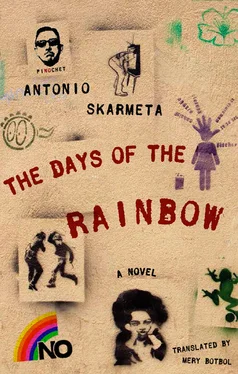

And they’re right. Love always leaves a mark on them. Even scars. That’s why it’s weird that Patricia Bettini has decided to be with me. We still have two months left before finishing high school. And Pinochet still has to call for free elections. That will take some time. Like one year, I think. She said to me, “I want to be with you, intimately.”

But not in Santiago.

Santiago is the school, the church, Don Adrián’s unemployment, the cars without license plates in front of her house, the tear-gas bombs, Professor Paredes’s absence.

She wants me to understand.

It’s fine. To me, loving her is not a matter of geography. Although I’m the least romantic guy on earth, I also like a place where the eye isn’t always bumping into buildings and TV antennas.

I feel like being near the sea.

A sea to see her. Valparaíso.

But me, what’s really me is downtown Santiago. I’m thrilled that the developers didn’t knock down the colonial church and that they had to create a detour in the Alameda to preserve it.

“That’s the way to treat a lady,” Professor Santos said.

When they first announced that it would be demolished, my dad and I went out into the streets to protest along with the Franciscan priests.

My daddy delivered a speech near the fountain in the Pergola of Flowers.

He said that the church was the humble and sweet Francis of Assisi and the government of Pinochet was the wolf.

“Gubbio’s wolf,” *he said.

I don’t know where he gets those ideas.

He’s bad at keeping quiet.

But he barely allows me to breathe.

So the cops came. First, they threw just a little bit of water at us. One gets used to their water. In the worst case situation, if the hose stream is too strong, it may push you against a wall and you may break your head. The best thing to do is to throw yourself to the ground.

So they can soak you. So they can leave you there drenched like a dog.

Professor Paredes used to say, bending down under the stream, “Relax and enjoy it.”

Tear-gas bombs are a different matter. If one explodes in your face, you can end up blind.

But I’ve given all my life to downtown Santiago. Eighteen years. Lastarria Street. Villavicencio. The soda stands, with the vendor girls, with as much makeup as cabaret dancers.

Now the driver shouts that the bus will leave in three minutes.

I squeeze the hundred-peso coins I have in my pocket and try to see if there’s a pay phone nearby.

Right at that moment, Patricia Bettini shows up.

And as she comes closer, running toward me, I feel my heart pumping stronger than ever.

It seems as if she’s becoming smaller and slimmer inside my hug. Her brown hair falls loose on her shoulders and there’s not a trace of the school discipline of bobby pins, headbands, and clips that she uses to prevent her hair from flooding over her face.

Today she’s not wearing the school uniform.

She has on a tight red polo shirt, one size too small.

Her breasts protrude under the fabric, and she’s showing cleavage.

Embellished with furious red lipstick, her lips perfectly match her shirt. It’s a mouth screaming, “Kiss me, bite me.” I swallow. I scratch her cheek with the few hairs that have sprouted in my chin. I breathe in deeply the smell of her skin. The aroma of tropical fruit from her hair gel makes me dizzy.

“Are you ready?” she asks.

She wants to know if I’m ready. I’ve set out on this flight. I live in the country of the No , and every one of my nerves knows that nobody will ever take it away from me. I feel it in the pulse of my wrists, in my temples, beating riotously.

In my erection.

Shoot! Democracy is so erotic!

“I’m ready,” I say, only to not say all that’s unutterable.

She puts the ticket in my shirt pocket and then touches my forehead with two fingers, like a doctor who needs to check if you have a fever.

“Then, Nicomachus Santos, your tickets to Valparaíso!”

*Gubbio is a medieval town in Umbria, where it is said that St. Francis tamed the wolf that terrorized its inhabitants.

PATRICIA BETTINIshows Nico Santos the notebook with a blue cover where her father was writing his notes for the No campaign.

A horse canters in the prairie; it’s the horse of freedom.

A cab’s windshield wipers move; it’s the No of freedom.

A heart pumps, systole and diastole; it’s the rhythm of freedom.

An old lady buys a tea bag at Don Aníbal’s store; it’s the tea of freedom.

A policeman hits a student on his head; it’s the hour of freedom. Song:

I don’t want him, Daddy; I don’t want him, Mommy; I don’t want him in English, or in Mapudungun; or in tango; or in bolero; or in fox-trot; or in cumbia or chachacha; I don’t want him; I don’t want him. What I want is freedom.

Christopher Reeve is in Chile. Film him — he came to protect the actors who have received death threats. Have him say something. Something like—“Okay, folks, you’re right, remember that the vote is secret and that Chile being a free country depends on you.”

Bravo, Superman; in English, he speaks of freedom.

Film Jane Fonda. I don’t know where you may find her, but I heard her saying on the radio—“During all these years, the pain of Chile has been our pain, now the future of Chile is in your hands.”

Let’s include Jane with the boots song—“These boots are made for walking, and they will walk all over you; walk, boots; walk over Pinochet; walk, walk, walk, walk — toward liberty.”

And let’s use some cueca—“Tiquitiquití, tiquitiquitá, you say ‘no’ and freedom will light up.”

And do not forget Violeta *—it gave me the alphabet, and with it the words that I think and declare; it gave me the “N” and gave me the “O”; it gave me the freedom to say “No.”

They broke his hands, they fractured his femur; he was shot seventy-two times; they punched his belly. Freedom hurts. (No need to say whom we’re talking about; everybody knows; it’s better if people react by themselves.)

Читать дальше