"It grows on all of us."

"Disgusting."

"You like to have it on your head, don't you?"

He put his hand on her shoulder and guided her to the mirror over the sink. They looked at their images: she was pale and old, he was smooth and young. She had not colored her hair in some time-since Beth, he guessed-and gray was woven through the yellow. He tried to keep his gaze on her worn features but it was hard and he was drawn back to his own reflection.

"See? It's good to have hair on your head," he said. "Isn't it? You wouldn't want to be bald."

"It should stay there, then," she said uncertainly. "It shouldn't fall off everywhere. It gets in the cracks. It sticks on things. It even gets on your tongue. Then you can't get it out! You can't even find it with your fingers. It's a finger tricker."

She was growing agitated.

"It's OK," he said. "Don't worry."

"It goes down your throat and makes you choke and throw up.

"You've been swallowing it?"

"Not on purpose," she said, indignant.

"Good. I'm glad to hear that."

"But it grows in the dark."

"At night, you mean?"

"In the body cracks. Under the arms. In the crotchal region.

He looked at her again. So much of composure, which he had till now believed to be a process of physical assembly, was in fact internal. His mother's hair had been combed, her face was clean, and yet she was dissolving. It was clearly visible.

"It also grows in the light," he said softly. "On the top of the head. Right? The stin shines right down on it. And on the legs and arms."

She cocked her head, considering.

"Let me run you a warm shower. Can I do that? Then I'll give you some privacy and you can get in."

In the kitchen he talked to Vera, keeping his voice low.

"Listen," he urged, helpless. "Maybe a specialist could help her. A neurologist? I'll make calls. I mean she's not even sixty."

"She still goes to church," said Vera. "Almost every day. She is not unhappy"

They turned to see his mother standing in the hallway, fully dressed but soaking. Her clothes dripped onto the floor. She had a comb in each hand.

Walking back to his apartment he tried to enumerate family members and came up with almost none. His father's parents had died before he had time to form a memory of them, his mother's mother had died when his mother was a small child, to be replaced by a stepmother who left again when his mother was only twelve, and his mother's father, the cranky Ukrainian who was the only grandparent he could remember, had died a few years back of cancer… aunts and uncles were estranged or distant. He had met a couple of them when he was a boy or a teenager, but they had fallen away after. The few cousins he had he would not even recognize if he passed them.

His father had never seemed to remember the family he'd grown up with, never seemed to think of them-as though it was usual and correct to move ahead and leave brothers and sisters behind you, unnoticed. His mother had tried to encourage visits, he recalled vaguely, had sent Christmas cards and gifts to his aunts and uncles and cousins until possibly they stopped acknowledging them.

Part of the growing estrangement from family, in the end, was a simple product of freedom. It was the American way to pick and choose from a range of possibilities, not to be bound and obligated. Cut loose from a certain idea of duty, it turned out, individuals did no great deeds but only drifted apart.

Women left. There was a general feeling, he thought, a preconception that men were the leavers, but in fact according to statistics men rarely left. Mostly the leaving was done by women. But it was men who drove them to it; it was the men who misbehaved.

With each mammal it was different, with each bird, reptile, amphibian, fish and invertebrate, but in the main it was the males who went out, wandered, ventured, and were exposed. They traveled further, died faster, and did not raise the young. Meanwhile the females stayed. The females stored up fat for lean times and lay low, in the hive, in the den, in the nest, in the web. In the sandy hollow. Mostly the females stayed, the males strayed, and so on down through the years. In the wild the males were more showy; they strutted and preened and the dull ones died off and the others fathered sons with magnificent plumage.

But among modern Americans, he had read in a magazine in his dentist's waiting room, three-quarters of divorces were instigated by women. More men betrayed their wives than vice versa: but finally it was the women who removed themselves, who went away completely, when it came to humans. In his case it was true, anyway-first her, then her, and even her. All left him in the end, whether by death or choice or defect. He couldn't blame them. They were otherwise occupied, or they were hurt.

Of course his father had left before anyone else, that was also true. His father was a man, and he had left both of them. But by his own admission his father had never been there in the first place.

The zoos were not new. What was new about them was the way the animals were valued as possessions more than symbols, the way the animals had become scarcer and scarcer as millennia passed so that they now were tradable. There had been zoos for thousands of years, for almost as long as there had been men who wanted to show their power through the jewels of their collections. More than two thousand years before Christ there had been, in the Sumerian city of Ur, vast collections of thousands of animals, gifts to the kings from their subjects-goods already, maybe, though still ripe for slaughter. Tuthmosis III let his wild trophies pace the gardens of the temple of Karnakcheetahs, monkeys, deer and antelope with curling extravagant horns.

He thought of these ancient zoos as he slept in the new ones, so that some nights he was almost in both of them.

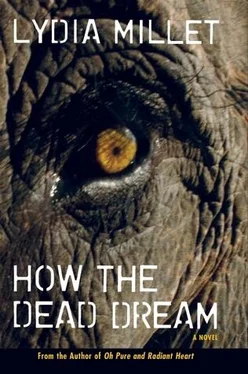

These days the zoos were full of final animals. Almost all primates were on their way out, almost all the large carnivores, the great cats and wild dogs and the bears, almost all the wide-ranging and large herbivores, giraffes and pachyderms, almost all the vast, intelligent mammals that lived in the oceans. They were all on the clock, in the long moment of going before being gone. The zoos were a holding pen: they had the appearance of gardens, the best of them, but they were mausoleums.

A child might believe a zoo was a small paradise-to a child it might look like an Ark of creatures, in all their splendid forms. When he went to a zoo by daylight, a visitor like everyone else, he watched the children watching the animals. He saw their captivation. Why should it not resemble an Ark to them? In an Ark the animals were orderly, after all, walking neatly in pairs and, for the purpose of their salvation, submitting politely to the will of men.

The parents reassured each other and they reassured the children. Here animals were separate from the hazard of each other, their predators and their prey. They were safe from men too, for in the wild there was always also the ruin of the wild-new roads, earth-moving machines and fire and chemicals that stripped the leaves off forests. Here the animals were safe from everything but old age. It was widely known that they lived longer in captivity.

In fact whole species were being protected as living relics, given the honor of being almost extinct. This status was posted on their exhibitions sometimes, as though it was a blue ribbon. But even when the animals were relics they were less the last of their kind than a different kind entirelya hybrid kind, he thought. A zoo kind. It had been observed since the nineteenth century that the mental fitness of zoo animals was seldom attended to by the zoo authorities, and this persisted. Where the large and wide-ranging animals were concerned, more often than not there was little to find there besides illness. Long ago they had lost everything and gone mad.

Читать дальше