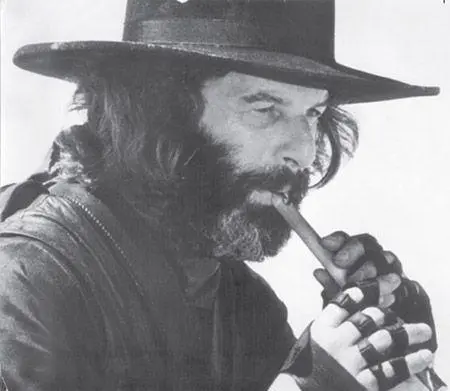

Although I devoted most of my time to filming, creating movies such as Fando y Lis, El Topo, The Holy Mountain, and Santa Sangre —an activity that gave me experiences that would require a whole book — I also continued developing the art of theatrical advice. I established a series of acts to perform in a given time: five hours, twelve hours, twenty-four. It was a program developed as a function of the problem brought in by the patient, aimed at breaking the character with which he had identified in order to help him restore ties with his profound nature. “Whoever is depressed, delusional, or failing, that is not you.” To an atheist, I assigned the task of taking on the personality of a saint for some weeks. To a woman who suffered from a hatred of her children, I assigned the duty — in a written contract, signed with a drop of her blood — of imitating motherly love for a hundred years. To a judge, concerned with the power he held to punish in the name of a law and a morality that he doubted, I assigned the task of dressing up as a vagrant to go begging in front of the terrace of a restaurant while taking handfuls of dolls’ eyes out of his pockets. To an unhealthily jealous man of questionable virility I assigned the task of showing up at a family reunion dressed as a woman.

In this manner I created, overlaid on the personality, a person intended to visit everyday life and make it better. At this point my theatrical quest was acquiring a therapeutic dimension. I transformed myself from writer and director into an adviser, instructing people in order that they might free themselves from their personalities and conduct themselves as authentic beings in the comedy that is existence. The route I offered them was that of imitation. Gone was the inexpert youth who, believing himself to be imitating civil holiness, had sexually exploited a poor young woman. Now the process was based on a real desire to change.

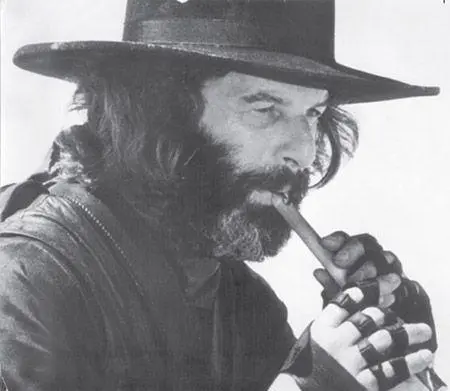

Converted into a film actor in El Topo.

The character transforms violence into (musical) art.

If a good Catholic practiced the imitation of Christ, why shouldn’t an atheist who is tired of his disbelief begin to imitate a priest? Why shouldn’t a weak man, feeling impotent, imitate virile strength by painting his testicles red? Why shouldn’t a woman, raised as a boy by her family, overcome her sterility by sticking a pillow under her dress to imitate pregnancy? I myself, imitating what I needed most — faith — realized how far I was from believing in God, in human beings, or in anything at all. I doubted art. What was it for? If it was to entertain people who were afraid of waking up, I was not interested in it. If it was a means of succeeding economically, I was not interested. If it was an activity taken on by my ego to exalt itself, I was not interested. If I had to be the jester for those in power, those who poison the planet and leave millions of people starving, I was not interested. What then was the purpose of art? After a crisis so profound that it led me to think of suicide, I arrived at the conclusion that the purpose of art was to heal. “If art does not heal, it is not art,” I told myself, and I decided to unite my artistic and therapeutic activities. I do not wish to be misunderstood: the only therapy I had known was carried out by scientific minds, confronting the chaotic subconscious and trying to bring order to it, extracting a rational message from dreams. I approached therapy not as science, but as art. My goal was to teach reason to speak the language of dreams. I was not interested in art turned into therapy, but in therapy converted into art.

I owe this profound entry into the expression of the unconscious force — which, if we listen to it, is not our enemy but our ally — to Ejo Takata, who was my Zen master for a period of five years. Without really knowing what I was getting into, I agreed to be part of a group that meditated for seven full days, sleeping only twenty minutes each night. Full of courage, I knelt with my buttocks supported on a cushion, crossed my hands, put my thumbs together with minimal precision as if I were holding a cigarette paper between them, stretched out my spine, felt myself anchored in the ground and united to the center of the Earth while my skull reached up toward the sky, relaxed my face and then the rest of my muscles, eliminated all words and feelings from my mind, and, believing my technique to be perfect, prepared to remain there motionless, like Buddha, for a week. After barely two hours, the torture began. My knees, legs, back, and entire body hurt. If I moved just a little, the giant Mexican patrolling with his baton would give me a hiding on the shoulders. If I winced when flies walked on my face, the master would yell demonically. My imagination flared up, and so did my anger. What was I doing here, suffering needlessly in the midst of these enlightened shaved heads? I saw my shoes in a corner, like open mouths, inviting me to fill them and leave this hell. At the sound of a gong, we had to run to the dining room and gobble down a bowl of rice, almost boiling hot, in two minutes, without leaving a single grain in the bowl. We returned to meditate with bloated bellies. A concert of belches and continuous farting began. With anger and shame I noticed that the others, especially the women, were holding it in better than I. At midnight we lay down like dogs to sleep on the floor for those divine twenty minutes. We awoke to screams and insults and had to run to sit and continue our meditation. We were allowed to go and defecate once a day in a communal latrine, where a row of holes over an artesian well invited men and women alike to completely give up privacy. I resisted and resisted, out of pride rather than mysticism. Takata began playing the drum, singing the Heart Sutra. Luz María, a chunky lesbian in front of him who also was playing the drum, flew into a rage and threw her instrument at his head. The monk made a minimal movement, ducking by a few centimeters so that the heavy instrument passed millimeters from his ear and smashed into the wall, leaving a hole. Ejo, not in the least perturbed, kept chanting the Sutra. No comment was made about this assault.

By the fifth day I had become a scarecrow. My knees were swollen and bloody, my belly was full of gas, my eyes were tear filled, and there was a pain in my chest. At three in the morning, I was dragged by two aggressive students to a room where the master was going to give me a riddle, a koan. I was forced to fight and defend myself as the fanatical pair rained blows on me. I crept down the stairs and sat in front of the curtain hiding the sacred room.

“My chest hurts,” I said. “I think I’m going to have a heart attack.”

“Break yourself!” they replied, and left.

A gong sounded, indicating that I should go in. And so I did. There was Ejo, transfigured, dressed in a ceremonial robe that made him look like a saint. He looked at me with an objectivity that I construed as contempt and said to me as I knelt before him with my forehead touching the floor, “It does not begin, it does not end. What is it?”

I had been prepared to respond to a classic riddle, “This is the sound of two hands clapping, what is the sound of one hand clapping?” to which I would have raised my open right hand, answering with a broad smile, “Do you hear?” Or, “Does a dog have Buddha nature?” to which I would have responded by screaming, “Mu!” But when asked this question, so simple, so ingenuous, so obvious, I could only stammer, “Ejo, what do you want me to say? God? The universe? Me? You? All of this?” The monk took up a hammer and hit the gong, signaling for all the zendo *5to hear that I had failed. I bowed, humbled, and began to leave. Then Ejo yelled, “Intellectual, learn to die!” These words, spoken in an atrocious Japanese accent, changed my life. Suddenly, I realized that all my searching up to that point, everything that I had done, had been carried out by a cowardly intellect that, afraid to die, was clinging to the iron bars of reason. Existence began when the actor-self stopped identifying with the observer-self. In a flash, I entered the world of dreams.

Читать дальше