There was no conversation on the journey. The leather helmets and the roaring engine made it impossible. They’d stopped for gas twice, though, at unattended pumps in gated maintenance stations deep in the national forest. At the first one of these, both men took off their helmets and drank from a canteen.

“It’s Tessa Bright, isn’t it?” asked Mark. “Your Bluebird asset.”

“She’s our most valuable one, yes,” said Swain. He was running a handkerchief around his dirty neck.

Mark had known a lesbian attorney for an evil cabal would never smoke Lucky Strikes.

And at the second stop, leaning on the bumper of the car and wishing for a cigarette, Mark asked Swain, “So you postal guys are really the last uncorrupted law enforcement in the U.S. government?”

“Last uncorrupted intelligence agency,” Swain clarified. “Pope hasn’t turned the Forest Service yet.” He clunked the nozzle back into the gas pump and replaced the little padlock that prevented its use.

Mark thought he could see something on the horizon, a black mote against the deep blue. Was it coming closer? He stepped out from behind his boulder and walked nearer the lapping shore. He still couldn’t tell whether the speck was approaching. Why had this chance been offered him? To change course midlife, to earn back his friends, to strike a blow for someone other than himself. The speck resolved itself. It was an inflatable boat, a Zodiac, coming in at high speed. He could hear the whine of its engine now and see a little green light blinking on a tiny mast at its stern.

Look, Ma. While you still can. The greater good of the world is partly dependent on my unhistoric act. You will be proud.

The craft was a hundred feet out now, riding the swells. Mark tried to make out the driver or captain or whatever. It slowed and eased close to the shore, its engines bass and throaty. And then he saw that what he’d thought was the captain was actually just the little pilot station and steering-wheel platform. There was no one at the helm of the craft.

His Node vibrated in his pocket. He fished it out and read its glowing screen: Board the Zodiac, Mark. Dinner awaits. James.

If this goes wrong, he thought, I will deffo rest in an unvisited tomb .

With each step Mark took nearer the water, the wet sand pulled with more force on his bloated shoes. He stepped out of them, rolled the cuffs of his pants, and walked into the lapping waves. Come in. The water’s fine, Lola had said. His legs went quickly numb as he waded out, the cold sending a plume of clarity up his body and into his head. His pants were soaked to midthigh by the time he was able to heave himself onto the black raft. For a moment he lay on its rigid floor, catching his breath and looking up at the first few stars in the east. The grandest mystery, strung over our heads every night. There was the North Star. And there, still faint, was the Big Dipper. The handle of the Big Dipper makes an arc, his dad had taught him long ago. Follow that arc to a star called Arcturus. Arc to Arcturus .

RIP, Pops, he thought, for the first time without bitterness. You will be proud also . Mark would get to write his great work, but maybe only on his heart, and for an audience of one.

He took stock. There was a tall ergonomic pilot’s chair behind the little helm, a sort of neoprene blanket or cape folded on its seat. He stood up, wrapped himself in the blanket. He had to brace himself against the seat behind him as the craft executed a one-eighty, throttled up, and pointed into the horizon. The little boat barreled into the sea, thwacking occasionally into opposing swells. After a minute, Mark looked back. America was a gray humped shape below the new night. He was calm, full of self and secrets, but now with something else as well.

Let’s see. There were those very early readers, Christine Monk and Layla O’Mara, both of whom said don’t stop keep going. Then there was Monica McInerney, who dashed up Arklow Street to say don’t stop keep going, and who put me on to the canny and forthright literary agent Gráinne Fox, who has led me through some strange woods. There was the dynamic duo of Miranda Driscoll and Feargal Ward, friends and co-battlers and twin pillars of The Joinery — that mad, true place in Arbour Hill. There were my other mates there, all of us just tipping away, forging in our smithies. And the Lilliputians downstairs, who kept me bright-eyed and pacing. There was David Mitchell, who told me about helmets. Thank you to the Paul and Amy Foundation, off the South Circular. They made room for us, big time. Also many thanks to the CroMara Institute on Swinemünderstrasse, and Tucker Malarkey at the Dant Conclave. And to Tom and Constance Corlafsky, and the pleasures of their place. Much is owed to N. Lowry, his friendship, and his network of East London safe houses. Katharine Johnson never doubted I could do it. Heather Watkins let me use her truck-rumbled studio and gave me a squeaky chair, sharp pencils, and snacks in ramekins. Nicole Morantz said, “See. It wasn’t for nothing.” Dharma Nicotera and Andrew Land never let me down. Patrick Abbey came through in the end. Lola Oyibo cheered me on. My co-stroller MacGregor Campbell acted as conspiracy consultant. Big ups to my crim def advisors Celia and Ben. And mad props to Edward McBride, who showed me Burma, Beirut, and the Beqaa Valley.

At Fletcher & Company, Mink Choi boosted my spirits and prospects when she stood up early for this book and its author. Likewise, Rachel Crawford is a good woman to have in one’s corner. My editor at Mulholland Books, Joshua Kendall, saw within the early, teeming drafts of the novel what WTF was to become. I had to trust him and I am so damn glad that I did. My sincere thanks also to Wes Miller and Garrett McGrath. And to Pamela Brown, Carrie Neill, Andy LeCount, Ben Allen, Nicole Dewey, Heather Fain, Judy Clain, and Reagan Arthur. They are the village that this book took. I owe a serious debt to all the designers at Little, Brown and the cover artist at Faceout Studio; I think they nailed it. And I thank my stars that WTF had to go through copyeditor Tracy Roe before it got to you, dear reader.

Thanks also to Isaac Hall, from whom I learned about the examined life, the joys and perils of examination. And to Chris Hollern (RIP), who gave me this city. And to my sisters, ever behind me, and my mom and dad, who made me read and let me write.

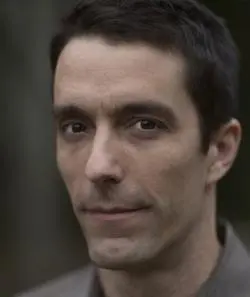

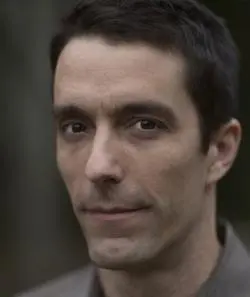

David Shafer is a graduate of Harvard and the Columbia Journalism School. He was born and raised in New York City. He has traveled widely, and has lived in Dublin and Buenos Aires. He has been a journalist, a carpenter, a taxi driver, and, briefly, a flack for an NGO. He now lives in Portland with his wife and daughter and son and dog.