Carlos pushed up from the porch floor, where he’d been sitting to the side of John’s wheelchair, leaning against the house, and went down the steps and across the yard and under the shadows of the tree’s branches at their edges. He reached the horse and the man perched upon it, and they saw the man’s face, his broad forehead and the shadows of his dark eyes, as he tilted his hat back and looked down at Carlos and spoke to him. They spoke for a while, and the horses and the donkeys were constant in their cropping, their heads moving aimlessly in infinite patience, as if they had all the time in the world. Then Carlos had turned and was heading back across the yard toward them, and in moments he was climbing the porch steps, and then he was speaking.

“I think he says if we want to know about ownership, or about the oil, we might want to come with him.”

Gino was sitting at the side of the porch steps, much as he’d sat at the window in the Manor, watching him, his back to them.

“What oil?” he said, his voice muffled in his throat. “Does he speak English?”

“No,” Carlos said. “And very little Spanish either. He says, under the tree, on the far side.”

Gino climbed up in his place, pulling himself by the railing, then limped down to the ground and started across the yard, his legs stiff, tugging and adjusting his clothing as he went. They saw the man in the saddle beyond him, maybe watching him, but they couldn’t tell.

“This is not in the plan,” Larry said, and Frank laughed, and John took a cigarette from his pack and tapped it against his can and lit it.

“I don’t know,” he said.

“Well, I do,” Frank said. “We don’t have one. But we didn’t come this far to do nothing. I didn’t. I feel pretty good this morning.”

“Shit,” Larry said. “So do I.”

“I think he says it’s a way. Two days, maybe three,” Carlos said.

“I don’t feel too bad either,” John said. “I think I can walk a bit. Maybe even ride.” Sparks fell to the blanket covering his knees, and he brushed them away absently.

They were sure about Gino and none of them needed to speak of him. But they were lying to one another, and Carlos could see that in the way they tested their bodies, then turned away from that, as they spoke. Pretty good meant waking alive once again each morning, not ready to ride out on horses into the wilderness. But they were watching the horses and the donkeys and the man, and Carlos saw Frank tug at the brim of his Stetson, much like a cowboy might on the plains watching cattle on a windy day. He saw John look over at Larry, who winked at him like a boy, then made a muscle in his thin biceps and pointed to it with a finger. His cap had slipped to a rakish angle, and his baggy, pajamalike pants were crossed at the ankles, seductively. He’d turned to face them, and was leaning against the porch railing, smiling, and John laughed and puffed at his cigarette. Then Gino was climbing the porch steps, his body loosened and almost supple again after his short walk. He lifted his black palm and showed it to them, the oil running in a line over his wrist and down his arm.

* * *

It took the rest of the morning and a good part of the early afternoon to get ready. Carlos insisted they eat lunch, and Larry wanted a bath, and the others thought that a good idea too, and Gino and Frank got fires going under the cauldrons, and Carlos and the man who’d come down out of the mountains worked at the pump and carried buckets. He was not really a man, but a boy of no more than seventeen, or eighteen, Carlos thought, but he couldn’t find words to ask the question. He was respectful of the men, treating them as equals, but attentive to their ages and infirmities. He carried the buckets to the cauldrons’ edges, but handed them over to be poured in, and he watched and didn’t help as Gino crawled under the house to hide away the bundles of gear they’d not be taking with them. They laid out efficient clothing, and Larry traded his cap for a water-shaped straw cowboy hat, fine and tightly woven, that the boy produced from a bundle on one of the donkeys. He was pure Indian, Carlos thought, and felt strangely comfortable in the presence of his stolid demeanor. Their eyes met from time to time, without expression, enigmatic to Carlos, but soothing. Frank helped John into a cauldron, then climbed into one himself. Larry sank in the other, his head resting in steam against the rim. Gino waited his turn, and Carlos and the boy too, after hand gestures and urging, took theirs. The old men watched the bodies of the younger men as they climbed in, then turned away from that useless yearning.

By three they were in their saddles and headed up into the foothills. The young man, his name sounded like Alma, was at the head, and Carlos brought up the rear, the donkeys tethered behind him, their line tied to his horn. It pressed against his leg when the donkeys tarried, but tugging it was familiar, some vaguely remembered gesture. He’d ridden when he was young, with his father. When he looked back, he could see John’s wheelchair strapped to a wooden frame. Larry road in front of him in his new cowboy hat, then Frank and John. Gino was lost to sight from time to time, but his broad sombrero marked him, where he bounced along behind Alma, and they’d barely climbed the initial incline and started up the next, when they heard him call out. “Are we almost there yet?” And Carlos heard John laugh up ahead, and saw him cast away the dead butt of his cigarette. The men had put folded blankets over their saddles, protection for their bony asses. Still Carlos saw their hips shift, their free hands working at their thighs, and saw Alma turn and look back when the horses broke into jarring trots, somehow knowing that, then slowing their procession down to a comfortable walk again.

The ground was desert sand, rocks and shifted slabs of shale, and they meandered, no pathway at all, and after each incline they reached a stretch of level ground, but with another incline just past that to negotiate, and they couldn’t see beyond it until they had climbed it and were confronted with another. Then they came to a rise that was a cliff’s face, an escarpment running up into the sky for a good hundred feet. They saw clouds above it and birds floating under them that may have been vultures or hawks, and Alma turned in his saddle and gestured to the right, and they headed along the escarpment, under its cool shadow, until they reached an arroyo that turned as they ascended, the horses slipping and kicking for purchase in loose shale, until the sun was blocked by a cliff face on their right as well, the air cooler, still, but growing bone-wearying.

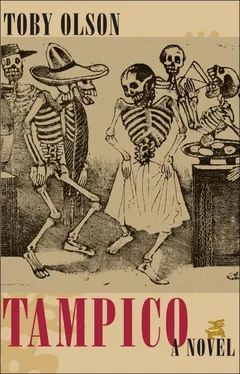

Carlos saw John struggle to get at the blanket tied to the saddle behind him. He managed to free it. Then it was over his shoulders, his hat brim touching it, and he looked like an old Indian. They came to a turning, and light broke out again ahead, the sun shimmering in blown sand at a distance above the escarpment’s lip, a dust devil in sun, as if an animate figure standing in the air, and nothing beyond it that they could see, until they got beyond it, pressing handkerchiefs and hats into their faces against the blown grit, and their procession had paused and turned and they looked back over the plains of the state of Tamaulipas, and could see the city of Tampico, parts of it between clouds that were now under them, and beyond it the Gulf of Mexico in the far distance. They heard a slap of leather, and Alma turned them, and they saw what lay before them.

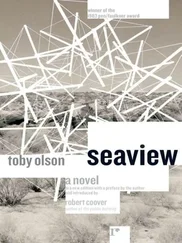

They were at the edge of a high plateau, the ground very much the same as what they had, in the last hours, passed over, stone, sand and shale, tufts of rough grass and low cactus poking up in places. The plateau seemed perfectly flat to the left and right, and ahead of them it was flat too, extending out for what seemed miles and only ending in the far distance where foothills began again, and above these foothills mountains rose, jagged and colorless, disappearing in mist and coming dusk at their upper reaches. They saw something in the distance, on the rough plain between themselves and the mountains, animals possibly, moving from left to right, but they were no more than tiny dots, blinking through cones of sand stirred up by capricious wind gusts.

Читать дальше