“I am fucking beat,” Frank said.

He sat on the steps near Gino’s knee, looking out to where Larry poked at the brush fire under the cauldron with a stick, still in his linen outfit. Steam was rising at the broad mouth, dissipating in the dusky air a few feet above it. Beyond the shadows of the oak’s branches and the ruined chicken coop, the foothills rose up darkly, then brightened into a golden glow where the sun bathed the last visible ridge. Larry was cutting carrots and celery now, and onions, casting them into the cauldron to join the three chickens. They’d brought a portable barbecue, and he’d settled it on a log and was using it as a table.

“I could use a little help,” he said, his voice like crystal in the clear evening air, and Gino pushed up stiffly from the porch steps and ambled out to the yard.

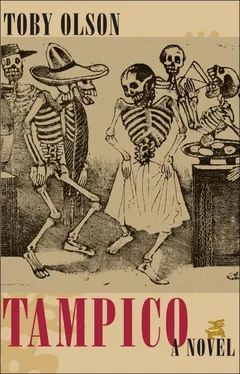

They’d eaten their dinner on the porch, watching the foothills darken and disappear, listening to the night birds singing above their quiet talk, no extended stories now, just light laughter and gentle joking in this new circumstance together. And they found ways to bring Carlos into it, for he had lived at the Manor too, for a while at least, just a few feet from the simple textures of their lives. They spoke of their few days in Tampico, the Panuco and the square, places John had taken them, to tell bits of his story once again. Carlos had nothing to add to all of this, but when they spoke of the lighthouse he joined in, telling his own story, that one about the fallen timber that had gotten him to the Manor. John spoke of Chepa, her house here, and the dogs dyed in the cauldrons, and Gino said he thought he’d tasted yellow in the chicken.

Carlos could hear their stertorous breathing through the crickets, the squeak of the bedsprings as they shifted, occasional groans. He started to think of the morning, though they’d not spoken of any plans, then he stopped doing that. This night, he thought, my house, but maybe it isn’t really mine, though I have the documents. He started to think of something else, the fire and his mother, but the crickets joined the breathing, indistinguishable from it, and he joined the old men in exhaustion and fell into a sleep that was empty of any concern.

This is his story.

Carlos awoke to the sound of activity, the screen’s slap at the rear of the house and a constant, monotonous clopping, and wondered if he could turn. He was wedged in on the veranda’s boards at the rail in his sleeping bag, and in his night’s turning had become a tightly wrapped mummy. He heard a hacking cough, somebody spitting and the shuffle of feet, and then rolled over, struggled to get his arms free, and found the zipper.

John was on the back porch in his wheelchair and straw hat, a bowl of steaming farina held in his cupped hands over the blanket that covered his legs, and he raised it in offering as Carlos passed Larry, who was tending the fire under another cauldron, one that had slipped from its stone foundation but would still hold water, and came up the porch steps. He’d walked over the baked clay at the house side, not wanting to disturb the men’s ablutions by entering.

“Sitting,” he said.

“Until I stand up,” said John. “There’s hot stuff inside.”

Gino was at the sink, ladling the cereal into bowls. They’d brought powdered milk and sugar, and there were spoons on the drain board. Frank was tidying his sleeping bag in a corner, and Carlos saw the two others, lined up side by side on the bed’s springs like body bags for skeletal remains.

“You found the toilet?”

“The shit house? Yeah. Such as it is. It’s tilted,” Gino said.

“Most everything is,” said Carlos, accepting the bowl Gino handed him.

When he reached the porch again, the chair was empty, and John was standing beside Frank at the railing. Both were rolling their shoulders, extending their arms and legs in odd gestures, as if ordering their bones again in their skins.

“We were just saying about the houses,” Larry spoke from his place at the cauldron.

There had been no buildings at all on the few-mile trek from the main road to the house, not when John had been here with Chepa, but they had passed many on their way out. They’d taken a bus from Tampico, then had managed to hook a ride in the bed of an old half-ton, a farmer returning from market.

“But the thing was, they were ruins. They’d been built after I left here, then had gone through a lifetime.”

“History,” Frank said. “Something else when it becomes real.”

“As with the bed,” John said. “It was very strange to be sleeping there again.”

“Especially with him.” It was Gino. He’d come out on the porch to join them, and Larry grinned at the cauldron’s side when he heard him speak.

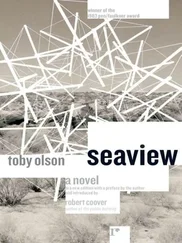

The sun rose over the house and lit up the foothills, low scrub and rock of various colors, and even the sand was various, darkly coarse in shadows the rock cast, subtle striations of color in the alluvial spills. There were flowers here and there, delicate desert bloom in reds and yellows, and a few patches of moss where rock under the surface held moisture.

John was speaking about the landing field, the bed, and the outhouse they could see from the porch off to the left near the ruined chicken coop, all parts of a story they had heard before, even bits of it remembered hazily in that past delirium by Carlos. But they were there now, and things were real and without anchor, and needed to be gathered again into a history. The oak tree stood at the edge of the yard and the story, massive and unconcerned. It seemed the machine of time, a perpetual calendar. It had been a sapling, and John spoke of its planting, and of Joaquín again, and the blood and the bullet holes in the house floor and the carvings of the names of revolutionaries in the walls. They’d made no plans for leaving, not just yet, and Gino shushed Frank when he wondered about things at the Manor.

They had turned toward each other, John in his chair again, Gino perched on the steps, Larry and Frank leaning against the porch rail, and were listening to Carlos tell bits of the tale explaining his arrival, mentioning Strickland and his manuscripts and death, Peter in his coma, his own days as a child in Tampico and later near the border. Then they heard Gino, a quick sucking of air whistling in his tracheotomy tube, and when they turned to him, he was pointing, a finger near his chin, and they all followed his gesture to the brink of the foothills just beyond the shadows cast by the oak’s branches and saw the man and the animals.

He sat the horse so comfortably in stillness, body slightly slouched and wrists crossed on the horn, that it seemed he might have been there all along and they’d not noticed him, but for the movements in the string of donkeys and the other horses, saddled and bridled, as they turned their lowered heads, pulling grass from the spare tufts, and lifted them to quietly blow and scent from time to time. He wore a hat, a sombrero with a brief brim, and most of his face was lost in shadow under it, but they could see his broad, flat nose, the slabs of his cheeks and his thick neck above the collar of his heavy cotton shirt, one stitched in rectangles in various patterns, the colors muted in reds and greens. The shirt matched his pants, in color and material, though the latter featured broad horizontal stripes of color, and his shoes at the ends of his short, thick legs were homespun too, something made of a dusty brown leather, loose-looking and comfortable, like sturdy slippers where they hung free of his stirrups. His horse’s head lurched up from the ground, catching something, and they saw his hand slip from the horn, a finger trace a vein in the animal’s shoulder where the saddle ended, and the horse quieted and went back to its cropping. There were five other horses, and three donkeys, their wooden racks loaded with blankets and cloth-wrapped bundles, and clay vessels were tethered to the wood with leather thongs.

Читать дальше