It was Boss Nunu who dragged him out of these personal reveries. “Do you play any recreational games?” he asked.

Ahmad looked at him, his expression that of someone who has just been jolted awake. “I don’t know anything about games,” he said.

Kamal Khalil laughed. “Our professor, Ahmad Rashid, is exactly the same,” he said. “You can chat to each other while we play a game for an hour or so.…”

“Come on, Muhammad,” he said turning to his son, “It’s time to go home.”

Ahmad’s heart gave a flutter. He looked at the boy once again and followed their progress as they made their way toward the door and then vanished from sight. Once again he asked himself in frustration how it was he could not remember where he had seen that boy before. By now the company had split up into separate groupings: Boss Nunu and Kamal Khalil were playing dominoes; Sulayman Ata and Sayyid Arif were playing backgammon; and Abbas Shifa had moved his chair so he could sit with the group around the café owner. Ahmad Rashid moved his chair to make room for the game players and came over to sit beside Ahmad Akif. The latter realized that he had come over, and that made the feelings he had just been having disappear, to be replaced once again by argument and conflict. Out went all notions of love, and in came anger and hatred.

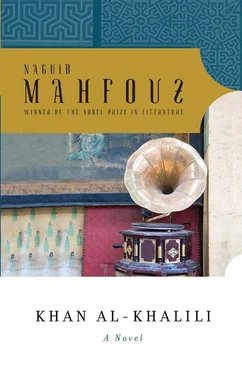

“How are you, sir?” Ahmad Rashid asked, turning in his direction. “By the way, I don’t want you to think that I’ve known Khan al-Khalili for a long time. I came here just two months before you.”

Ahmad was delighted that the other man wanted to befriend him. “Was it the air raids that made you move as well?” he asked.

“Pretty much. The fact is that our old house in Helwan was vacated for military reasons. I thought that a move into Cairo would mean I was much closer to work. I found it difficult to locate a vacant apartment until a friend happened to point me to this district.”

Ahmad Akif lowered his voice. “What an unsettling neighborhood it is!”

“You’re right. Even so, it has its consolations. It’s weird, but it’s also full of art and amazing examples of humanity. Just take a look at the café owner to whom Abbas Shifa is talking. Notice the drowsy look in his eyes. He takes a dose of opium every four hours. He goes about his work without ever really waking up; or, to put it another way, without ever wanting to wake up.”

“And does this improve life?”

“I don’t know. The only thing that’s certain is that he and others like him totally abhor the state of wakefulness that we enjoy and try to maintain by drinking tea and coffee. Were he to be compelled for some reason or other to remain in a wakeful state, you would find him yawning all the time, bleary-eyed, bad-tempered, and completely incapable of staying on an even keel until he found a way of canceling the world and floating in the universe of delusion. So is it some kind of nervous pleasure habitually obtained, or a purely illusory sense of happiness to which the human soul resorts as a way of escaping the hardships of reality? Only the café owner can provide the answers to that.”

Ahmad told himself that he too was scared of the hardships of reality, just like one of these drug addicts. He too ran away from it regularly in order to seek refuge in his isolation and his books. Was he any happier than they were? He felt an urge to explore the subject further.

“How can I concentrate on my studies,” he asked with a changed tone of voice, “with all this hubbub going on?”

“Why not? The noise is very loud, it’s true, but habit is that much stronger. You’ll get used to the noise, and eventually you’ll be disturbed if it’s not there. At first, I found it annoying and despaired of ever getting anything done, but now I can write my briefs and review legal materials in a completely calm and relaxed fashion amid this incessant din. Don’t you think that habit is a weapon with which we can face anything except fate itself?”

Ahmad nodded his head in agreement. Not wanting the other to outdo him, even with such a trite phrase, he said: “Here’s what the poet Ibn al-Mu’tazz has to say on the subject: ‘Adversity brings a sting of distress; should a man suffer it for a while, it lessens.’ ”

Ahmad Rashid gave another of his cryptic smiles. He never memorized poetry and hated hearing it cited. “So, Professor Akif,” he asked agreeably, “are you one of those people who are always citing poetry?”

“What’s your opinion about that?” Ahmad asked dubiously.

“Nothing at all. It’s just that I notice that people never cite modern poetry, only the old stuff. What that means is that, if they cite poetry a lot, it is always ancient poetry. I hate looking back into the past.”

“I don’t think I understand you.”

“What I’m trying to say is that I hate to hear poetry cited because I hate any resort to the past. I want to live in the present and for the future. When it comes to the provision of guidance and direction, I’m quite content to rely on the sages of this era.”

Unlike his colleague, Ahmad Akif was someone who believed that genuine greatness resided in the past. Or rather, the only examples of greatness that he was familiar with were in the past; he had no knowledge of greatness in the contemporary era. As a result, the other Ahmad’s statement made him angry again.

“Why would anyone wish to deny the greatness of times past,” he asked, “with their prophets and messengers?”

“Our era has messengers of its own!”

Ahmad was about to express his sense of outrage, but he didn’t want to express it in words unless it was his companion’s ignorance that was involved rather than his learning. “So,” he asked calmly, “who are the messengers of this era?”

“Let’s take those two geniuses: Sigmund Freud and Karl Marx.”

He felt as though a hand had grasped his neck and was throttling him. Indeed, he felt as if his honor had just suffered a deep wound, because he had never heard either of those two names before. He was now insanely angry with his companion, but was obviously unwilling to display his own ignorance. He shook his head as though he was well acquainted with the views of the two men.

“Do you really see them as being the equals of geniuses of the past?”

The young lawyer was thrilled to come across another educated person and was eager to argue points of principle. He pulled his chair up so close that they were almost touching.

“Freud’s philosophy concerning the individual,” he said in a low voice so no one else could hear, “has shown us the way out of the ills of our sexual existence that play such an essential role in our lives. Marx for his part has provided us with ways to liberate ourselves from the miseries of society. Isn’t that so?”

Ahmad Akif’s heart was pounding and his fury was barely suppressed. This time he did not know how to object, let alone to come out on top. All of which led him to dodge the whole issue.

“Take it easy, Professor,” he said gently, although his chest was bursting, “take it easy! In the old days we were all as enthusiastic as you are, but the passage of time and further thought on the matter both demand that we maintain a certain balance.”

“But I do think a great deal about the things I read!” protested Ahmad Rashid.

“I’m sure you do,” he replied, “but you’re still young. As you get older, you’ll acquire genuine wisdom. Haven’t you heard people say, ‘Someone one day older than you is a whole year wiser’?”

“Some ancient proverb, no doubt.”

“A sage one too!”

“There’s no wisdom in the past.”

“Oh yes, there is!”

“If there were any genuine wisdom in the past, it wouldn’t have become just our past.”

Читать дальше