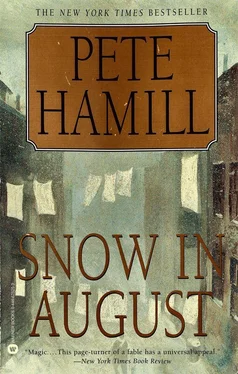

Pete Hamill - Snow in August

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Pete Hamill - Snow in August» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2009, ISBN: 2009, Издательство: Grand Central Publishing, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Snow in August

- Автор:

- Издательство:Grand Central Publishing

- Жанр:

- Год:2009

- ISBN:9780446569668

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Snow in August: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Snow in August»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Snow in August — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Snow in August», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“The monkeys built a boat, bigger than Noah’s Ark,” he said, “and they’d have eaten the king of England if it weren’t for the bloody bad weather. It was so cold, the lions and the elephants jumped in the water and swam back to lovely Africa, and Sticky had to sail home alone….”

His father took him to the dark movie palace the second time, after the war had started, and they sat in the vast balcony so Tommy Devlin could smoke, and together they watched They Died With Their Boots On . Errol Flynn played a soldier named Custer and the end was very sad. Michael had never before seen a movie where the hero died. He wanted to cry but didn’t, because his father didn’t cry, and he was sure his father would laugh at him for crying. On the way home, Tommy Devlin said he would take him to the Grandview again, when he came home, but he never did. That Monday, he went away to the army and never came back.

His mother took him one more time, when his father was in North Africa. She didn’t smoke, so they sat in the orchestra and saw a musical called The Gang’s All Here . But all through the movie, Michael kept thinking about his father. He wished he could go up the carpeted stairs, past the candy machines and the bathrooms and the entrances of the mezzanine, all the way to the balcony. He wished he could go up and down the aisles and find his father sitting alone. Smoking a cigarette. Wearing the blue suit and black polished shoes that were still in the closet at home. He wished he could hear his deep voice. He wished he could jump on his lap and hear him tell a story.

For a long time after that, and after they knew that Tommy Devlin was dead, he did not want to go to the Grandview. His mother never mentioned her dead husband when they talked about a movie at the Grandview. She just said it was “too dear.” Ninety cents to get in, while the Venus was only twelve cents on Saturdays and Sundays before five o’clock. Still, Michael longed for the Grandview the way he sometimes longed for his father. He passed it on long walks and gazed in at the murals; he studied the showcards in their glass cases, telling of coming attractions. John Garfield. Betty Grable. Humphrey Bogart. John Wayne. At the Venus, all the movies were old; they returned over and over again, the images ragged and often scratched. At the Grandview they came straight to Brooklyn from the movie houses of Manhattan. Now it might be different. No more Four Feathers! No more Frankenstein! Now he could see the new movies at the Grandview out of loyalty to his mother, even if there was a ghost in the balcony.

“Will we get in for free?” he asked.

“We’ll see about that,” she said, and chuckled. “First let me do the work.”

The deal was done. Three men arrived one Saturday morning and took away the coal stove, using hammers and chisels to separate it from the crusted cement foundations that kept it steady, pulling the stovepipe out of the wall and patching it with a circle of aluminum. Then they brought in the gas range: white, gleaming, with four jets on top, an oven, legs that looked like the legs of women, and even a clock. They connected it to the new gas line that ran up the side of the building, tested the jets and the oven, and then thumped down the stairs, leaving behind bits of broken iron, torn linoleum, drifts of coal dust, and a chisel. When the other tenants could afford to spend a hundred and thirty dollars for a gas range, they could be connected too. For the moment, the Devlins had the only one in the house, and it was free.

“Well,” Kate Devlin said, “let’s have a cup of tea. We can clean up the mess later.”

They divided the janitorial work. His mother changed the hall lightbulbs when they burned out and polished the brass mailboxes every other week. Together they rolled the battered metal garbage cans from the back of the hall to the sidewalk for pickup. They struggled with the much heavier ashcans, filled with ashes from the coal stoves that remained in the other apartments and from the coal-fired hot water boiler in the cellar. The other tenants came in to examine Kate Devlin’s wonderful gas stove, but they still used coal stoves for cooking and heat in the kitchens, while kerosene heaters warmed their living rooms. The women expressed envy and hope that they would have such a glory soon, if only their husbands would stop wasting money in Casement’s Bar, or if they could finally win the Irish Sweepstakes. Mr. Kerniss sent word that he would install central heating the following year — steam heat! — but would have to raise the rent to pay for the new boiler, the pipes, the radiators. For now, the coal stoves produced their many pounds of ashes. Since Michael was usually at school when the sanitation trucks came by on weekday mornings, his mother returned the empty cans to the back of the hall. Each evening before dinner, Michael would go to the cellar and shovel coal from the coalbin into the furnace, so that everyone in the building would have hot water. If there was snow, Michael shoveled the sidewalk and sprinkled ashes on the pathways so nobody would slip on the ice.

He worked hard at these chores, but one other task filled him with a kind of mindless joy: cleaning the halls. Every Saturday morning, after serving mass, after stopping at the synagogue on Kelly Street to turn on the lights, after greedily consuming buns and hot tea in the company of Rabbi Hirsch, he would race to Ellison Avenue. He would start at the roof door with a broom and sweep his way down four flights to the ground floor. He was always amazed at how much litter would be dropped in seven days: soda bottles, bunched newspaper, candy wrappers, pebbles, birdseed, dirt he could not name. Michael never saw anybody drop this stuff: that was the mystery; it just seemed to erupt and be there. But no matter where it came from, his job was to deal with it. On the ground floor, he would sweep the litter into a dustpan and drop it in a paper bag which he then shoved into a garbage can.

Then he would start again at the top with a mop and a bucket of hot water. When his mother first took the job, Mr. Kerniss bought them a new aluminum two-gallon bucket with a roller at the top and a great thick ropy mop. After Michael swept, his mother would descend the stairs splashing Westpine disinfectant from a bottle, and the pungent scent would fill Michael’s head as he moved behind her with the mop. Once the odor was so strong he had to turn away, gasping, and return to the apartment to wash his eyes with cold water and blow his nose. But he actually loved the smell: its clean, cutting odor erased the smells of food and stale beer, dead roaches and unwashed bodies.

And while Michael washed the hall, his mother was sweeping the apartment, straightening up, changing the bedsheets and pillowcases, washing underwear by hand in the sink, and all the while listening to Martin Block on the staticky old radio. Usually with the door open. Music made the work easier for Michael, smoother somehow, a pleasure , the mop moving to the rhythms of a dance band, his body bending and twisting, his skin beaded with sweat on the coldest days. The static didn’t matter. He hummed along with Benny Goodman and Glenn Miller, sang the words with Bing Crosby, Buddy Clark, and Frank Sinatra. It was like being in a movie, where people always had music in their lives. Music came from the other apartments too — opera music from Mr. Ventriglio, classical music from Mrs. Krauze — and sometimes Michael would wonder again what Jewish music sounded like, what songs the rabbi would sing when he was alone, what songs he had heard while dancing with his wife, long ago in Prague.

9

The rabbi was cleaning the stove, scrubbing hard with a rough cloth. While he did this, he murmured a litany of his jeweled new English words: stove, cleaning, teapot, cleanser, oven, range, jet, matches , with Michael occasionally correcting his accent. There were now scraps of paper Scotch-taped around the room, naming each object in English: door, table, sink, wall, bookcase , with the Yiddish word written underneath in English letters. Tir, tish, vashtish, vant, bikhershank . They were there for Michael. Occasionally the rabbi would stop in midsentence and point at a door and Michael would shout back: Tir! Or he’d touch the low ceiling and Michael would bark: Sofit! Their lessons were continuous and practical, with an undertone of magic; like magicians, they were showing each other that nothing was what it seemed to be, that one name for a thing might be hiding another name. A secret name.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Snow in August»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Snow in August» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Snow in August» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.