Des stood to go.

‘That’s what happens when you got a slag for an old lady. Every time you do the other, you find you full of rage . And what’s you next port of call? Prison. Well. Prison ain’t that bad. You know where you are in prison.’

‘And why’s that?’

‘All it is is, Des, when you in prison, you have you peace of mind. Because you not worried about getting arrested. That’s all it is.’

‘That’s all it is. Well I’m off.’

‘Yeah go on then. Before I think better of it. Go on, off with yer.’

‘I loved you, Uncle Li.’

Lionel’s right hand paused halfway to his mouth. ‘Mm. Well. I tried being loved. Thought I’d like it. Didn’t do a fucking thing for me … Give us a hug then. There there, Desi. There there, son.’

Des walked to the door, wiping his eyes with his sleeve.

‘Oy. Uh, out of interest. D’you give them they Tabasco?’

‘Yeah, I did. What you put in it?’

‘Oh you know. This and that. To keep them on they toes. That’s what I thought when I saw me Gazette . I thought, Des never give them they Tabasco! And them two little fairies went and slept right through it … Tell you what, Des. Just for a laugh I’ll give you ten million quid … No. I didn’t think so. Okay, I’ll give you this. You peace of mind. Go on, off with yer. On you cheap return. Go on … Bye-bye, son. Fare thee well.’

He took the child and strapped her to his chest. They left Avalon Tower. For him it had the solidity of an established fact: there was no longer anything to be afraid of. The air was oyster-grey, as night gave way to morning. Cilla drowsed .

At half past ten, when they returned, the dogs were gone. Quickly he washed her and changed her and gave her a warmed bottle, and they went out again. He had to have her on his chest and that seemed to mean that they had to go out again. Oh yes. There was also the irrelevant — the purely procedural — business of finding someone to come and change the locks .

Des knew that it would be very difficult to include the recent event in the world of things that existed. He kept trying; but he couldn’t fit it in. Later that day he took Cilla for a rendezvous with her mother in the staff car park at Diston General (Horace was still up there in death row on the seventh floor), and on the way he kept trying to fit it in .

She’s all flopsy. Oh, she’s all sleepy!

Yeah , he said . She stayed up too late. And what kept her awake, he now realised, was her sense of the wrongness of the dogs . She had a bad night. She had a bad dream.

All this existed: the variegated clutch of dressing-gowned smokers by the back entrance, the man crouched on the blue milk crate eating a bar of dark chocolate, the white vans, the coils of Dawn’s golden hair, the tawny tail of that hurrying cloud. Des was trying to make room in all this for the recent event, trying to make room in it for the baby’s bad dream. It would be very hard to do .

‘He went and had another drink in the morning,’ Mal MacManaman was saying as they approached the stairs. ‘Rang down for a bottle of Bénédictine. That’s what did for him, they reckon. He’d just finished it when he had his seizure in the car. His skin turned blue. They reckon he was an hour from death when they got him to Tongue. His brain was closing down. He was on eight breaths a minute. So they’ve given him an oxygen mask and a saline flush. And the dialysis for his kidneys. How’d you find him? You think he’s changed?’

Des was full of love for Mal MacManaman. But he just smiled and shook his head.

‘The bar bill at Rob Dunn Lodge —’ said Mal, round-eyed and slowly nodding, ‘they waived it. No one could believe it was true … You all right, family all right? Family all right? That’s the main thing.’

‘Thanks. Thanks. Mal, I’m so hungry.’

‘Well then. Now you got to go back in there.’

And with an inclination of his shoulders Mal MacManaman withdrew.

But something was finished, people were leaving, Lord Barcleigh and his learned friend were leaving, Sebastian Drinker was leaving, Jack Firth-Heatherington was leaving, and Raoul, too, was cruising from the room with a curved cellphone pressed to his jaw. Only the two women remained — the woman in the black-and-yellow business suit, the woman in the white veil. Des (who would soon be leaving) took a plate from the stack on the sideboard and began to fill it with green salad, tomato salad, ham, cheese, bread.

‘When he scragged them MILFs,’ ‘Threnody’ was saying into space, ‘he went and fucked my book. See?’

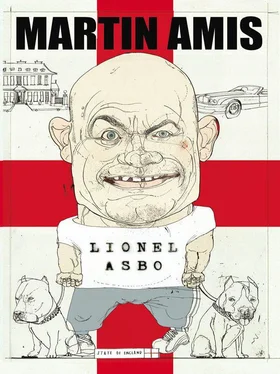

Des saw: her book was called Gentle Giant: The Lionel Sonnets . He saw also that the veiled woman had the darkly carbonated eyes of Gina Drago.

‘Gentle giant? Gentle giant, my arse . I’ve got to slag him off now, haven’t I. Got to say, you know, without my influence the shithead’s gone back to his old ways … What’ll you do, girl?’

Gina spoke. Des felt his flesh tremble when he heard her changed voice — the slurping lisp of her changed voice.

‘I suppose I’ll stay.’

‘Mm. While he’s inside you can get your face patched up. You’ll have long enough. Megan reckons he’ll be forty by the time he comes out … What’re you doing here, Wes? Come sniffing around for another couple of quid before he goes down?’

‘His name’s Desmond,’ said Gina as she stepped forward. ‘And he’s not like that.’

‘Gutsing himself before he sneaks away … Gentle giant. I–I made him loved . And now? Now? Danube’ll be pissing herself.’

Des knew that he had to leave, and quickly too. Gina’s veil had the near-transparency of misted glass, and he could make out the lineaments of her recentred face. It made him picture a tan balloon, roughly knotted by blunt male fingers. As in a dream, this image elided into another image — something far more terrible. He looked at the hunk of ham on his plate, with its pendulous lip of moist fat, and got to his feet.

‘I’m so sorry, Gina,’ he said as he kissed the gauzy tightness of her cheek.

And in the hall his raised voice was competing with the echoes as he cried out for Carmody.

… A towering honey-coloured carthorse with fringed hooves clopped soundlessly by on the grass verge, a little boy straddling it at an impossible altitude, as if halfway to the clouds. With spry jingles of the bell on her handlebars, a woman sped by in a crimson smock and a witchy black hat. On the scalloped surface of the millstream a green-headed, white-collared mallard led a flotilla of young, the busy ducklings weaving runic patterns in her wake. The air seemed to ripple with infant voices … Des assumed that this feeling would one day subside, this riven feeling, with its equal parts of panic and rapture. Not soon, though. The thing was that he considered it a perfectly logical response to being alive. He stopped at a grocer’s and bought three rosy apples. These would be eaten in just a little while.

For now he slipped down a lane and found a hedge to hide behind. For a full minute he stood on tiptoe, trying to elongate himself, trying to stay on top of it. But it was taller than he was, the pillar of poison was taller than he was, and up and out it came.

All right, no need to hurry — sit in the square and eat the apples. Take a later train. Dawn and Cilla were far away. Not long after midnight on Tuesday morning, Horace Sheringham gave his last groan, and they were down there in Cornwall laying him to rest in the family plot at his birthplace on Lizard Point — so there was plenty of time.

The image that had lifted Des from his chair in the dining hall at ‘Wormwood Scrubs’ was just an image, but it was an image of something real, something that existed or had once existed: a lunge pole, with the pink nudity of a plastic doll skewered on its pointed end …

Читать дальше