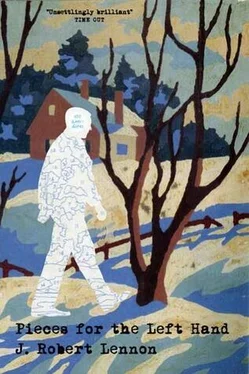

J. Robert Lennon

Pieces for the Left Hand: Stories

The author of these stories is forty-seven years old. He lives in a renovated farmhouse at the edge of a college town somewhere in New York State, with his wife, a professor at the college. He is unemployed, and satisfied to be unemployed, and spends an inordinate amount of time looking out the windows at the road and woods and the orchard at the bottom of his hill. He shaves once a week, is always showered before 8:00 a.m., and takes long walks daily, regardless of the weather. He cooks all the meals and does all the cleaning; indeed, he believes he is a better cleaner than the professional one he dismissed when he lost his job. He considers his solitude to be a great and unexpected gift to his life, and in fact occasionally finds himself regarding it with a kind of moral superiority, which he swiftly quashes, but not without a moment of amusement at his own vanity. The author is often amused by his faults.

What he did for a living isn’t important — if you were to talk with him for a hundred years, he would never even bring it up. It was the kind of job most people would call tedious, and so would the author, except that its particular tedium appealed to him, insofar as it busied his mind and protected it from worry. It supported his family when his wife was in graduate school, and now that it is gone, he doesn’t think about it at all.

Instead, he walks. Some days he walks for hours, cutting through fields and forests, hiking along the shoulders of roads. Local people, initially wary at his appearance, have grown used to it, and now they smile and wave when he passes. He enjoys imagining what they must think of him, this idle member of the middle class. He likes to think that they find him odd, though he is aware that there are too many people like him in this town for anyone to think that.

Some time ago, these walks began to shake things loose in the author’s mind. Dark memories of his childhood — his mother’s misery, his father’s death. He began to remember events he had witnessed, stories he had heard, thoughts he had had that he couldn’t let go. Things that happened to his neighbors, to his wife’s colleagues. Things he read in the paper. Every day, for many months, he sifted through the growing pile of memories, until he had begun to tell them to himself, as stories. I once knew a man, the stories began. A woman I know. In our town. The stories accumulated, forming a script in his mind, a repertoire. Some of them are true. Some have been embellished, or fabricated entirely. If he had to, the author could get up on stage and recite them all, but this isn’t the kind of thing it would occur to him to do, or that he would enjoy. What he enjoys is being alone, telling himself stories.

The stories are there now, in his mind, as he walks. He is happy with them the way they are: ephemeral, protean. In time his mind will move on to other things, and he will forget them, or most of them. Eventually the author will probably find a job — he isn’t bored, but he senses that he will be, and he would prefer not to taint with boredom these excellent days.

JRL

For more than a century, the main street in our town was named after a founding father of our state, a man who, in a recent revisionist essay, was revealed to have been a corrupt, bigoted philanderer who beat his children and disliked dogs. After a string of protests disrupted rush hour traffic, our mayor took down the street signs and promised to rename the street. But loyalists protested the removal, and the signs were restored. Further protests again eliminated the signs, and the battle has moved to the courts. Meanwhile, our town’s main street has no name at all, confusing visitors, complicating mail delivery, and making us the butt of vicious joking from other, less volatile neighboring towns.

It is not unusual in our area for a road to fall into disuse, if the farm or village that it serves should be abandoned. In these cases, the land may be taken over by the state for use as a conservation area, game preserve or other project, and the road may be paved, graveled or simply maintained for the sake of access to the land.

But should the state find no use for the land, the road will decay. Grass will appear in the tire ruts. Birds or wind may drop seeds, and tall trees grow; or a bramble may spring up and spread across the sunny space, attracting more birds and other animals.

In this case, the road will no longer be distinguishable from the surrounding land. It can then be classified as dead, and will be removed from maps.

Our town’s electorate, generally quite active in, even obsessed with, local politics, was silenced during this year’s mayoral race, in which the two prominent candidates, an incumbent Republican and a Democratic challenger, conducted campaigns of such a vituperative and vengeful nature that few city residents bothered to show up at the polls. Life might have gone on as usual afterward had not a nineteen-year-old college freshman, a hotel management major with no political experience, entered the race in the eleventh hour as an independent, registered six thousand students to vote, covered our town with cheaply xeroxed campaign posters reading STOP THE BULLSHIT, and published an editorial in the newspaper advocating the elimination of a city ordinance forbidding the sale of alcohol before noon on Sundays. The student’s victory was a landslide.

It all seemed like a good joke until I saw our former mayor, disheveled and dark-eyed, buying a six-pack of beer at a neighborhood grocery one Sunday morning. After that, my own failure to vote seemed a terrible mistake, and I was filled with a shame and dread that linger still.

When I was young, our quiet city suffered the most painful disaster of its history: fourteen teenagers fresh from a party secretly boarded a boat belonging to one of their parents, brought it out to the middle of the lake, became drunk aboard it and, in the sudden storm that followed, capsized and drowned. The subsequent public grieving, underage-drinking crackdown and lake-safety campaign were covered in our local paper with sensitivity and insight, by a reporter whose fine writing and acute perceptiveness of current events I had known when we attended high school together.

When recently three fishermen drowned in a similar boating accident, the same reporter covered the current event as skillfully and thoroughly as he had covered the previous one. I happened to encounter the reporter around this time, and commended him on his efforts, which commendation he seemed pleased to receive. But when I pointed out the parallels between this incident and the other, he grew puzzled and asked me which incident I meant. Surprised, I reminded him of the drowned teenagers, and at last he nodded in recognition.

I could not resist telling him that it seemed odd that he would not remember, while reporting on a boating accident, the worst boating accident in the history of our town, which he himself had reported on at the time. In reply he only laughed and said that the previous incident, tragic as it had been, was presently “off his radar.”

A local Indian tribe, irritated at the state’s reluctance to issue it a permit to open a gambling casino, dug deep into its historic archive and unearthed a long-forgotten treaty granting it a large parcel of land which consisted not only of the area generally recognized as their territory, but also of a small spur, bounded by and including two creeks, on which our beloved three-term Democratic senator happened to own a summer cabin. The tribe’s announcement of their intention to reclaim this land was met at first with puzzlement, then derision, as many state residents owned land there and enjoyed hunting, fishing, cross-country skiing and snowmobiling within its borders. Nevertheless, a respected state judge declared the treaty legal and binding, and in a terrific political victory for the tribe, the state reconsidered its permit refusal. Ground for the casino was soon broken, and tribal leaders made a verbal agreement not to act on their land claim.

Читать дальше