“Wow, it’s Kevin Lee! Right here in our lab!” Some good-natured chortling.

Huh?

Wentworth ventured some further explanations. “We’ve developed a technique for marking events so we don’t forget later. Whenever one of us goes out in public, we bring along a poster or sign indicating the date and time. That way, if we travel backward on Albertine in search of particular events, we aren’t thrown off or beguiled by unimportant days. And we bring clothing of various colors, red for an alert, green for an all clear. It’s a conspiracy of order, you understand, and that’s a particularly revolutionary conspiracy right now. What we’ve additionally found, by cataloguing memories — and we have guys who are medicated twenty-four hours a day thinking about all this — is that there are certain people who turn up over and over. We refer to people who are present at large numbers of essential Albertine nodal points as memory catalysts . Eduardo Cortez, for example, is a memory catalyst, and not in a good way. And there are some other very odd examples I could give you. A talk show host from ten or fifteen years ago seems to turn up quite a bit, perhaps just because his name is so memorable, Regis Philbin . You’d be surprised how close to the entire inner workings of the Albertine epidemic is Regis Philbin. When we’re around Philbin, we are always wearing red. We don’t know what he means yet, but we’re working on it. And then there’s you.”

“Me?”

One doctoral candidate, standing by the base of the telescope, nonchalant, spoke up. “If we had baseball cards of the players in the Albertine epidemic, you’d be collectible. You’d be the power-hitting shortstop.”

“We have a theory,” Wentworth said. “And the theory is that you’re important because you’re a writer.”

“Yeah, but I’m not even a very good writer. I’m barely published.”

Wentworth waved his plump hands.

“Doesn’t matter. We’ve been trying to find out for a while who originally came up with your assignment. It wasn’t your editor, Tara. That we know. She’s just another addict. It was someone above her, and if we can find out who it is, we think we’ll be close to finding a spot where the Frost Communications holding company connects to Cortez Enterprises. Somewhere up the chain, you were being groomed for this moment. Unless you are simply some kind of emblem for Albertine. That’s possible too, of course.”

Wentworth smiled, so that his tobacco pipe — stained teeth showed forth in the gloomy light. “Additionally, you’re a hero from the thick, roiling juices of the New York City melting pot. And that is very satisfying to us. You want to see? We know so much about you that it’s almost embarrassing. We even know what you like to eat and what kind of toothpaste you use. Don’t worry, we won’t put it on a billboard.”

Later, of course, the constituency of the Brooklyn Resistance was a matter of much speculation. There were women there too, with mournful expressions, as though they had come along with the Resistance though they had grave doubts about its masculine power structure. Women in modest skirts or slightly unflattering pantsuits, like Jesse Simons, the deconstructionist, who argued that doping the water supply was embracing the nomadic sign system of Albertine , which of course represented not some empirical astrophysical event but rather a symbolic reaction to the crisis of instability caused by American imperialism. And there were a couple of African Americanists, wearing hints of kinte cloth with their tweeds and corduroys. They argued for intervention in the economic imperatives that led to drug dealing among the inner-city poor. And there was the great postcolonialist writer Jean-Pierre Al-Sadir. He argued that the route to victory over civic chaos was infiltration of the Albertine cartels. However, Al-Sadir, because of his Algerian passport, had been mentioned as part of the conspiracy that detonated the New York City blast. Still, here he was, fighting with the patriots, if that’s what they were. It was a testament to the desperation of the moment that none of these academic stars would normally have agreed on anything, you know? I mean, these people hated one another. If you’d gone to a faculty meeting at Columbia three years ago, you would have seen Al-Sadir call Simons an arrogant narcissist in front of a college president. That kind of thing. But infighting was forgotten for now, as the Resistance began plotting its strategies. Even when I was hanging around with them, there would be the occasional argument about the semiotics of wearing red, or about whether time as a system was inherently phallogocentric, such that its present adumbrated shape was preferable as a representation of labial or vaginal narrative space.

“So you guys probably have one of those dials on a machine where we can go right to a direct year and day and hour and second, right?”

“Fat chance,” Wentworth said. “In fact, we have a room next door with a lot of cots in it—”

“A shooting gallery?”

“Just so. And we employ a lot of teaching assistants, keep them comfortable and intoxicated for a long time and see what happens. Whatever you might think, what we have here is a lot of affection for one another, so a lot of stories go around like lightning, a lot of conjecture, a lot of despair, a lot of elation, a lot of plans. You know? We see ourselves as junkies for history. Of which yours is one integral piece. Let’s go have a look, shall we?”

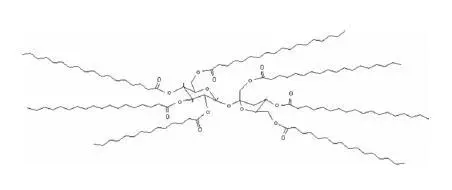

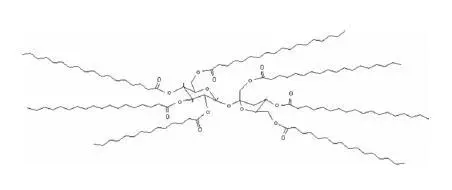

It would be great if I could report that the shooting gallery of the Resistance was significantly better than the Cortez shooting gallery, but really the only difference was that they sterilized the needles after each use and swabbed their track marks. No abscesses in this crowd. Otherwise, it was only marginally more inviting. Some of the most important academics of my time were lying on cots, drooling, fighting their way through the cultural noise of fifty years — television programming, B movies, pornography, newspaper advertisements — in order to get back to the origin of Albertine, bitch goddess , in order to untangle the mess she’d made. The other thing was that these guys were synthesizing their own batches of the stuff instead of buying it on the street, and when a bunch of chemists and biologists get into mixing up a drug, that drug chimes, let me tell you. They explained the chemical derivation to me too. Which looked kinda like this:

Apparently, the effect had to do with increasing oxygenated blood flow to neurotransmitters, thereby increasing electrical impulses. It wasn’t that hard to do at all. Miraculous that no one had done it before now. The only physiognomic problem with Albertine was her tendency to burn out the cells, like in diseases of senescence. Albertine was sort of the neurochemical equivalent of steroid abuse.

I was lucky. Jesse Simons volunteered to be the prefect for my trip, and she and Wentworth stood awkwardly in the center of the room as a grad student from the Renaissance Studies department pulled the rubber tie around my arm. It was the sweetest thing, tying off again. I didn’t care anymore about writing, I only cared about the part where I stunned myself with Albertine. I was dreaming of being ravished by her, overwhelmed by her instruction, where perception was a maelstrom of time past, present, and future. The eons were neon, they were like the old Times Square, of which it is said that the first time you ever saw it, you felt the rush of its hundreds of thousands of images, and I don’t mean the Disney version, I mean the version with hookers and street violence and raving crack fiends. Albertine was like a soup of NYC neon. She was a catalogue of demonic euphonies. I felt the rubber cord unsnap, heard a sigh beside me, felt Jesse’s arms around me, and the soft middle of sedentary Ernst Wentworth. Then we were rolling and tumbling in the thick of Albertine’s forest. I was back in the armory, and there was a bunch of bike messengers leading me out, and I was screaming to Tara, and to Bertrand, and to Bob, Save my notes, save my notes, and the bike messengers were beating on me, and I could feel the panic thing in my chest, I could feel it, and I said, Where are you taking me? I passed a little circle of residents of the armory, carrying home their government rations of mac and cheese, not a hair on the head of any of them, all the carcinogenic residents of the armory, all of them with appointments for chemo later in the week, and they were all wearing red . I heard a voice, like in a voice-over: We’re sorry that you are going to have to see this. It was better when you had forgotten all about it . And the bike messengers took me on a tour of Brooklyn in their Jeep, up and down the empty streets of my borough, kicking my ass the whole way, until my lips were split and bleeding, until my blackened eyes were swollen shut. We came to a halt down on the waterfront, on the piers. They dumped me out of the Jeep while it was still moving, and my last pair of jeans was shredded from all the broken glass and rubble. My knees and hips were gashed, but the syndicate wasn’t through with me yet; some more of Cortez’s flunkies took me inside a factory, a creepy institutional place, where they manufactured the drug .

Читать дальше