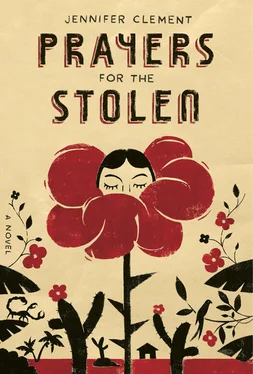

When my father left, my mother, who had never placed a lock on her mouth, said, That Son of a Bitch! Here we lose our men, we get AIDS from them, from their US whores, our daughters are stolen, our sons leave, but I love this country more than my own breath.

Then she said the word Mexico very slowly, and again, Mexico . It was as if she licked up the word off a plate.

Ever since I was a child my mother had told me to say a prayer for some thing. We always did. I had prayed for the clouds and pajamas. I had prayed for light bulbs and bees.

Don’t ever pray for love and health, Mother said. Or money. If God hears what you really want, He will not give it to you. Guaranteed.

When my father left my mother said, Get down on your knees and pray for spoons.

I only went to school until the end of primary. I was a boy most of that time. Our school was a little room down the hill. Some years teachers never showed up because they were scared to come to this part of the country. My mother said that any teacher who wanted to come here must be a drug trafficker or an idiot.

Nobody trusted anyone.

My mother said that every person was a drug dealer including the police, of course, the mayor, guaranteed, and even the damn president of the country was a narco.

My mother did not need to be asked questions, she asked them herself.

How do I know the president is a drug trafficker? she asked. He lets all the guns come in from the United States. Why doesn’t he put the army on the border and stop the guns, huh? And, anyway, what is a worse thing to hold in your hand: a plant, a marijuana plant, a poppy, or a gun? God made the plants but man made the guns.

My school friends were the friends I’ve always had. There were only nine of us in first grade. My closest friends were Paula, Estefani, and Maria. We went to school with our hair cut short and in boys’ clothes. All of us except for Maria.

Maria was born with a harelip and so her parents were not worried that she would be stolen.

When my mother talked about Maria she said, The harelip rabbit on the moon came down from the moon to our mountain.

Maria was also the only one of us who had a brother. His name was Miguel, but we called him Mike. He was four years older than Maria and everyone spoiled him because he was the only boy on our mountain.

Paula, as we all said, looked like Jennifer Lopez, but more beautiful.

Estefani had the blackest skin ever. In the state of Guerrero we are all very dark but she was like a piece of the night or a rare black iguana. Estefani was also tall and skinny and, since no one in Guerrero was tall, she stood out like the tallest tree in a wood. She saw things I never could see; even far-off things like cars coming down the highway. Once she saw a little black-red-and-white striped snake curled up in a tree. It turned out that it was a coral snake. These are snakes that want to drink the breast milk of sleeping mothers.

When you grow up in Guerrero you learn that anything that is red is dangerous and so we knew that snake was bad. Estefani said the snake had looked at her straight in the eye. She only told this to Paula, Maria, and me, just the three of us (her three best friends) because she knew it meant she was cursed. And she was, of course, as cursed as if the snake had been the evil fairy godmother with a wand who said your dreams will never come true.

When Maria was born with the harelip everyone was shocked. Her mother, Luz, kept her daughter inside the house and her father walked out the front door and never came back.

My mother liked to tell everyone what they should do. She did not mind her own business. So, she walked over to Maria’s house to take a good look at the baby. I only know this story because my mother told it to me many times over. She looked at little Maria lying in Luz’s arms covered by a white veil of gauze. She lifted the cloth and looked down at the baby.

She was born inside out, like an inside-out sweater. You just need to get her turned back around, Mother said. I’ll go and register her at the clinic.

My mother turned and walked down the mountain and took a bus to the clinic in Chilpancingo and registered the birth of Maria. This was done so that the local clinics would know which children in the rural area needed these kinds of operations. Doctors came from Mexico City every few years to operate for free but the patients had to be registered at birth.

It took eight years before a group of doctors came to Chilpancingo. A convoy of soldiers escorted them so that they would be protected from the drug traffickers’ violent confrontations. Of course, by this time, we were all used to Maria’s face. Because of this, some of her friends did not want her to have the operation. We wanted her to be happy and normal but her inside-out face made us fear the gods, made us aware of terrible punishments, made us think that something had gone wrong in our magic circle of people. She had become mythical like a drought or a flood. Maria was used as an example of God’s wrath. Could a doctor fix that wrath? we wondered. Maria inhabited her myth and even began to look as if she was made of stone.

We thought Maria was powerful. My mother never thought it was power.

She’s looking for an accident and she’s going to find one, Mother said.

Estefani, Paula, and I felt that the worst had already happened to Maria and so she was not afraid of anything, like the snake Estefani saw in the tree. It was Maria who picked up a long stick and poked at it until the snake fell to the ground. Estefani, Paula, and I shrieked and moved away, but Maria leaned over, picked it up, and held it between her thumb and index finger.

She looked at the snake and said, So you think you have an ugly face, well, look at my face!

Stop it, stop it, Paula said. It’s going to bite you!

Idiot, that’s what I want, Maria said and dropped the snake on the ground.

She called everyone an idiot. It was her favorite word.

One day when I was seven years old Maria and I were walking home together from school. Usually we all left school together and would meet our mothers down on the highway and then branch out toward our different houses. This time, I can’t remember why, Maria and I were alone. The school year was almost over and we were sad because the teacher who had come from Mexico City for a year was leaving and a new volunteer would be coming in September. In the countryside the people depended on volunteers from the city. We had volunteer teachers, social workers, doctors and nurses. They came as part of their required social work training. After a while we learned not to get too attached to these people who, as my mother said, come and go like salespeople with nothing to sell except the words you must .

I don’t like people who come from far-away, she said. They have no idea of who we are, telling us you must do this and you must do that and you must do this and you must do that. Do I go to the city and tell them the place stinks and ask them, Hey, where’s the grass and since when is the sky yellow? It’s all just like the damn Roman Empire.

I didn’t know what she meant by this, but I did know she’d been watching a documentary on the history of Rome.

I had that walk alone with Maria in the month of July. I remember the heat and the sadness of losing our teacher. It was very humid and my body wilted as we moved forward. It was so moist spiders could weave their webs in the very air and we had to walk wiping the webs and long, loose threads from our faces and hope no spider had fallen into our hair or down our blouses. It was the kind of humidity that made iguanas and lizards sleep with their eyes at half mast and even the insects were asleep. It was also the kind of heat that drove stray dogs down to the highways in search of water and their bloody carcasses marked the black asphalt from our mountain all the way to Acapulco.

Читать дальше