I placed my arm around Maria.

The ground here is so cold, she said.

Yes, in this place even the sun is cold.

As we sat on the cement in the meager sunlight, glass began to fall out of the sky. Glass dust fell from the stars.

Everyone in the yard looked up at the clouds.

There was silence.

The shards fell and children held out their hands and caught the dust. The crystal glittered. The ground and all surfaces were covered in glass snow.

The Popocatepetl volcano had dropped its cloud of ash on our prison.

One of the senior prison guards came out in the yard and announced to the visitors that they had to leave and told the prisoners they had to get inside. The volcanic ash was filled with microscopic shards that could cut up your lungs and eyes.

Maria and I stood up. Our dark hair had turned a gray white from the ash.

Did you know Paula had had a baby? It was McClane’s.

No.

Mike killed Paula’s child. I was with him that day. And he killed McClane.

Maria covered her mouth with her hand. This was a gesture she’d always made to hide her harelip. Even after the operation she continued to hide her broken face.

They’ll find us, she said behind the gate of her fingers.

Her body began to tremble.

I sat in Mike’s car, I said. I didn’t know. I wasn’t in there.

Did you see the girl?

I saw her dresses. Where’s my mother?

She’s here. She’s done the paperwork. You’re not eighteen. You can’t be here.

I’ll go to the juvenile jail for a year and then I’ll be back here. I’ve learned all about that. It’s how it works, Maria.

You’re out tomorrow. She didn’t want to see her baby in jail like a jungle bird, or like a wild parrot, in a cage. That’s what she said. Those words.

Where is she?

At the hotel. She told me to tell you that love is not a feeling. It’s a sacrifice.

Yes.

I’ll see you tomorrow.

Yes.

Stay in the shadows. Don’t get into trouble. Walk in the shadows.

Goodbye.

Here’s a bar of soap.

Can you give me something?

What?

Give me your earrings.

Maria was wearing a pair of plastic pearl studs. She did not ask what for, which I loved. She had always been like that. She never asked why. Maria assumed you knew what you were talking about.

Maria took off her earrings and dropped them in my hand.

See you tomorrow, she said.

Maria stood and I watched her as she walked through the crowd of robbers and killers to the exit.

She walked in the glass snow.

That night I gave Luna the earrings.

Thank you, Luna said. Do not try and rhyme, you know, understand, anything that happened to you here.

The Gods were angrier than we thought, my mother said.

These were the first words she spoke to me. She didn’t expect an answer.

Outside the jail I walked through a landscape where there were no trees or flowers. It was a terrain of discarded clothes as if the land had become cloth. I walked through the beige and blue fabric prisoners had stripped off their bodies and left behind in the street.

Volcanic ash still covered most surfaces and our steps left footprints in the glass powder.

My mother handed me a red sweater. I threw the worn sweatshirt Luna had given me on the ground where it became part of the blue-and-beige patchwork.

Outside the jail’s parking lot my mother had a taxi waiting for us. Maria was sitting inside. We got in the back seat beside her. I sat between them. Maria placed her arm around me.

To the South Station bus terminal, my mother said to the taxi driver.

Take off those flip-flops, my mother said.

She took a pair of tennis shoes out of her bag and reached down and pulled the flip-flops off my feet as if I were a little girl. Then she threw the flip-flops out the window as if they were candy wrappers.

Where are we going, Mama?

I’m going to wash all the dishes in the United States, my mother said.

We’re not going to wait around, Maria said. You have a meeting with the Social Services later today and they will probably place you in a juvenile delinquency center.

As soon as you turn eighteen, they place you right back in that jailbird birdhouse, my mother said.

I thought of Luna’s words about immigrants going to the United States. I could see my mother, Maria, and me swimming across the river.

Shit, think of The Sound of Music ! my mother said. It will be like that.

Yes, Maria said.

We’re going to the USA and I am going to wash dishes. I will wash all the dishes, all that steak blood and cake icing. You’re going to be a nanny to a family. You and Maria can be nannies. And we will never tell anyone where we came from.

Yes, Maria said.

Do you know why?

Why? I asked.

We’re not telling where we came from. It’s simple, my mother said. It’s simple because no one will ever ask.

Mama, I said, I have something for you. I stole something for you.

I opened my hand and took off the diamond ring and gave it to her. She looked at it without saying a word. She placed it on her finger.

You have made me love my hand, she said.

It’s beautiful, Maria said.

Someone cast a net across this country and we fell in it, my mother said.

As we drove through the city’s streets, through the traffic and diesel fumes of the large trucks, I watched my mother stare at the ring and pet the large diamond with her finger.

Along the avenue the street sweepers, with their mouths covered by handkerchiefs, were cleaning up the ash. They brushed it into large black plastic garbage bags. These bags were piled up like large boulders at every corner.

There’s something I need to tell you, I said. There are five people in this taxi.

I pointed to my belly.

There’s a baby in here, I said.

My mother didn’t blink or breathe or move and then she kissed my cheek. Maria kissed my other cheek.

They kissed me, but they did not kiss me.

They were already kissing my child.

My mother said, Just pray it’s a boy.

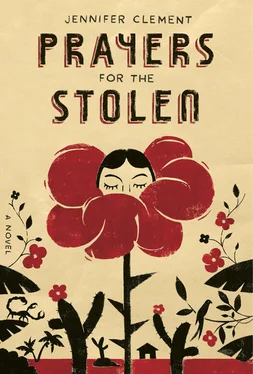

Prayers for the Stolen was written thanks to a National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) Fellowship in Fiction and the support of Mexico’s Sistema Nacional de Creadores de Arte (FONCA)