The Beard Scratchers nodded.

DJ Close-n-Play asked, “Is that a quote from Catcher in the Rye ?”

It was saxophonist Masayoshi Urabe’s opening statement from his Opprobrium magazine interview, but I didn’t want to get into “Who’s he?” and “What’s ‘opprobrium’ mean?” so I simply turned up the volume and said, “No, it’s my motto,” and went about naming my sources.

“That’s ‘Insider Tradin’ on My Mind’ by Penthouse Red,” I whispered, “from his Work Songs and Office Hollers of the Corporate Elite sampler.”

“Same cat who did ‘My Trophy Wife (Makes Me Feel Like a Loser)’?” asked DJ You Can Call Me Ray, et cetera.

“No, you’re thinking Greedy Steve McNeely.”

I went on.

“Audio Two’s ‘Top Billin’ ’ as rapped in the whistled language of the Nepalese Chepang.”

“I knew it!” Umbra said, pounding his forehead in musicolo-gist shame.

I continued my list: “Brando’s creaking leather jacket in The Wild One , a shopping cart tumbling down the concrete banks of the L.A. River, Mothers of Invention, a stone skimming across Diamond Lake, the flutter of Paul Newman’s eyelashes amplified ten thousand times, some smelly kid named Beck who was playing guitar in front of the Church of Scientology, early, early, early Ray Charles, Etta James, Sonic Youth, the Millennium Falcon going into hyperdrive, Foghorn Leghorn, Foghat, Melvin Tormé, aka ‘The Velvet Fog,’ Issa Bagayogo, the sizzle of an Al’s Sandwich Shop cheesesteak at the exact moment Ms. Tseng adds the onions. .”

Blaze raised his hand. “That’s enough,” he said. “You’re spoiling it. You’re explaining rainbows, motherfucker.”

He let the song play out, then continued. “You know what your beat reminds me of?”

“No,” I answered, rewinding the tape.

“It reminds me of the code of Hammurabi, the Declaration of DJ Independence, the Constitution, or some shit.”

Everyone else nodded in agreement, but I didn’t understand the comparison.

“Look, dude, you’ve sampled your life, mixed those sounds with a funk precedent, and established a sixteen-bar system of government for the entire rhythm nation. Set the DJ up as the executive, the legislative, and the judicial branches. I mean, after listening to your beat, anything I’ve heard on the pop radio in the last five years feels like a violation of my civil rights.”

We the true music lovers ofthe world, in order to form a more perfect groove . .

Don’t get me wrong, I appreciated Blaze’s praise, but I didn’t like my music being compared to a piece of paper and said so: “I think of it more as a timeless piece of art, you know, like the Mona Lisa of music. Your Constitution metaphor is too political. You’re making it seem like my music is propaganda.”

Pressing the play button, Blaze laughed, “Man, didn’t anybody ever tell you that all art is propaganda? It doesn’t matter whether you think it should be or it shouldn’t be, it just is, and motherfucker, like or not, you’re sitting on a funky Magna Carta. An unbelievably dope beat that’s this close to being the supreme law of the land — but as it stands now is no more than a musicalized Equal Rights Amendment, a brilliant and necessary idea doomed to the dustbin of change.”

The music quieted the room with a thumping irrefutability that was indeed just short of perfection. I turned it down.

“So what’s it missing?” I asked.

Blaze leaned back in his chair and smoothed his goatee. “Like any important document, it needs to be ratified.”

“Take my track to the thirteen original colonies and get people to vote on whether they like it or not?”

Elaine scratched at her jawline. “No, he’s just saying you need that one special somebody to approve it,” she said. “Think Mick Jagger ratifying Carly Simon’s ‘You’re So Vain.’ ”

Umbra contemplatively tugged on his soul patch and tossed out another example: “Charlie Christian ratifying Benny Good-man’s ‘A Smo-o-o-oth One.’ ”

So So Deaf stopped playing with his pointy imperial beard long enough to sign, “Like Kool G Rap on Marley Marl’s ‘The Symphony.’ “

“So who can ratify my beat?” I asked.

Blaze looked at me like I was stupid. “The Schwa,” he said, crossing his heart and blowing a kiss to the sky. “Who else?” The rest of us bowed our heads in reverence. Who else indeed.

Charles Stone, aka the Schwa, is a little-known avant-garde jazz musician we Westside DJs had nicknamed the Schwa because his sound, like the indeterminate vowel, is unstressed, upside-down, and backward. Indefinable, but you know it when you hear it. For us the Schwa is the ultimate break beat. The boom bip. The oo-ee oo ah ah ting tang walla walla bing bang . The om . He’s the part in Pagliacci where the fucking clown starts crying.

He had one minor hit record, a hard-bop rendition of “L’Internationale” that ironically charted briefly in the early stages of the Vietnam War. “L’Internationale” is on his seminal Polemics album. Polemics , recorded in 1964, is an engaging, thought-provoking, and shabbily produced masterpiece. Listening to that record is like sitting in on an impromptu graduate seminar taught by a favorite, slightly tipsy professor at the campus pub. Measure by measure the Schwa deconstructs nursery rhymes, advertising jingles, and the more sonorous of the world’s anthems. Each tune, from “Ten Little Indians” to “The Battle Hymn of Andorra” to the Slinky song, is lovingly turned inside out and played in a style so free it makes entropy jealous. Sandwiched between the Nazi Party’s “Horst Wessel Song” and Johnny Rebel’s swampbilly classic “Some Niggers Never Die (They Just Smell That Way),” “Do-Re-Mi,” the whitest song ever written, becomes more than simply a song I hate: The Schwa exposes that Alpine ditty for what it is, hate music.

But “L’Internationale” stands out. I’m the type who prefers to listen to one song a hundred times rather than a hundred different songs one time. And I listened to that song a thousand times straight, its majestic strains as quotidian to my day as breakfast cereal. It was a song that made me wish I’d come of age during the Spanish Civil War, shared a foxhole with George Orwell. It was a song that would’ve shamed Stalin and lionized Paul Robeson. In fact, I’m quite certain that if the song had gotten more radio play, America would’ve never stopped buying union.

Background information on the Schwa was scarce. I’d scoured the underground jazz magazines and reference books, and all I could find was a scant entry in The Jazz Encyclopedia:

Stone, Charles—b. 4/17/33, Los Angeles, California. A well-respected musician proficient in the improvisational techniques of the free-jazz movement of whom little is known.

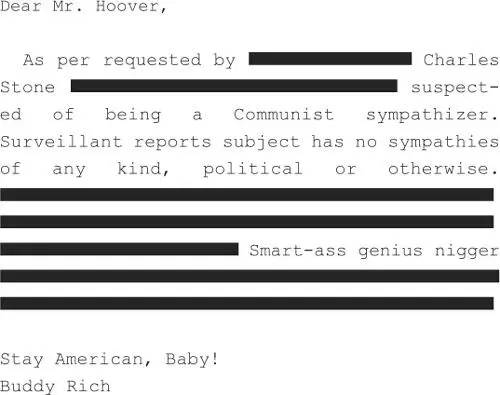

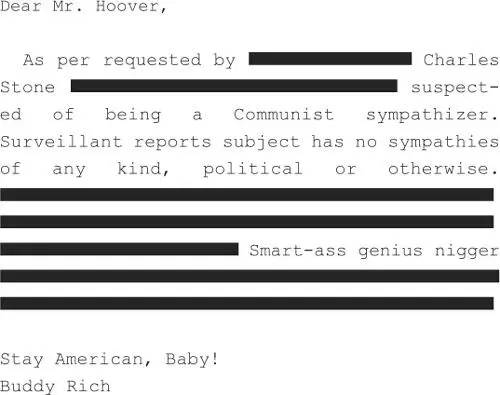

And a heavily redacted copy of a brief FBI file:

There were also scattered concert reviews from the early fifties that praised the “physicality of his performance.” It seemed the Schwa played with his body contorted in ghastly positions. Sometimes he stood onstage gyrating his pelvis or dislocating his shoulders for five minutes before producing any sounds. Most critics theorized that these corporeal contrivances were designed to illustrate that making music is more than a mental process, that a musician brings his body to a gig, not just his brain.

The Schwa’s discography was slight: three albums and a smattering of monaural EPs that had seeped into circulation. The most recent being Darker Side of the Moon , a foray into fusion that featured a cover photo of a black man’s backside and had the good fortune of being released at the same time as Pink Floyd’s multiplatinum Dark Side of the Moon . Due to clerical errors and acid-rock fans tweaked on microdots, the record did a steady if not brisk mail-order business. But since then the Schwa had completely disappeared from the scene, an act that served only to endear him to me all the more. There’s a special place in my heart for artists who inexplicably disappear at the top of their games. The list is a short one: Gigi Gryce, Louise Brooks, Rimbaud, D’Angelo, Francis Ford Coppola.* I admire these aesthetes for withdrawing into themselves knowing they have nothing further to say, and even less desire to hear what anyone has to say to them. That’s why I’ve never read Catcher in the Rye : I don’t want the novel to ruin a good reclusion.

Читать дальше