“That will be all,” the professor said. “Mr. West will be in the back to sign books. Please, just one to a customer.”

My uncle Poxl shuffled to the back. The professor whispered something in his ear as they walked to the signing table. The graduate student strolled leisurely out toward the back. He came close enough I might have reached out and ripped the earring from his smug punk ear, but as soon as violence rose in me — I was too young really to have done anything, and I don’t know even now what I could have done — he was already past. My parents and I didn’t need books signed; Uncle Poxl had promised copies. We stood to the side of the room as he signed. The line was so long ten minutes passed, then a half hour, and still readers and students stood with books. I was standing before the B ’s in the Used Fiction section. Right at eye-level was a green old dust jacket that read “Bellow— Herzog. ” A smell like dead cumin arose from the thing as its pages flapped freely in my hand. My father looked at me. I hadn’t even realized until after I’d done it that I was half-expecting a hundred-dollar bill to fall from it.

Every story my uncle Poxl told moved through me like radiation.

My mother said, “We could be here forever. I’m sure we’ll catch up with Poxl before he leaves town.” My father agreed, but he wanted to catch my uncle’s eye before we left.

Uncle Poxl was talking to a thin young man with blond hair cropped tight to his head, and a tweed jacket. When I looked down, I saw something in Uncle Poxl I’d never before seen: He sat with his shoulders hunched forward, his feet one on top of the other like they were trying to hide under his chair. He seemed not to be answering any of the questions he was being asked by this young man, but only wanted to move him along. Maybe he wanted to be done so he could come see us; maybe he was simply tired after a reading that had gone on longer than he’d intended, ended with a question he’d not expected amid the personal triumph of bringing his book to publication.

But where he’d shimmered like flag in a strong wind when he’d walked into the room, now he looked older, shaken, vaguely defeated. It was hard to reconcile it with the fame he’d just attained, the triumph of his narrative voice. We left without getting to talk to him. We never even got to congratulate him in person on his success.

Uncle Poxl didn’t come to call on us after his reading like he’d promised — my father said Poxl had left a message pleading for our leniency amid the chaos of his trip. He was off to New York and then the West Coast only four days later, and he hoped to visit Harvard, MIT, and Radcliffe before he left Boston. It sounded more like an invention than an actual excuse, but who could blame him with this new light shining upon him?

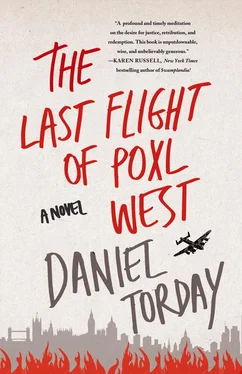

But this didn’t mean we would wait any longer before reading, finally, his book. On the kitchen table in front of my father, as he told us this story, was a thick plastic Waldenbooks bag. Inside were three hardcover copies of Skylock, one for each of us Goldsteins.

“We’ll have him sign them when he’s through with his tour, Elijah,” my father said. “But at least now we can read it.”

Uncle Poxl’s memoir was well over two hundred pages long. I read and read and read that first night after I got it, but my energy began to flag halfway through. I’d read more than enough to see that the stories as he had put them down were somehow fuller, more real and true than when he’d read them aloud from his manuscript pages. It’s no longer a surprise to me to find that first-person accounts are more evocative than the historiographies I teach, but at the time it was a revelation. My uncle Poxl’s stories now, between two covers, were so full of wandering detail, flashback, and of course, of the action that he’d recounted to us that night in Boston.

But more than that, they were typeset, printed, and bound. Somehow the permanence that binding his stories had received made them more believable, more important as I read them than they’d even been as he read them to me. As Poxl’s Tiger Moth pitched and rattled, as the ailerons on his Lancaster iced over and lightning struck his bomber mid-flight, the image doubled: In the front of my mind, sun glinted off the perspex of Uncle Poxl’s cockpit, drawn near-blindingly bright by adjectives and precise images. But in the back of my mind flashed only images of a youthful old man, lit from behind by some terrestrial sun, his hands gesticulating wildly around his head as he read to me from these same stories over a bowl of rapidly wilting whipped cream.

Though I had finished only half the book late the night after my father handed it to me, before I closed it I instinctively turned past the final pages, to the material that came after the narrative of the book had ended. There I found a list of those people my Uncle Poxl had wanted to acknowledge for their help in the production of his book, in bringing this life goal to fruition for him — the culmination of so many years of work. There were plenty of names there, but I didn’t let my eyes linger. Because I saw only one thing, standing out as if bolded and italicized — a lone tree in a forest — in a list toward the bottom half of the page:

“And thanks to Elijah Goldstein, my first reader and constant listener. I’ve told these stories to you, and for you.”

Poxl had noted me. There was my name, my full name, in print for the first time. When I published my first paper in an academic journal decades later, and every time since, it has felt simply a reiteration of that first moment I saw my name in Poxl’s book.

Would I be lying if I said seeing it was better than it would have been to be standing on stage at the Wang? To have a painting hung on the walls of the MFA? All those painters were long dead. My head felt lifted toward the ceiling by a sense of importance you might call ego — a sense that, if I’m honest, I’ve sought ever since without being sated, no matter how many journals accept my work. Spidery fingers ran up the back of my neck.

My reverie was broken when my mother called my name. The book clapped shut on my egotism. I yelled to my mother that I knew, I knew, and I turned out the light only to turn to dreams of my own grandeur mixed with my uncle’s.

I bragged of my uncle Poxl’s success for weeks after that night I got his book. The first weekend after, I read the second half, all in one sitting, a whole Saturday afternoon lost in Poxl’s European world. Now as I read, my energy didn’t flag. In the weeks that followed I read it over and over. Some days I came home and ran upstairs just to stare at the acknowledgments page again. I had been at work for months on a sententious poem, modeled on the Keats we’d just begun reading in English class, entitled “Upon Being Acknowledged.” It wasn’t quite an ode and it wasn’t quite a love poem, but it encapsulated all the self-seriousness and ardor of both.

Though I’d only read Poxl’s book, not lived his life, now I peppered conversation with both the language of the memoir—“Have you ever seen a nacelle?” I might ask a friend? “Do you even know what one is?”—and the broader life experience it implied. I’d only just kissed a girl for the first time at summer camp the year before, but now I felt I knew what it was like to have been with prostitutes in brothels in Rotterdam, to have fought in a war whose aims we now understood to have been wholly noble. I’d read and knew that there were mitigating factors, of course, the complicated relationships Poxl had been through, but somehow those passed between my fingers like water. I was reading for airplanes and heroism, and that’s what I found.

I told anyone I could all about Uncle Poxl’s accomplishments. The book received another glowing review in the daily Times the week after his Book Review triumph, and in the very same Boston Globe Poxl’s neighbor had written so many reviews for over the years. A week later it landed on the bestseller list. Not at the top of the list, but it was official: Poxl West was a bestselling author.

Читать дальше