We all gasped. This was a huge shock. I wondered if we were all part of some crazy

reality show called When Billionaires Pretend to be Human . I looked around for the cameras.

"Well, ever since I learned who really owned this outfit, I've been torn. I always wanted to give it back. But I wanted to keep it, too. I couldn't sleep some nights because I was so torn up by it."

Yep, even billionaires have DARK NIGHTS OF THE SOUL.

"And, well, I finally couldn't take it anymore. I packed up the outfit and headed for your reservation, here, to hand-deliver the outfit back to Grandmother Spirit. And I get here only to discover that she's passed on to the next world. It's just devastating."

We were all completely silent. This was the weirdest thing any of us had ever witnessed.

And we're Indians, so trust me, we've seen some really weird stuff.

"But I have the outfit here," Ted said. He opened up his suitcase and pulled out the outfit and held it up. It was fifty pounds, so he struggled with it. Anybody would have struggled with it.

"So if any of Grandmother Spirit's children are here, I'd love to return her outfit to them."

My mother stood and walked up to Ted.

"I'm Grandmother Spirit's only daughter," she said.

My mother's voice had gotten all formal. Indians are good at that. We'll be talking and laughing and carrying on like normal, and then, BOOM, we get all serious and sacred and start talking like some English royalty.

"Dearest daughter," Ted said. "I hereby return your stolen goods. I hope you forgive me for returning it too late."

"Well, there's nothing to forgive, Ted," my mother said. "Grandmother Spirit wasn't a powwow dancer."

Ted's mouth dropped open.

"Excuse me," he said.

"My mother loved going to powwows. But she never danced. She never owned a dance

outfit. This couldn't be hers."

Ted didn't say anything. He couldn't say anything.

"In fact, looking at the beads and design, this doesn't look Spokane at all. I don't recognize the work. Does anybody here recognize the beadwork?"

"No," everybody said.

"It looks more Sioux to me," my mother said. "Maybe Oglala. Maybe. I'm not an expert.

Your anthropologist wasn't much of an expert, either. He got this way wrong."

We all just sat there in silence as Ted mulled that over.

Then he packed his outfit back into the suitcase, hurried over to his waiting car, and sped away.

For about two minutes, we all sat quiet. Who knew what to say? And then my mother

started laughing.

And that set us all off.

Two thousands Indians laughed at the same time.

We kept laughing.

It was the most glorious noise I'd ever heard.

And I realized that, sure, Indians were drunk and sad and displaced and crazy and mean, but, dang, we knew how to laugh.

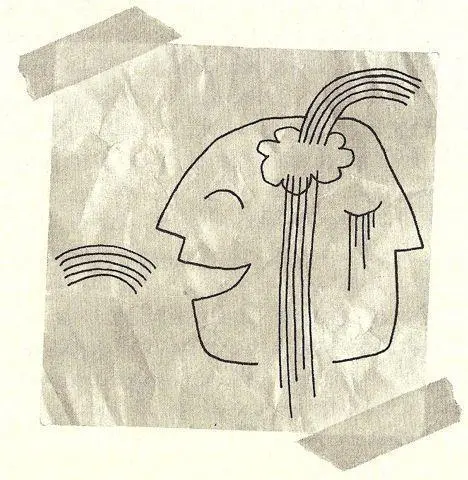

When it comes to death, we know that laughter and tears are pretty much the same thing.

And so, laughing and crying, we said good-bye to my grandmother. And when we said

good-bye to one grandmother, we said good-bye to all of them.

Each funeral was a funeral for all of us.

We lived and died together.

All of us laughed when they lowered my grandmother into the ground.

And all of us laughed when they covered her with dirt.

And all of us laughed as we walked and drove and rode our way back to our lonely,

lonely houses.

A few days after I gave Penelope a homemade Valentine (and she said she forgot it was

Valentine's Day), my dad's best friend, Eugene, was shot in the face in the parking lot of a 7-Eleven in Spokane.

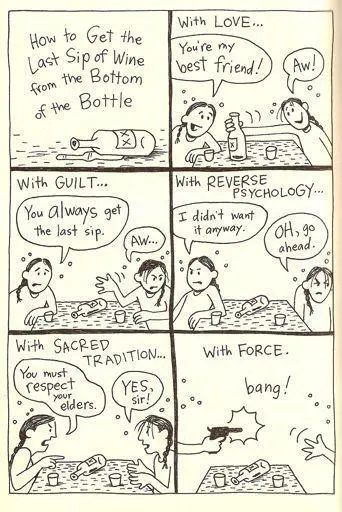

Way drunk, Eugene was shot and killed by one of his good friends, Bobby, who was too

drunk to even remember pulling the trigger.

The police think Eugene and Bobby fought over the last drink in a bottle of wine:

When Bobby was sober enough to realize what he'd done, he could only call Eugene's

name over and over, as if that would somehow bring him back.

A few weeks later, in jail, Bobby hung himself with a bed-sheet.

We didn't even have enough time to forgive him.

He punished himself for his sins.

My father went on a legendary drinking binge.

My mother went to church every single day.

It was all booze and God, booze and God, booze and God.

We'd lost my grandmother and Eugene. How much loss were we supposed to endure?

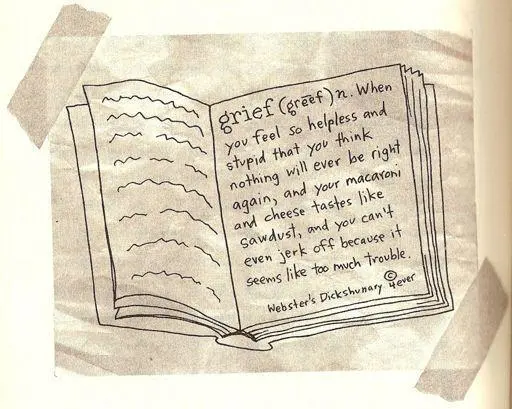

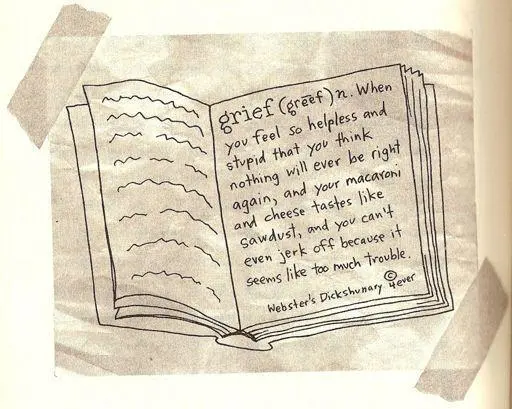

I felt helpless and stupid.

I needed books.

I wanted books.

And I drew and drew and drew cartoons.

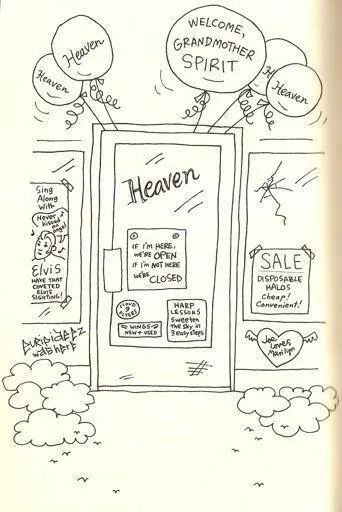

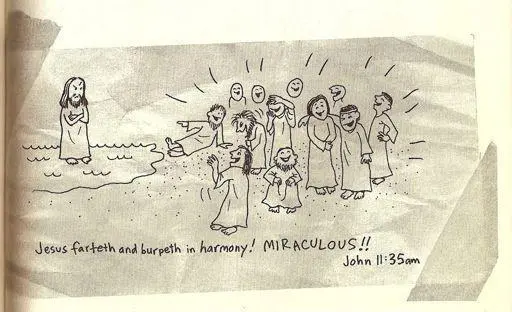

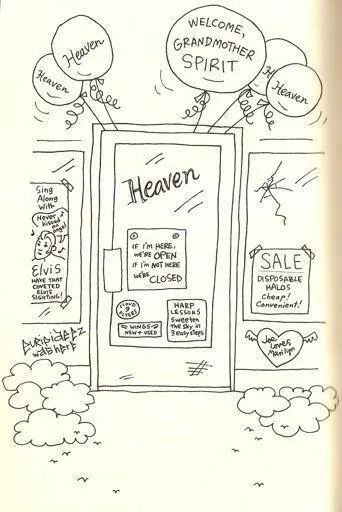

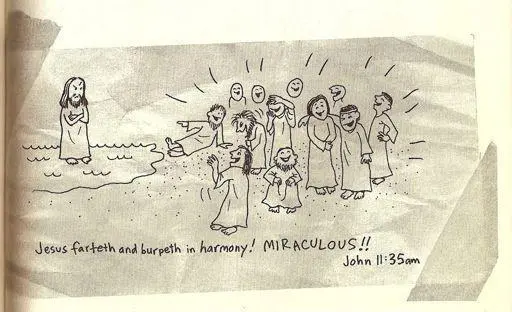

I was mad at God; I was mad at Jesus. They were mocking me, so I mocked them:

I hoped I could find more cartoons that would help me. And I hoped I could find stories that would help me.

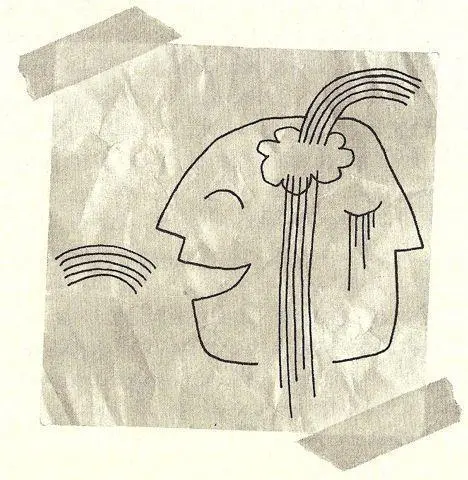

So I looked up the word "grief" in the dictionary.

I wanted to find out everything I could about grid I wanted to know why my family had

been given so much I grieve about.

And then I discovered the answer:

Okay, so it was Gordy who showed me a book written by the guy who knew the answer.

It was Euripides, this Greek writer from the fifth century BC.

A way-old dude.

In one of his plays, Medea says, "What greater grief than the loss of one's native land?"

I read that and thought, "Well, of course, man. We Indians have LOST EVERYTHING.

We lost our native land, we lost our languages, we lost our songs and dances. We lost each other.

We only know how to lose and be lost."

But it's more than that, too.

I mean, the thing is, Medea was so distraught by the world, arid felt so betrayed, that she murdered her own kids.

She thought the world was that joyless.

And, after Eugene's funeral, I agreed with her. I could have easily killed myself, killed my mother and father, killed the birds, killed the trees, and killed the oxygen in the air.

More than anything, I wanted to kill God.

I was joyless.

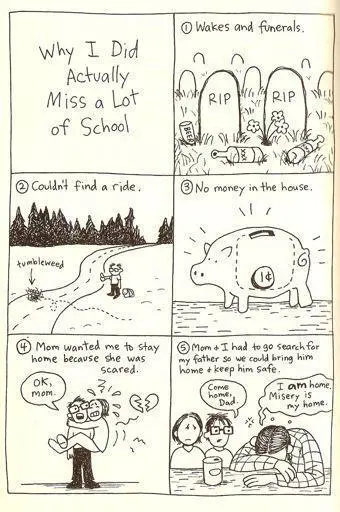

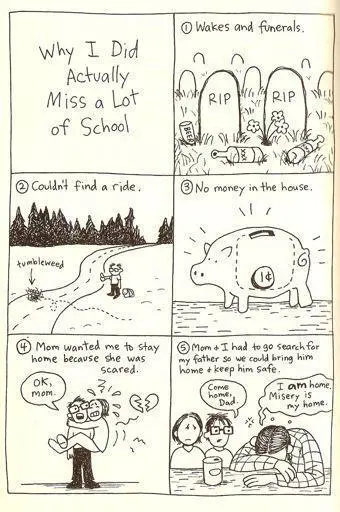

I mean, I can't even tell you how I found the strength to get up every morning. And yet, every morning, I did get up and go to school.

Well, no, that's not exactly true.

I was so depressed that I thought about dropping out of Reardan.

I thought about going back to Wellpinit.

I blamed myself for all of the deaths.

I had cursed my family. I had left the tribe, and had broken something inside all of us, and I was now being punished for that.

No, my family was being punished.

I was healthy and alive.

Then, after my fifteenth or twentieth missed day of school, I sat in my social studies

classroom with Mrs. Jeremy.

Mrs. Jeremy was an old bird who'd taught at Reardan for thirty-five years.

I slumped into her class and sat in the back of the room.

"Oh, class," she said. "We have a special guest today. It's Arnold Spirit. I didn't realize you still went to this school, Mr. Spirit."

Читать дальше