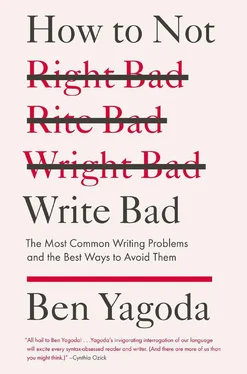

The nature of the fabulous fifty may be a little surprising; a lot of them don’t get much press. Even when they do try to address common writing errors, most writing guides and handbooks are off the mark, it seems to me. Often, they display a weird time lag. I remember being puzzled in junior high school to read in my grammar book that it’s incorrect to write of someone “setting” in a chair, rather than “sitting.” No one I knew in New Rochelle, New York, ever talked of “setting” in a chair. Only later, after becoming familiar with The Beverly Hillbillies and Ma and Pa Kettle films, did I realize that the reference was to a widespread rural locution of the forties and fifties.

Fast-forward to the second decade of the twenty-first century. The most (deservedly) popular writing guide is The Elements of Style , based on a pamphlet Will Strunk distributed to his Cornell students circa 1918. E. B. White updated it in 1959, and subsequent editions have made minimal changes. Rule 6 of Part I (“Elementary Rules of Usage”) is “Do not break sentences in two,” and the example given is, “I met them on a Cunard liner many years ago. Coming home from Liverpool to New York.” The trouble is not merely that almost everyone born after 1950 will be mystified by the phrase Cunard liner ; it is also that twenty-first-century American citizens almost never are guilty of this particular kind of sentence fragment. Don’t ask me why. They just aren’t. Another Strunk and White example of what not to do is this sentence: “Your dedicated whittler requires: a knife, a piece of wood, and a back porch.” Again, leave aside the sketchy cultural reference to dedicated whittlers. The problem here is that standards have changed such that a colon after anything but a complete sentence — the problem, to S. & W. — is now kosher. You might disagree with me on this, but you have to grant that to the extent it is a problem, it’s one that comes up extremely rarely. (The your + noun formulation—“Your dedicated whistler”—has pretty much gone by the boards as well.)

Then there are the more comprehensive writing books, such as The Bedford Handbook , which I have right in front of me and which qualifies for the final word in its title only if you have a really big hand. That is, it’s long—818 pages, plus index. It aims, as the second sentence in it says, to “answer most of the questions you are likely to ask as you plan, draft, and revise a piece of writing.” I’ll say. Pretty much everything is in here: common mistakes, uncommon mistakes, and lots of things that all people who grew up speaking English (and lots of nonnative speakers as well) know without giving them a second thought. Plus, it goes for $56.59 on amazon.com.

How to Not Write Bad has three parts. Part I gives and expands on a one-word answer to the challenge posed by the title, and goes on to talk more generally about what it means to be a not-bad writer. Parts II and III explain the most common writing problems and give examples I’ve taken from actual student assignments. Part III (to jump ahead for a second) deals with writing choices that aren’t strictly speaking wrong but are, well, ill-advised: awkwardness, wordiness, unfortunate word choice, bad rhythm, clichés, dullness, and the other most frequently committed crimes against good prose.

The mistakes in Part II are, literally, mistakes : of punctuation, spelling, wording, and grammar. There’s a lot of talk afoot about “grammatical errors,” so you might be surprised to find that grammar is the least of the problem, as I see it. Misspelled or just-plain-wrong words and train-wreck punctuation have gotten more prevalent over the years, for reasons I’ll get into later. And spelling and punctuation (more so than grammar) follow hard-and-fast rules, so there really is a clear sense of right and wrong.

As for grammar or syntax, linguists are fond of saying that a native speaker is incapable of making a grammatical mistake. Linguists are also fond of exaggerating, but they have a point, up to a point. No one born and raised in this country would say or write, He gave I the book , and to the extent that a book like The Bedford Handbook explains why the third word in that sentence should be me, it is wasting paper and ink and its readers’ time. In my experience, students are generally aware of and comfortable with grammatical standards. They tend to go off course in a relatively small number of areas (all of which are attended to in Part II). That would include: use of subjunctive ( If I was/were king ), pronoun choice ( He gave the books to John and I; Who/whom did you speak to? ), dangling modifiers ( Before coming to class today, my car broke down ), subject-verb agreement ( A group of seniors were/was chosen to receive awards ), and parallelism ( We ate sandwiches, coleslaw, and watched the concert ). *

Beyond these and a couple of others, most recurring grammar issues are fine points. That is, they are easily corrected or looked up and don’t have much bearing on writing or not writing badly. What’s more, accepted practice will probably change fairly soon so as to condone what the student has done. (Now, if you are not a native speaker or if you are don’t have some of the important rudiments of grammar, spelling, and so forth, you need something more basic than this book. The Bedford Handbook or a similar reference work would be a good place to start.)

On that idea of “accepted practice” changing, I recognize — as how could anyone not? — that standards evolve over time. There was a time when it was verboten to end a sentence with a preposition, start one with a conjunction, write an e-mail instead of an e-mail message , use hopefully to mean I hope that, and so on. Now all those things are okay. Going back even further, it used to be that the first-person future tense of to go was thought to be I shall go. If you said that today, you would get some seriously strange looks. Awful used to refer to the quality of filling one with, you guessed it, awe; now it means really bad.

But it takes time to change a standard. The mere fact that a substantial number of people do something doesn’t make it right. Take the title of this book. It splits an infinitive, which used to be wrong but isn’t anymore. It also says (for comic effect) Bad instead of Badly. That used to be wrong and still is. Same with something that an unaccountably large number of my students have taken to doing over the past few years; using a semicolon when they should use a colon, the way I just did. Still wrong. So is another strange and new predilection, spelling the past tense of the verb to lead as lead. I would guess it’s so popular because (A) spell-check says it’s okay and (B) people are misled by the spelling of two words that rhyme with led : the metal lead and the past-tense read . In any case, that semicolon use and that spelling may one day attain the acceptance of a split infinitive, but they haven’t yet. (Less than two hours after I wrote those words, I read a New York Times article with the words “what most troubled her was how he had mislead the public.” The change may come sooner than I think!)

Generally speaking, it’s fairly easy to figure out current standards. But a few things are trickier because they are right on the cusp of change. I make judgment calls on these. Probably the best current example is the use of they or their as a singular pronoun — in sentences like Anyone who wants to go to the concert should bring their money tomorrow or I like Taco Bell because they serve enchiladas that are oozing with cheese. The usage is almost completely prevalent in spoken English, in British written English (interestingly enough), in online publications, and, it almost goes without saying, in blogs and e-mails. I predict it will be accepted in American publishing within ten years. But it isn’t yet, and so for my purposes it counts as bad writing.

Читать дальше