With the links, users can move to other Web sites. That they want to consult.

In twenty years of teaching, I’ve never had something like that handed in to me. There are a dozen or more examples in the chapter, and the only one that rings slightly true is this:

Uncle Marlon drew out his tales. And embellished them.

The thing is, I don’t particularly mind the Uncle Marlon SF. Which leads me to a possibly useful generalization. (I hope you noticed that the previous sentence was a SF.) Sentence fragments can be acceptable and effective, in all but the most formal writing, if they come following a deliberate pause for effect. And if they’re used sparingly! (I can’t stop.) Reading aloud is especially important here. If you do, you’ll find that sometimes the pause is for humor (that talkative Marlon), sometimes for drama, sometimes for irony, and sometimes merely for emphasis.

So.

All that being said, an ill-conceived SF can be a really bad mistake. I do occasionally get them handed in to me. For example:

[ Of the students surveyed only 138 knew it was advised by the CDC to be tested for HIV annually when engaged in risky behavior. Classified as having multiple partners, unprotected relations, or regular work in risky medical fields ].

Of the students surveyed, only 138 knew the CDC advises annual HIV tests for people who engage in “risky behavior,” defined as having multiple partners or unprotected sexual relations, or working in risky medical fields.

If an SF is pointed out on a piece of your writing by a teacher, supervisor, or writer, I would advise you to eschew fragments for six months, during which time you’ll likely come to a better understanding of what a sentence is and isn’t. At that point, you can start playing around with SFs again. End of advice. And end of Part II.

*Sticklers will put a comma after the but in that sentence. See the next footnote.

*That’s not to say that sound is never a factor in comma use. In many situations, a comma is optional, and the rhythm of the sentence is an important factor in deciding whether to use one. For example, if a sentence-opening conjunction is followed by a parenthetical phrase, you may (but aren’t required to) use a comma after the conjunction. But, as far as vacations go, my whole family prefers the beach. In this case, it makes sense to choose based on whether you hear a pause after But.

*If you’re going for an old-fashioned, Henry James kind of thing, you can use a semicolon before an and, but, yet , or for .

Congress voted to fund twenty-seven pork-barrel projects this term; but the president had other things in mind.

*I haven’t been able to find a source to back me up on this, but I have always maintained that less should be used when the quantity is one, as in the song lyric “One less bell to answer.” I also insist that supermarket signs reading “Five items or less” are correct, since the phrase than that is understood at the end.

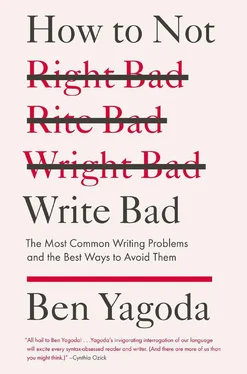

PART III.How to Not Write Bad

If you’ve absorbed the previous chapter, you’ve achieved — or are well on your way to achieving — the goal of removing the mistakes and errors from your writing. The next step is getting rid of a collection of qualities that aren’t technically wrong but are eminently undesirable. The best way to sum them up is with a simple chart:

Bad Not BadWordy or pretentious Concise, straightforward Vague Precise Awkward Graceful, fluid Ambiguous or misleading Clear Clichéd, hackneyed, or pat Fresh

That’s pretty much it. Of course, there are a lot of additional elements associated with writing well , or very well : brilliant similes and metaphors, masterful deploying of irony and other registers, humor, a personal voice, an ear for and ability to mimic other writers’ and speakers’ voices, a command of pacing and structure, the ability to construct long and complex sentences in the manner of Samuel Johnson, a sure and creative hand with metaphor and other figures of speech, a capacious vocabulary and the ability to use it, a sense of audience, an appreciation for subtlety, and so on.

But those are topics for another book. Writing not-bad is quite enough for this one. Before getting to the particulars, I’ll review the general approach to take. First, turn off the radio, the iPod, the television; put your phone on silence and in your pocket; X out of or minimize all screens other than the one you’re writing on. Multitasking = bad writing.

Second, know what you want to say. Any sort of uncertainty, fuzziness, or equivocation in your thoughts multiplies on the page and yields very bad writing. The boys in Entourage are always telling each other to “Hug it out”; my mantra for you is “Think it out.” You will often realize that you have to find out some more about your subject before you set words to paper. This is called research. Do it.

Third, be a mindful writer. A good homemaker doesn’t just fling silverware and plates on the table, but arranges them consciously and carefully. A stylish dresser chooses an outfit carefully. Be that kind of writer. Read each sentence aloud — literally, at first. Eventually you will develop an inner ear that will allow you to note the awkwardness, wordiness, word repetition, and vagueness that are the hallmarks of mindless, bad writing. And eventually, you will streamline the process and “hear” yourself write. And that is pretty cool.

A. Punctuation

1. QUOTATION MARKS

As a rule, stay away from using quotation marks except to indicate a title ( “Gone with the Wind” was Clark Gable’s greatest role ) or a quotation ( “Take me home,” she said ). Avoid, that is, the use of air quotes and scare quotes.

[ I have always considered him a “brother from another mother.” ]

[ My roommate thinks Lady Gaga is “the bomb.” ]

[ After a while, things got “hot and heavy.” ]

That is bad writing. My sense is that the quotes are the punctuational equivalent of a phrase like “just kidding” or “I’m just sayin’”—that is, a way to absolve yourself after using a cliché. People: a cliché is a cliché, whether or not it’s in quotes. There is no absolution. (See III.B.4.) Some of the time, you’re going to have to do the work of finding a fresh way to say what you mean.

Ever since we showed up on the first day of first grade wearing the same Star Wars T-shirt, there’s been this odd mystical bond between us.

However, if you really believe in the phrase, have the courage of your convictions (not “courage of your convictions”) and use it naked:

My roommate thinks Lady Gaga is the bomb.

After a while, things got hot and heavy.

2. EXCLAMATION POINTS, DASHES, SEMICOLONS, COLONS, PARENTHESES, ITALICS, AND RHETORICAL QUESTIONS…

…can all be effective if used correctly and in moderation. Common mistakes and misuses are addressed in Part II. The overuse issue is worth taking a couple of minutes with. When I was a magazine editor a few decades ago, I noticed that when some of the writers I worked with underlined or italicized a word for emphasis, sure as shooting, another underlined word or phrase would pop up within a couple of lines. And then another. I have continued to note this in published work, and have come to think of it as comparable to a phenomenon that occurs in concert halls: just as the sound of one person coughing makes other audience members powerless to resist the urge, so one use of italics can be contagious.

Читать дальше