There was no point in talking now. He should have known that from the moment in the bathroom, when she’d looked at him and wanted to laugh.

Back in the elevator of the hotel, his lips were tight with determination, like a priest with some difficult truth to impart. The girl beside him looked straight ahead at the sandalwood screen above the panel of buttons. She wore a striped cape and a headscarf and had a tattoo on her chin like a stylized trident. Everything was luridly bright, as if on display.

There were no more hooves in the walls. There was no more imaginary man behind him. In the hallway, there was the clarity of rectangular doorways and hotel carpeting beneath artificial light.

“Anita,” he said.

She rolled over in bed to see the two figures in the darkness. He switched on the lamp and stood in the yellow light, raising his chin, the necklace of teeth hanging from his neck. He was taking off his long velvet coat, shaking the hair out of his eyes, and she could feel the adrenaline coming off him like a wall.

“What’s going on?” she said.

“A little surprise.”

He gestured toward the girl, who was standing by the door, leaning her head on her shoulder like a sleepy child.

“Come on now,” he said. “Who do you think I am? Did you think I was just going to disappear? That I’m just some tosspot with no balls?”

He snapped his fingers and moved toward the bed. Then he grabbed her arm, just above the biceps. She jerked her body backward and fell sideways, clutching the pillows to her chest.

“Get up,” he said.

Diamond-shaped patterns of blue and red bloomed behind her eyes. She could feel the light in the room radiating into her skull like a sun. She dove for the foot of the bed, but he grabbed her by the ankle and she fell onto the floor. She put her hands over her face, covering her eyes, but he was on top of her then.

On the wall of the room next door, the Hindu gods Shiva and Kali were laughing beneath superimposed flames. It was the second time they had played the film, and no one was watching it anymore. They had ordered food that sat untouched on the dressers and the tables: couscous and ground lamb and a large pie made of phyllo dough covered in cinnamon and powdered sugar.

Green-faced Shiva brought his hands together in blessing, raising his joined fingertips to his lips, saluting the goddess Kali. Then there was an overlay of orange above a yellow Egyptian eye inside a triangle. Then the single word “End” appeared in gold letters on a saturated black background.

Brian was on the balcony, looking down at the pool, remembering a dream he’d had in the hospital in France. In the dream, he’d been walking through a kind of rice paddy, a pool full of tall green reeds that he pushed aside with the tips of his fingers. He had waded in up to his chest before he realized that there were hundreds of spotted deer on either side of him, almost submerged, raising their snouts just barely above the surface.

He could see now that she had been right all along and that none of it had had to matter. He had chosen to make it matter. He could see that clearly, now that it was over and she had no reason not to leave him.

When he came back inside, the girl was sitting on the bed, her hands clasped over her closed knees, looking at the mess of clothes on the floor without interest or intent. He lit a cigarette and it fell out of his mouth, then all the cigarettes came shaking out of the box and he picked the lit one off the floor and rose up out of his crouch with it smoking between his lips.

He saw the necklace on the floor, the beads and bits of mirror and human teeth. He saw his long blue coat with the fake ermine collar.

He sat down on the bed beside the girl and told her to lie down. Her legs were smooth and thin and gleamed as if they’d been rubbed in oil. He lay on top of her and closed his eyes and felt her face and lips against his throat. He held her like a limp thing in his arms and started coughing.

Anita was in the bathroom, holding a warm wet towel to her face, her chest heaving with some desolate mix of sobbing and mortified laughter. When she closed her eyes, green stars pulsed through her eyes back into her skull, where they swelled to a searing brightness. The pain ran from her shoulder up her neck, then twisted like a screw through the long ridge of her jaw. She sat on the floor and wiped the mucus from her nose. She was thinking that she couldn’t leave the bathroom, she couldn’t let them see her like this.

On the floor, The Sephiroth was still lying where she’d left it that afternoon. On the cover, the Eye of Horus gazed back at her with an almost gleeful indifference.

When he woke up, the girl was gone. There was a smell of sandalwood, of incense. There was a bar of light coming from between the curtains and on the nightstand was Anita’s glass half-filled with soda and limes. She wasn’t there. Her clothes and her suitcase were gone.

It was clear and warm that day. The patio in back of the hotel was a white glare, like light off glass, and the water in the pool was a bright, complicated green. There were only a few guests swimming or sipping drinks on the blue lounge chairs. Beneath the awning, on the patio, Tom Keylock sat by himself with a cup of tea. He was waiting for Brian, who wasn’t answering his door. Brian didn’t know yet that he was the only one who hadn’t checked out of the hotel.

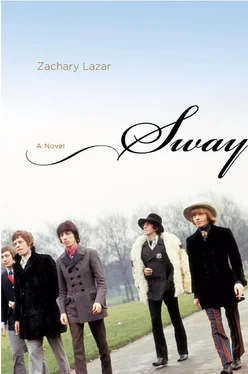

A short cab ride away, in the medina, the others were in the blue shop owned by the man named Hassan, filling in the last few hours before their flight home. They had just booked tickets that morning; they had left it to Keylock to break the news to Brian. Marianne was dancing to the Moroccan music on the radio now, her eyes closed, rolling her head, her long blond hair falling almost to her waist. Gold bangles slid down her forearms; the folds of her green sari loosened around her shoulders. She started spinning around faster and faster, unfolding her hands in the air. There was something defiant about how fast she was moving, a rebuke to the others for just sitting there, being calm. Hassan called out, clapping his hands. Robert Fraser started clapping too, raising himself erect. Mick brushed something off his sleeve, incredulous, then annoyed. He looked over at Anita and Keith in their corner, then back at Marianne, and something about her dancing reminded him of Brian: a helpless, unsuccessful gesture. She was the “Naked Girl Found Upstairs,” and she seemed to feel obliged to play out the role now.

Mick walked out the door, frowning, faking a cough. He saw a newspaper image of himself dancing on the set of a TV studio, his arms dangling from his shoulders like a scarecrow’s arms, a moment taken out of context and so made ridiculous. He didn’t know where to go now that he had separated himself from the group. He strolled with his hands in his pockets, lips set in a posture of grim appraisal, passing the row of whitewashed storefronts.

He had never liked Anita, had always thought she was poisonous, but now he had to come to terms with what she had done. He saw that in a way she had become the center of the band.

The walls of the buildings were pasted with hypersexual movie posters and Fanta orange soda ads in Arabic. He tried to imagine that he was amused by the teeming life before him — the men lugging broken stones in a wheelbarrow, the little barefoot boy in a wool shawl smoking a cigarette, the walls stenciled with black letters: DéFENSE D’AFFICHER.

When they got back to England, the band would either go on or it wouldn’t. Brian would either look after himself or he wouldn’t. He and Keith would either spend ten years in prison or they would make another record. When he was onstage, things went fast and he solved each problem in the same moment that it arose, building momentum, forgetting himself. But in ordinary life, even with the others around, there were times when there was nothing to say or do and everyone looked aimless and false.

Читать дальше