“Not if everyone’s going to be so solemn about it.”

Someone took their picture. Keith closed his eyes, nodding off slightly to the music. It was trancelike and insistent, a syncopated weave of oboes and violins backed by drums. Each note pointed to a shape without making it too obvious, each note a surprise but also a logical next step. It was like looking at a dark sky and gradually making out constellations in what had been a scrim of random stars.

Her hand felt embarrassingly alive in his. It was long and firm with a pair of rings beneath the first knuckle of her middle finger. He knew that the rings had nothing to do with him and that her hand in his meant nothing, but it made him not care about Brian, or about the band, or about the possibility of spending ten years in jail. It made him want to see what would happen. He kept noticing the faint, greenish bruise on the edge of her cheekbone.

Above the big open square called the Jemaa el Fna, the sun was starting to open up a gap in the mild cloud cover. It lit up the long folding counters of the food stands, where plates of raw ground lamb, diced tomatoes, olives, rice, sausages, and kebabs sat atop thick beds of wilting greens. Brian was just coming out of the darkness of the clothing souks with Tom Keylock when the light on the buildings changed from a muddy brown to a bright pink, all of it suffused with a saffron yellow that was like a second dawn in the middle of the afternoon.

“The acid’s starting to come on,” he said.

“Yes.”

“There’s that sort of humming you always feel in your teeth.”

“We have money. Cigarettes. Nothing can go too badly for us now.”

There was a persistent drone of horns. From the food stalls came the bitter smell of burning charcoal and the dry, organ-meat smell of grilled lamb. A thin man in chef’s whites and a toque was ladling a brown liqueur over a wide pan full of stone-colored snails.

“You knew, didn’t you?” said Brian.

“Knew what?” Keylock took him by the arm and guided him out of the way of a man walking by with a stack of crates on a dolly. Keylock was tall and round-shouldered with sideburns and horn-rimmed glasses. “It’s too much to talk about,” he said.

“It doesn’t matter,” said Brian. “I should have finished with that bitch a long time ago. It’s really starting to kick in, isn’t it?”

“Yes. We’ll just need to cool out for a while somewhere.”

There were three old men in brilliantly colored robes standing on the other side of the square. Their shoulders were slung with leather pouches and several strings of bells and brass cups. Their hats were like enormous tasseled lampshades woven from brightly colored yarn, reds and blues and yellows and greens.

“Perfect,” Brian said. “They’re brilliant, right?”

“Those men? Yes, fine, they’re brilliant.”

“I may take some more in a little while. I’d like to buy some of those hats. Or maybe just buy the men themselves, take them back to England.”

A man in a dark sport coat and a dingy woolen vest approached them, whispering something in French and fanning out some tattered business cards. Keylock brushed him aside with a rise of his chin. He turned to Brian, steadying him again with a hand placed lightly on his shoulder.

“Now you see what I was talking about,” he said, and suddenly each moment was so densely packed with situations that Brian couldn’t begin to take them all in. Bicycles and animals and carts moved in strange diagonals through the alleyways at the corners of the square. The sunlight gleamed on the hundreds of numbered plaques above the food tables, turning them into row after row of toylike moons. A group of men in white robes and turbans were dancing in a crowd, rattling a set of square metal tambourines in their hands. Translucent doves fled from the folds of their clothes.

When they got back to the hotel, they were all so high that each moment arrived in its own frame, like a set of projected slides — the revolving glass doors, the tiled lobby, the carved rosewood screens behind the fountain, the bellman in his white jacket and fez. The sun had come out, so they decided to spend the rest of the afternoon by the pool. Anita went upstairs to change, still feeling the bluster she always felt when she was with Keith. Walking back through the medina, he had been so stoned that he could hardly move his feet, his white fur coat slung over his back like a dead dog. Packs of boys had hovered around them, solemn and staring, only the youngest ones daring to come up close. One of them, about eight years old, followed them up a set of stone steps, his hands laced behind his back, as suspicious as an old man, mimicking every one of Keith’s clumsy movements as if learning the steps to a dance.

It was only when she got upstairs to the tenth floor and opened the door to her room that she remembered what was really happening that day. There were all the clothes scattered on the beds and the chairs and the tiled floor: Brian’s clothes and her clothes, all of them mixed together, just like at their flat in Earl’s Court.

In the bathroom, she picked up a book she’d been reading called The Sephiroth. She opened it at random to a page somewhere near the middle.

Speak to me of desire. Of the endless, coiling desire of the Self. Of how the Self, goaded by desire, becomes like an animal, compelled by need, caught in its sway. Now speak to me of the Soul, whom we see only in glimpses of others, in the blur of music, in the senselessness of dreams. Not who we are or what we believe, but the blinding shimmer from the void.

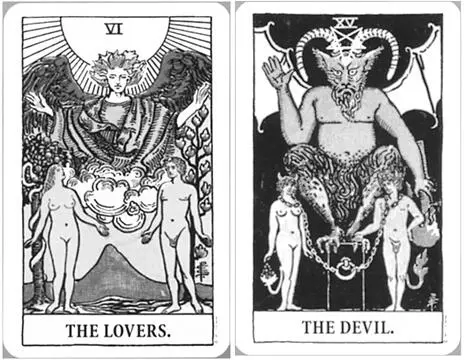

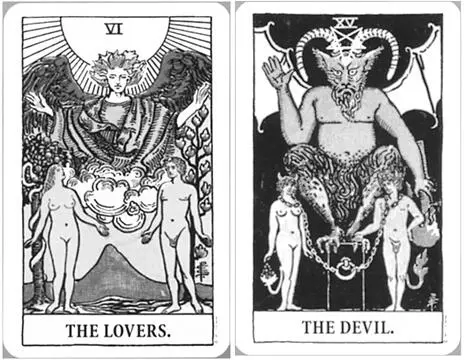

Figure 3. Trump XV, The Devil, Lucifer in his aged and corrupted form. As the Father of Fear, he has horns and batlike wings. Below him, two Lovers, Adam and Eve (Trump VI), are chained in darkness at his feet. Note how comfortable they appear in their chains, so loose around their wrists that they could free themselves at any time if they so desired.

KENNETH ANGER WAS WALKINGby the boardwalk on Coney Island one afternoon when he came across a group of boys working on their motorcycles. They were working-class kids, mostly Italian and Irish, their hair greased back in the manner of James Dean or Marlon Brando. From a distance at first, then closer, Anger watched them as they ratcheted and stared at their engines, their triceps shifting in the broken light, shaded by the boardwalk’s wooden planking.

He didn’t approach them that first day. Even on that hot afternoon, he was dressed entirely in black, except for a pale lime silk scarf around his neck. Surely the boys would see what he was, but then again what was he? The boys would never have guessed that a person like him would have tattoos on his forearms and wrists. A pentagram, an Eye of Horus, a scorpion — his rising sign, a sign associated with trickery and deceit. They would never have guessed that among other things, Anger thought of them as brothers in arms.

He was living in Brooklyn Heights now, penniless, sleeping on the roof of an apartment building in what could only be described as a shanty. It was a small metal shed without windows. Inside, he had a mattress and a kerosene lantern and an assortment of mugs. The shed and the apartment below it belonged to a film professor and his wife, Eliot and Beverly Gance, whose hatred for each other was like a cunning distraction from the doom that seemed to thicken the air around them: their sagging thoraxes, their nicotine breath, the haunted, midday fatigue that permeated their rooms. The Gances would start drinking on a Friday afternoon and not stop until Monday morning, during which time Anger would witness their brawls — broken dishes, humiliating sexual accusations, suicide threats, then a shoving match with drinks and cigarettes in hand along the raised brick edge of the roof where Anger had his shed. His presence seemed to reassure both of them into further flights of aggression. He didn’t have to pay the Gances rent, but he seemed to be paying them instead through a steady depletion of his own vitality.

Читать дальше